A Qurʾan manuscript with full Malay translation

We are pleased to introduce this week’s blog by Dr Annabel Teh Gallop, a member of RAS Council.

The Royal Asiatic Society holds a Qurʾan manuscript (Arabic 4), which is of exceptional importance as being the only known single-volume Qur’an with a full interlinear translation in Malay. The manuscript has just been fully digitised in honour of Professor Peter Riddell, in recognition of his pioneering work on the spread of Islam in Southeast Asia (Riddell 2001) and in particular on Malay commentaries on the Qur’an (Riddell 2017), and in conjunction with the publication of a Festschrift. The digitisation was sponsored by Annabel Teh Gallop, supported by the Merdeka Award 2022.

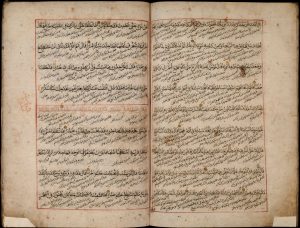

The manuscript is inscribed ‘Presented by Admiral C. M. Pole, Bart., June 19, 1830’. Sir Charles Moris Pole (1757–1830) served in the East Indies Station from 1773 to 1778, and it is most likely that the manuscript came into his possession during this early period. The first two folios have suffered severe damage, and in rebinding what remains of the first folio was reversed. Each subsequent page contains nine lines of Arabic text in a careful wide hand with the Malay text sloping beneath in a much smaller, very fine, hand. Text frames are of one or two ruled red ink lines; surah headings are in red ink and set in rectangular panels with red ink frames; and verses are separated with small gold roundels outlined in black. The laid paper is probably of Asian manufacture: hatched mold marks are visible but there are no visible chainlines or watermarks.

On the basis of a Malay commentary on the 18th sura of the Qur’an, Surat al-Kahf, in a manuscript from the Erpenius (d. 1624) collection held in Cambridge University Library, Peter Riddell traces a gradual chronological development, in both quantitative and qualitative aspects, in the field of Qurʾānic exegesis in Malay: “So by the middle of the 17th century, the Malay world was actively producing Qurʾān manuscripts, translations of certain verses, and at the very least exegesis at the level of the Surah.” The second half of the 17th century saw the composition in Aceh of the first full Malay commentary on the Qurʾan – the Tarjumān al-Mustafīd by ʿAbd al-Raʾūf – but the next major Malay work of Qurʾanic exegesis identified by Riddell does not appear for another 250 years, when the Tafsīr Nūr al-Iḥsān was published by Muhammad Said bin Umar of Kedah in 1925–1927.

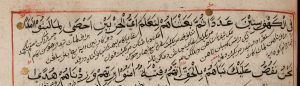

This framework is anchored firmly on evidence of “extended Qurʾan exegetical activity in Malay” (Riddell 2017: 48), but the question nevertheless arises as to how less “extended” efforts at Qurʾanic interpretation, in the form of the few known Qurʾan manuscripts with interlinear translations in Malay – which can certainly be dated to this long interregnum – might fit into this exegetical framework. Ervan Nurtawab (2020) has recently proposed that Qurʾan manuscripts with interlinear translations should certainly be regarded as tafsīr, as they were evidently created with the explicit intentions of explicating the meaning of the Qurʾān. This was explored in a study of two 18th-century Qurʾan manuscripts from Banten, in west Java, now held in the National Library of Indonesia (PNRI A.51 and W.277), both with exactly the same Malay translations, where Ervan identified elements of interpretation and presentation of variant views over and above the pure translation of the Arabic text, demonstrating the exegetical intent of the Malay texts, which were composed independently of ‘Abd al-Ra’uf’s work. A comparison with the RAS Qur’an shows that Arabic 4 contains almost exactly the same Malay translation as found in the two Banten Qurʾan copies. One example is shown below, of Surat al-Kahf verse 11 (in the text of Arabic 4, words not found in A.51 are underlined; lacunae compared to A.51 are indicated by * at the appropriate place).

Q.18:11: Then We drew (a veil) over their ears, for a number of years, in the Cave, (so that they heard not);

PNRI A.51: maka kami tutupi talinga marika itu supaya tiada didĕngĕr marika itu sawara dan kami kĕraskĕn atas marika itu tidur dalĕm guha itu babarapa tahun lamanya kata satĕngah adalah tidur marika itu dalĕmnya tiga ratus sambilan tahun lamanya maka tiap-tiap satahun dibalikkĕn < addition in the margin > marika itu supaya jangan dimakan tanah tatapi pada marika itu saparti siang hari jua.

RAS Arabic 4: maka kami tutup telinga mereka itu supaya tiada didengar mereka itu suatu suara dan kami keraskan atas mereka itu // tidur dalam guha itu berapa tahun lamanya kata setengah adalah tidur mereka itu dalamnya tiga ratus sembilan tahun * maka tiap2 setahun dibalikkan Allah mereka itu supaya jangan dimakan tanah tetapi pada mereka itu seperti siang hari juga.

Translation of RAS Arabic 4: Then We closed their ears so that they would not hear any sounds, and We deepened their sleep in the Cave, for a number of years; some say that their sleep lasted for 309 years, and every year Allah turned them over so that [their bodies] did not decay, but for them it was as if it was just the next morning.

It is thus highly likely that Arabic 4 originates from Banten, for not only are two of the only four other known Qurʾan copies with interlinear Malay translations (all in multiple volumes) from Banten, so too are three of the eleven known Qur’an manuscripts with Javanese translations, highlighting the association of Banten with this pedagogical tradition. The consistent use of gold verse markers is very rare in Southeast Asia, but notably has been recorded in two other Banten Qurʾans. Furthermore, the use of Asian paper, the unusual graphic layout, and the date of Admiral Pole’s Asian encounters, all support an early dating in the 18th century, at a time when the sultanate of Banten was flourishing as a centre for Islamic scholarship.

Further reading

This blog post was extracted from the following forthcoming chapter:

Annabel Teh Gallop, ‘Qur’an manuscripts from Southeast Asia in British collections’. Malay-Indonesian Islamic studies: a Festschrift in honor of Peter G. Riddell, ed. Majid Daneshgar and Ervan Nurtawab. Leiden: Brill, 2022.

Ervan Nurtawab, Qur’anic readings and Malay translations in 18th-century Banten Qur’ans A.51 and W.277. Indonesia and the Malay world, 2020, 48(141): 169-189.

Peter G. Riddell, Islam and the Malay-Indonesian world: transmission and responses. Singapore: Horizon, 2001.

Peter G. Riddell, Malay court religion, culture and language: interpreting the Qur’an in 17th century Aceh. Leiden: Brill, 2017.

Annabel Teh Gallop, The British Library

—

Bicentenary appeal

The Society is currently inviting sponsorship for new digitization projects to help celebrate its bicentenary in 2023. Further information is available here.

Readers may also wish to note that there is now less than a month to purchase the new edition of James Tod’s Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan at the discounted price. The prospectus for the reissue is available here. Fellows and friends of the Society are able to subscribe to the anniversary re-issue in advance of its publication for the discounted price of £725 (the standard list price will be £850). To qualify for the reduced price, full payment must be received by 16 December 2022. Subscribers will have their names published (if they so wish) in the List of Subscribers that will appear in the Companion Volume. Further information on how to subscribe and make payment can be found here.