The Approach of the Royal Asiatic Society’s Anniversary

Often when I, Nancy Charley, write the blog post I include information of some anniversary – either commemorating the birth or death of a person who has been involved with the Royal Asiatic Society or whose work can be found within our Collections, or aligning with some commemoration that affects the wider community, such as International Women’s Day, International Tea Day or National Poetry Day. So last week, I wrote about William Alexander, the painter, as it was the anniversary of his death in 1816. However, in 2023 the Society has its own special anniversary. We will be celebrating 200 years since the Society was first established in 1823. As you might guess, there have been lots of discussions and preparations going on behind the scenes for some time now. And some parts of the celebration have already been shared within the blog, such as the new edition of James Tod’s Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan, a collaboration between the Royal Asiatic Society and Yale University Press, which is edited, and with a new introduction, by Dr. Norbert Peabody.

In the autumn of 2023, the Society will curate an exhibition to be held at the Brunei Gallery, SOAS, University of London. This creates an opportunity for us to present the life, work and collections of the Society, not only commemorating the story of the last 200 years but also celebrating the Society’s current activities and looking forward to a future of global networks and relevant research about Asia. The exhibition will also give us an opportunity to display many more of our Collections than we have capacity for on our premises. Therefore we are planning which collections visitors would enjoy and which would enable us best to tell the story of the Society and of the people who enriched the life of the Society through their interest and research in Asian studies. As part of the Collections team, I have been researching some of our early donations – the items that began our Collections. And here, I found a link with last week’s blogpost – the first donor was Sir George Thomas Staunton, the twelve year old boy who featured in William Alexander’s painting, The Approach of the Emperor of China to his Tent in Tartary to receive the British Ambassador.

By the time of the donation in March 1823, Staunton was 41 years old, and had amassed a large collection of books which he explained about in the letter he wrote to the Society’s Secretary, G.H. Noehden:

“Sir, Having in the course of my residence in China, formed a considerable collection of Chinese printed books, and also of manuscript dictionaries and other works of Europeans, calculated to assist the student in the acquisition of a knowledge of the language and literature of the Chinese, I feel confident that I cannot more effectually promote the object I had in view in making this collection, namely the more general acquaintance in this country with whatever may be found curious or useful among the productions of the Chinese press, than by a respectful offer of the collection to the Royal Asiatic Society.

“My wish is that it should be preserved entire, and placed in such a situation as may admit of its being at all times readily accessible to the British and other students of Chinese literature who may frequent this metropolis, under such regulations as the Royal Asiatic Society deem it expedient to prescribe.

“It is not in my power at present to offer to the Society an exact catalogue of the collection, but the enclosed memorandum will convey a general idea of its nature and extent.

“I have the honour to be, Sir,

“You most obedient, humble servant,

GEO. THO. STAUNTON.”

This letter is printed in full in an Appendix of Donations within the first Transactions of the Society and is followed by a list of books which covers eight pages – a considerable collection. Most were from China but some also covered India and Asia in general. As I read the letter, I felt that it, in its stilted nineteenth century language, Staunton expressed some of the motives for the Society – the mission statement as we would say in modern ‘speak’ – that of enabling anyone with an interest in Asian studies to be able to learn more. Of course, times have changed since the 1820s and access to information and education have altered far beyond anything Staunton could have envisaged. But still the Society, through its Journal, lectures, publications and collections, seeks to enable anyone interested in Asian studies to be able to meet others of a like-mind and learn more.

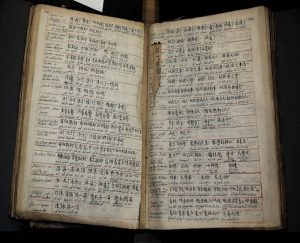

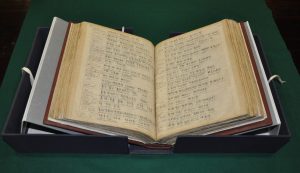

The Royal Asiatic Society’s Council, in the 1960s, decided that the books given by Staunton would best serve “British and other students of Chinese literature” by being donated to the University of Leeds who, at that time, was opening a new Department of Chinese Studies and needed publications for the use of their students. Therefore the majority of Staunton’s donation can now be found in the Brotherton Library at Leeds University. However we still have some of the manuscripts he donated at the time including a 1745 Latin-Chinese dictionary which was conserved in 2015 thanks to generous support from the National Manuscripts Conservation Trust and the Sino-British Fellowship Trust. Such conservation will mean that it will be able to be displayed in our exhibition.

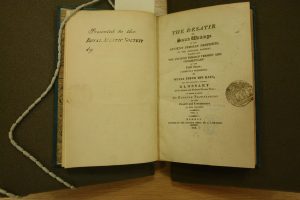

Staunton’s donation was shortly followed by others. The next person to add to the Society’s collections was William MacBean George Colebrooke (1787-1870), a distant cousin of the Society’s founder, Henry Thomas Colebrooke. In May 1823 he donated The Desatir or Sacred Writings of the Ancient Persian Prophets which had been published in Bombay in 2 volumes in 1818. This is now bound into one volume but still forms part of our collections.

William Colebrooke also donated some drawings of South Indian agricultural implements, the first artworks to become part of the Society’s possessions. These too, still form part of the Collection and also, possibly, would make suitable items for our exhibition as they are in good condition and have explanatory information with them. The list gives the names of each item but on the reverse of each drawing is a more detailed explanation.

We have many decisions to make concerning the exhibits but it is with anticipated joy at being able to share many of our treasures with a wider audience.