Thomas Manning: a son’s letters to his father

With the accession of any new archive, decisions need to be made about how to arrange the papers ready to catalogue them. The Manning Archive arrived in 15 lots with some degree of coherence but these had been devised by the seller and do not represent any form of ‘original order’. We started by making a preliminary list of the items in each of the lots and putting all the papers into basic archival packaging. But where to start with more detailed listing and how to organise these papers? There are several forms of material within the collection – for example: correspondence, notebooks, notes, manuscripts and newspaper cuttings relating to all different parts of Manning’s life from childhood to old age. I decided to firstly work with the correspondence and to start by listing in some detail and numbering the letters between Thomas and his father, William Manning, rector of Diss. I have begun this list and already some discoveries of Manning’s character traits and interests are beginning to be revealed.

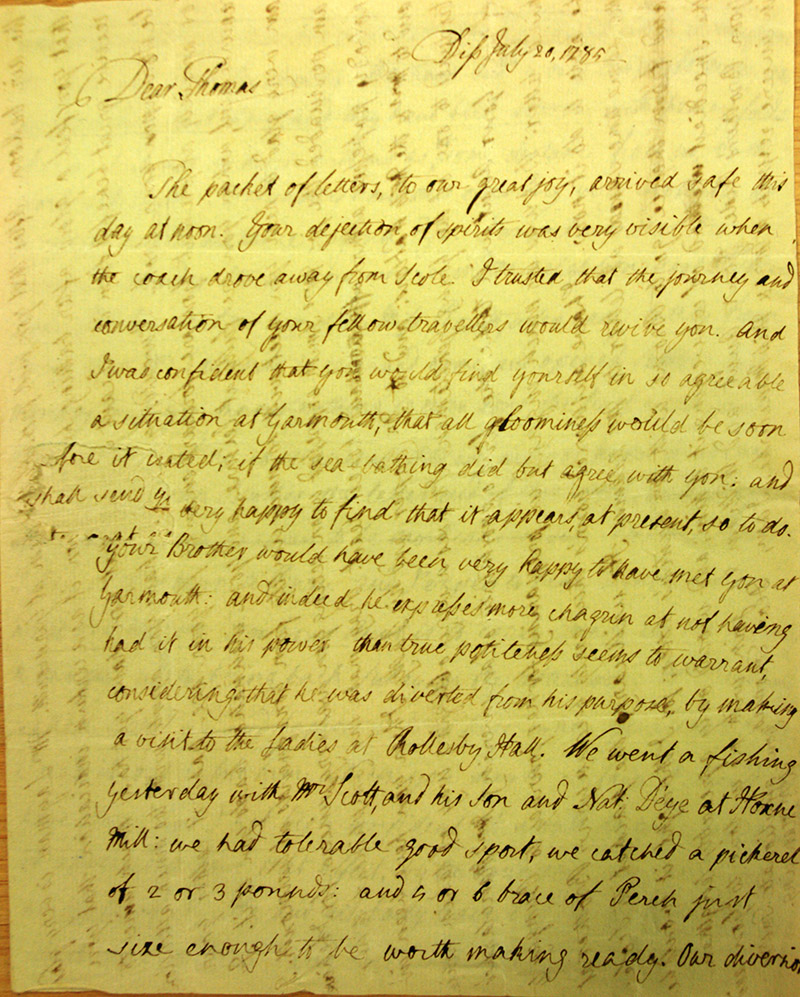

In 1785 we find William writing to teenage Thomas who has gone to Yarmouth for the sea-bathing. We have two newsy letters from his father. In the first he expresses his relief that Thomas is happy as he was concerned about his “dejection of spirits” when he had boarded the coach to go away. He sent news of going fishing and catching a pickerel of 2-3 pounds. In the second letter he writes of a trip to Bungay, and asks Thomas to go to stay with his aunt and uncle before returning home, so that his uncle may test the efficacy of the sea-bathing treatment

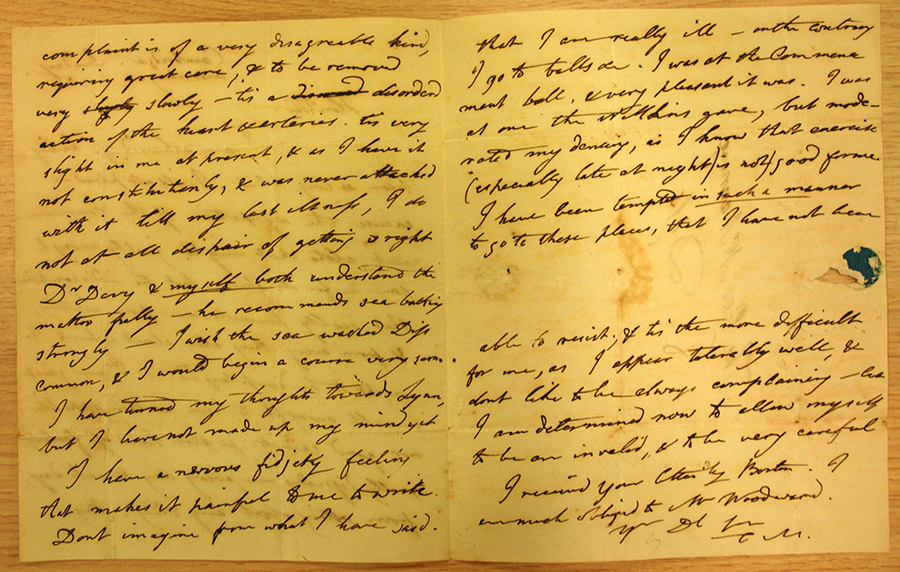

The first letter we have from Thomas to his father is from his time in Cambridge. It opens with what turns out to be a common theme running through his letters, “I am ashamed of having been so long silent…” He then writes how he has been ill – “I am just unwell enough to have neither appetite nor good spirits, & that kind of feeling generally dissuades me, every day & each day, from setting about anything”. He continues, “I have a nervous fidgety feeling that makes it painful to write”. But in true student style, “Don’t imagine from what I have said that I am really ill – on the contrary I go to the balls etc…. but moderated my dancing as I know that exercise (especially late at night) is not good for me.” This letter does not really give us any indication of the adventurer to come.

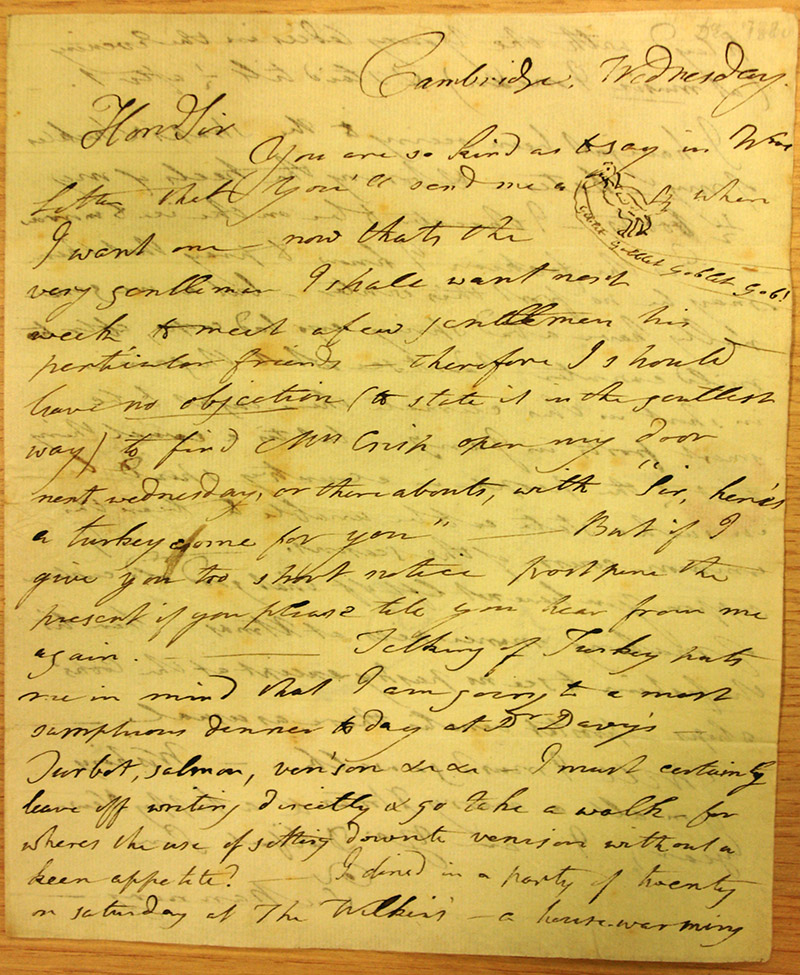

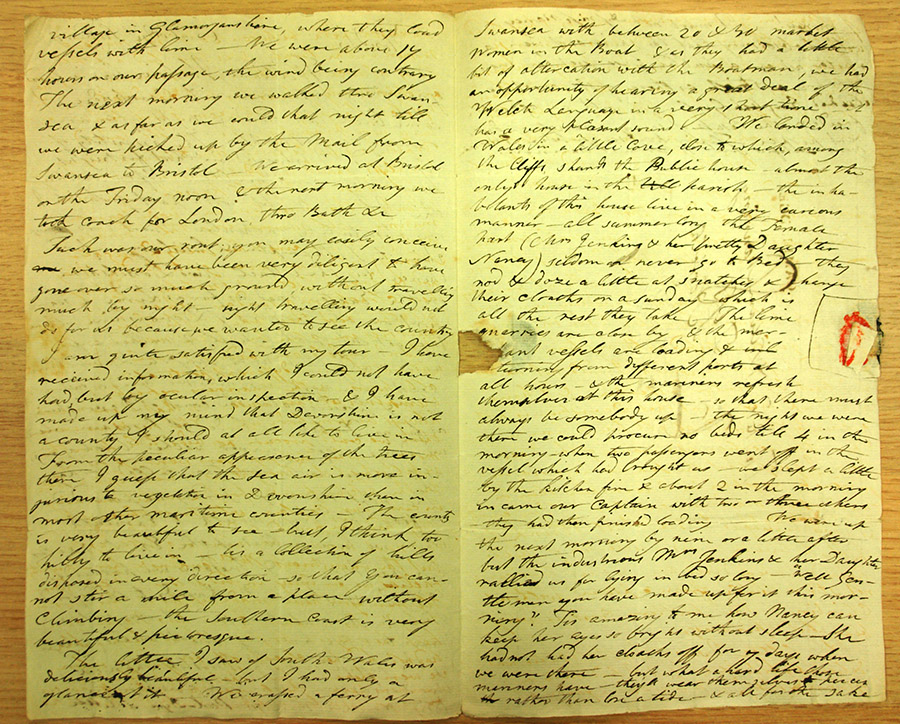

We have several letters from Thomas to his father from his time in Cambridge or whilst visiting Cambridge friends. In one he thanks his father for a gift of a turkey ready for Christmas, whilst in 1801 his letters show that he had been touring the country with a friend who was looking to buy a piece of land. Thomas states that he would not like to live in Devonshire because “from the peculiar appearance of the trees there I guess that the air is more injurious to vegetation”.

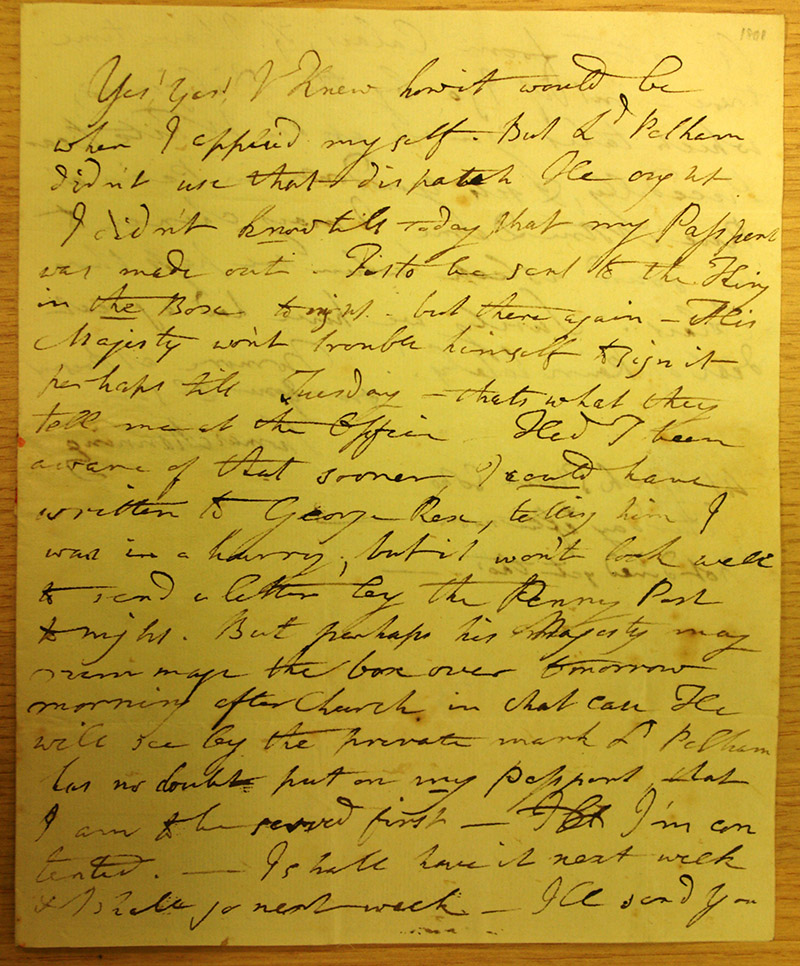

In December 1801, Thomas is in London impatiently waiting for his passport so that he can travel to France. He writes: “I didn’t know till today that my Passport was made out. Has to be sent to the King in the Box tonight, but there again – His Majesty probably won’t trouble himself to sign perhaps till Tuesday – that’s what they tell me at the Office. Had I been aware of that sooner I could have written to George Rex, telling him I was in a hurry; but it won’t look well to send a letter by the Penny Post”.

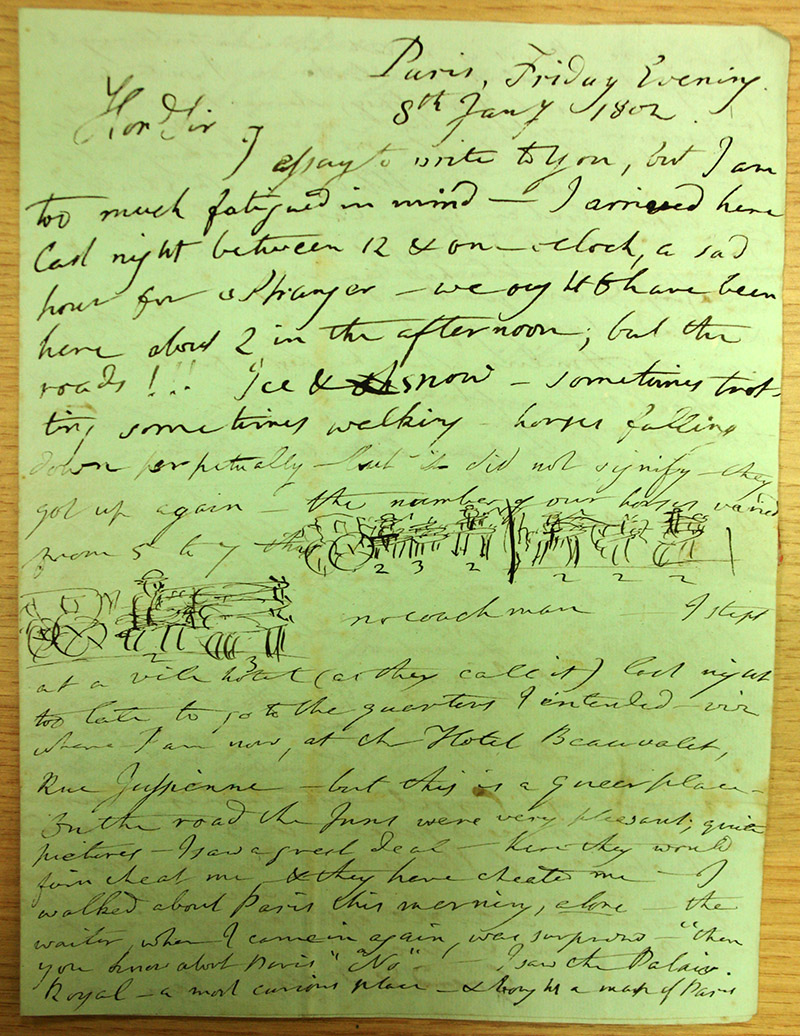

He eventually got his passport and then was held at Dover by bad weather. He visited Dover Castle and climbed Shakespeare’s Cliff. He sailed on 4th or 5th January 1802 to Boulogne and then took the Diligence to Paris – this journey was made difficult by snow and slippery roads – a fact he illustrates in another letter.

And so Thomas Manning arrived in Paris. We have several letters from this time and from his tour into Switzerland. He began to establish himself and had a tactic which he hoped would make him acceptable: “For my part, I am become quite a talker in societies – this from policy in order to make myself a welcome guest in literary parties – for if I encounter an artist or a Mathematician or a Physionomic or a Metaphysician or etc., I can’t do my host a greater service that by engaging such a man in a conversation upon his own metier, & drawing him out – & I assure you that spite of my ignorance I find plenty of subjects where I am quite at home”. Manning finds himself inpressed with Napoleon and also writes to his father of a thwarted assassination attempt – the news of which has been suppressed in France. He writes candidly about the people he has met – some of whose company he enjoys and some of whom he is intent on avoiding.

Within the letters I have so far listed, there are some indications of Manning’s interest in China. In a letter dated 8th June 1802, he writes that a Mr Taylor has introduced him to”Dr Hagar, the Conservator of the Oriental manuscripts at the National Library who is about to publish a Chinese dictionary under the auspices of the French Government. The Dr and I shall probably become intimate, as I am learning the Chinese tongue, & so curious a language is a greater bond of union among men than even Free-masonry”. By the 13th July he is writing of visiting the interior of China – something which he deems difficult but not dangerous and will not be long term. He reassures his father that he will visit England before going to China and hopes to be able to recount his adventures in his father’s parlour at Diss, on his return.

Manning also writes that he has been occupied in finishing a mathematical work which he intends to send to Carnot (Lazare Nicolas Marguerite, Comte Carnot (13 May 1753 – 2 August 1823) in manuscript. He is also involved in other analytical investigations.

So, already in a few letters we are beginning to get some idea of Manning’s character and desires. I have only been able to quote a few examples and I have only looked at letters dating to 1802, so there is much, much more to be discovered. I look forward to being able to write further blogs as the listing and cataloguing progresses.