President Tony Stockwell writes again…

Following lock-down we have cancelled events and closed the library. Compared with the plight of many organisations, however, the Society has been fortunate. The Director, collections staff, and editorial team are working from home and with great results. In meeting the challenges of Covid-19, we have been much heartened by receiving a message of support and encouragement from the Society’s Patron, HRH the Prince of Wales.

VE Day 8 May 1945

As the 175th anniversary of Victory in Europe approaches there has been much talk of rekindling the ‘spirit of the blitz’. Yet did it ever exist? Professor Steven Fielding (University of Nottingham) dismisses it entirely: ‘The spirit of the Blitz isn’t back, it’s bunk.’ (Financial Times Weekend, 21/22 March) As Mass Observation reported to the authorities at the time and as one of its founders, the polymath Tom Harrisson, revealed to the wider public in the 1970s, the ‘spirit of the blitz’ was a will-o’-the-wisp.

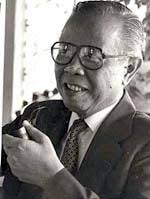

How was the spirit of the Royal Asiatic Society in 1940-45? ‘For obvious reasons’, wrote Professor Beckingham in his history of the Society, ‘the Second World War brought catastrophe.’ While he did not elaborate the nature or extent of the ‘catastrophe’, Beckingham credited Sir Richard Winstedt with the Society’s survival. From 1940 until his death in 1966 Winstedt worked for the Society ‘with total devotion’. For 24 of those years he served alternately, but without a break, as either Director or President. He would travel in from his home in Putney almost daily and ‘undertook any work that needed to be done from editing the Journal to stamping letters’. Once the war ended, he was the driving force behind the move from Grosvenor Street (the Society’s home since 1920) to 56 Queen Anne Street.

Winstedt was the last in a line of proconsular presidents, though he had not reached the heights of imperial governance achieved by some of his predecessors. Compared with Lords Hailey, Willingdon and Samuel, he was more a scholar-administrator than a proconsul. Winstedt joined the Malay States Civil Service (precursor of the Malayan Civil Service) in 1902 and was posted to a remote village in the Malay state of Perak. In 1913 he was promoted District Officer and three years later transferred to the education department. Thereafter, he remained in the field of education: he was the first president of Raffles College (the platform for the post-war University of Malaya) and he was instrumental in the creation of Sultan Idris Training College for teachers. His numerous publications on Malay language, history and culture underpinned his educational plans. His final years in Malayan service were spent as General Adviser to the Sultan of Johore, the wealthiest and most independent-minded of the Malay Rulers.

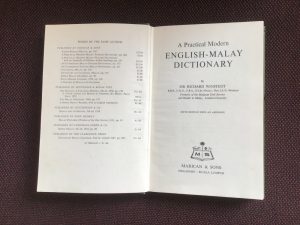

On retirement from the Malayan Civil Service in 1935, Winstedt was appointed Lecturer and subsequently Reader in Malay at SOAS (School of Oriental and African Studies, London). He was elected Fellow of the British Academy in 1945 and in 1947 was awarded the Royal Asiatic Society’s Triennial Gold Medal. Following retirement from SOAS his publications on Malay language, culture and history continued to flow and to be used. To take one of many examples: A Practical Modern English-Malay Dictionary, first published in 1952, had passed through five editions by the time I took my first steps as a post-graduate at SOAS in the late 1960s. ‘God gave us our language’, Malays have quipped, ‘Winstedt gave us our grammar.’

Following the fall of Singapore in February 1942, Winstedt acted as something of a guardian for Malay students trapped in Britain. He kept an eye on the UK Malay Students Union lest it became radicalised by, for example, Indonesian refugees from occupied Holland or left-wing British politicians such as Tom Driberg. Two such students with brilliant careers ahead of them were Ismail bin Mohd and Mohamed Suffian bin Hashim. Neither came from the princely class. Progressing from Malay schools to English language secondary schools, both won Queen’s Scholarships to read law at Cambridge. Both broadcast for the BBC to occupied SE Asia, as also did Winstedt (twice a week). Both entered the Malayan Civil Service . After independence, Ismail rose to be Governor of Malaysia’s National Bank and Suffian became Chief Justice and ultimately Lord President of the Malaysian Judiciary. In retirement Suffian would bravely stand his ground in face of Prime Minister Mahathir’s attacks on the independent judiciary. From 1978 to 1992, Tun Mohamed Suffian was President of the Malaysian Branch of the RAS.

In addition to securing the future of the RAS, Winstedt became engrossed in the campaign to secure the position of Malays in post-war Malaya. Almost as soon as Britain had lost its SE Asian empire, the Colonial Office had accepted that Malaya required a new deal involving a reappraisal of the primacy of the Malays and the treaties with Malay sultans. On the eve of VE Day the Secretary of State for the Colonies informed the Cabinet it would be necessary ‘to liberate the new Malaya from old barriers and pressures’ and ‘overcome any reactionary interests’ but that the time to take such a stand had yet to come. When the time did come a year later, Winstedt led the ‘old Malayans’ in the charge and claimed victory for Sir Andrew Caldecott, Sir Cecil Clementi, Sir George Maxwell, Sir Lawrence Guillemard and Sir Frank Swettenham (still active at 95). But, in the end, it was an unforeseen Malay nationalist movement that made the British government think again.

Tony Stockwell

Sir Richard Winstedt’s Papers (1925- c.1960s) are in the SOAS Archives, GB 102 MS 312646.

You can see something of the extent to Winstedt’s work at the Royal Asiatic Society and with other scholars of Asia within the catalogues of the Royal Asiatic Society Archives.