Journal, Book Launches and Reviews

This week’s blog begins with an update from the Archivist:

I am currently creating the catalogue for the records of the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. It has been interesting to look at records that trace back through the Journal’s history and discover the different editors, publishers, printers and some of the administration that has gone into making sure the Journal is published regularly with appropriate content. Amongst the archives are some original manuscripts, six of which are handwritten, and one is an early offprint. These are:

- Bernhard Dorn’s, ‘Description of the Celestial Globe belonging to Major-General Sir John Malcolm, G.C.B., K.L.S. &c., &c., deposited in the Museum of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland’. This is an offprint of the article published in the Transactions of the Royal Asiatic Society 1830, Volume II. The offprint contains two sketches on its inner front cover.

- A partial manuscript of ‘A sketch of the constitution of the Kandyan kingdom’ by John D’Oyly, published in the Transactions of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, 1833, Vol. 3, No. 2 (1833), pp. 191-252.

- A manuscript of an ‘Abstract Translation of an Inscription on Copper Plates found in the Fort of Miruj. Dated saka 946, or A.D. 1025’ by Mr Wathen. This is annotated by H.H. Wilson.

- ‘MSS Memoir on the Length of the Illahae Guz’ by Colonel John Hodgson. This includes a letter from Hodgson to Richard Clarke concerning the manuscript, dated 21 August 1841, and also a postscript by Henry Newnham, dated 22 May 1824. The article appeared in Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society XIII (1843), pp. 42-63.

- ‘An Account of Jerusalem from the Persian text of Nasir ibn Khusru’s Safarnamah’, translated for the late Sir H. M. Elliot, by the late Major A.R. Fuller, published in the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, New Series, Vol. 6, No. 1 (1873), pp. 142-164.

- ‘The Intercourse of China with Eastern Turkestan and the Adjacent Countries in the Second Century B.C.’ by Thomas William Kingsmill, published in the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society New Series, Vol. 14, No. 2 (Apr., 1882), pp. 74-104.

- ‘Notes on the Chinese Game of Chess’ by H.F.W. Holt, published in the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society New Series, Vol. 17, No. 3 (Jul., 1885), pp. 352-365. Holt was the Acting Interpreter, Agent and Assistant at the Ningpo Consulate in 1864.

These few articles give an indication of the wide scope of the material that has formed part of the Journal’s history. It is interesting that only these few early manuscripts have survived, one of which, the ‘Memoir on the Length of the Illahae Guz’ was considered of sufficient value to be beautifully bound.

And, of course, the Journal is still accepting articles across a wide range of subjects. But please don’t send handwritten manuscripts! Instead submit your papers electronically through ScholarOne at Cambridge University’s Cambridge Core.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

It has been a season for book launches at the Society. On Friday 8 July, Dr Hannah K. Bartos launched her book, Modern Transnational Yoga: The Transmission of Posture Practice. Dr Bartos is a member of the Centre of Yoga Studies at SOAS as well as a practising yoga teacher, and her talk covered the social organisation of modern yoga practice tracing back through history to discern who were the influencers in the transmission of yoga posture practice. Bartos, in her research using archival material and field visits to India, discovered how a small group of yogis worked to popularise their styles of yoga to mainstream audiences beyond India which, in turn, led to globalised practices. These yogis included Sivananda Saraswati (1887-1963) whose early example acted as a cornerstone for the growth of posture practice and who Bartos found has been little acknowledged. This small paragraph, of course, does not do justice to the intricacies of the development nor to the key players within the story. But her book, published as part of the Royal Asiatic Society Book Series, is now available from Routledge with the paperback edition also available to pre-order.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

On Tuesday 12 July, Professor Robert Arnott launched his book, Between India and the Aegean from Prehistory to Alexander the Great. Professor Arnott’s career has been in the history of medicine and, as an archaeologist, palaeo epidemiologist and medical historian, he has conducted excavations in Italy, Greece and Turkey with a special interest in disease and medicine in the Aegean and Anatolian Bronze Age civilisations, 2000-1100 BC. More recently Professor Arnott has been conducting research on health, disease and medicine in the Indus Civilisation, 2600-1900 B.C. These two research interests come together within this latest publication. It was thought that trade between India, the Aegean and Greece first occurred in the sixth century B.C. but there is evidence that this may have been much earlier. In the Early to Late Bronze Ages, India was an important resource for valuable and indispensable commodities destined for the elites and by examining some commodities such as tin and lapis lazuli, Arnott seeks to discover how trade developed in this era. Professor Arnott’s book is available from Oxbow Books.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

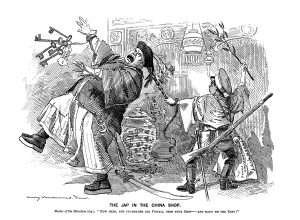

Earlier in the year the Society also held a launch for Dr Amy Matthewson’s Cartooning China: Punch, Power & Politics in the Victorian Era. If you weren’t able to attend, her lecture can be watched here and our Youtube channel holds the videos for several of our recent lectures and launches. Helen Walasek, curator of the Punch Archive and Collection until its sale to the British Library, editor of several bestselling compilations of Punch cartoons, and author of Bosnia and the Destruction of Cultural Heritage (Routledge 2015) has provided a review of Dr Matthewson’s book.

Investigating Punch cartoons of China in the Victorian Era

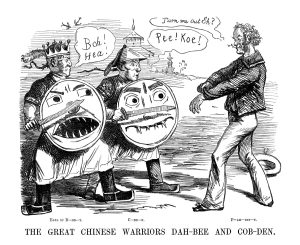

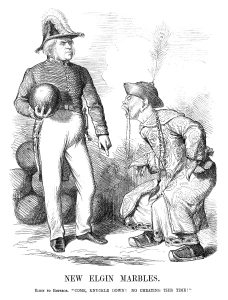

The impact of visual images – in this case, cartoons – in nineteenth-century popular print media on British public opinion and discourse are explored in a new book by Amy Matthewson, Cartooning China: Punch, Power & Politics in the Victorian Era, that was recently launched with a fascinating presentation by the author at the Royal Asiatic Society. Matthewson scrutinizes cartoons of China and the Chinese published in the satirical magazine between 1841 and the beginning of 1901, a long span of 60 years from the birth of Punch to the death of Queen Victoria. Almost midway between the magazine’s first appearance and its demise in 1992, this was not only the high point of Britain’s imperial project, but marked the end of an era that had seen a dizzying pace of change. Remarkably, over what was then a lifetime for many, Punch had only four editors – Mark Lemon (1841–1870), Shirley Brooks (1870–1874), Tom Taylor (1874–1880) and Francis Burnand (1880–1906) – and its large, full-page (and occasionally double-page) political cartoons, the ‘big cuts’, the primary focus of the book, were dominated almost entirely by three commanding figures: the notoriously xenophobic John Leech, the magisterial and hugely influential John Tenniel, knighted for his services to the arts in 1893 and whose cartoons appeared in Punch for 40 of those tumultuous years, and, as the period drew to a close, Linley Sambourne.

Punch and its cartoons have for some time been important sources for researchers of the nineteenth century, regularly cited in studies of imperialism and colonialism. Matthewson notes, however, that scholars tend to use Punch cartoons selectively and a detailed analysis of representations of China and the Chinese in the magazine has yet to appear, a gap she hopes her book will fill. The 1870s and 1880s are not surveyed, however, due, we’re told, to the virtual non-existence of full-page political cartoons on China during those decades – though they are far from being completely absent.

Betraying its genesis as a PhD thesis, perhaps too much of the book is taken up with establishing theoretical frameworks, setting out definitions of and the history of cartoons and caricatures, as well as outlining at some length the origins of Punch and the men (and their political stances) behind it, subjects exhaustively and authoritatively covered in books such as Richard Altick’s Punch: The Lively Youth of a British Institution, 1841–1851 (1998), Patrick Leary’s The Punch Brotherhood (2010) and Marion Spielmann’s hagiographic, but thorough, The History of “Punch” (1895), all of which Matthewson draws on.

Where Matthewson’s book shines, however, is her contextualisation and assessments, not only of Punch’s cartoons, but of its texts as well. She shows how attitudes towards China and the Chinese in Punch’s cartoons and text shifted from the ‘playful condescension’ of its reports of Nathanael Dunn’s Chinese exhibition in 1842 to the portrayal of China as one of the archetypal symbols of a stagnant country (the Ottoman Empire was another), in contrast to the vigour and racial and technological superiority of Britain, a trope that dominated British discourse on China for the rest of the century. Through the First Opium War (1839–1842), the Great Exhibition of 1851 and the Second Opium War (1856–1860), alongside its symbolic embodiment, the dragon, the queue and stiff elaborately embroidered robes and shoes became signifiers of China – even for those British politicians so ‘un-English’ as to sympathise with China. Now China and the Chinese were portrayed as cruel and barbaric – no longer oddly-dressed amusing foreigners, but animalistic and vicious, John Tenniel’s depictions of personified China verging at times on the excesses of his representations of the Irish. By the time of the First Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895, Punch began comparing China unfavourably to Japan, which, though often depicted as a naughty boy, seemed to be emulating the West in its drive and dynamism.

Few of Punch’s Victorian readers in Britain would have been to China, let alone encountered a living Chinese person – even in the 1890s London’s Chinese community numbered only around three hundred. But Punch’s very popularity both in Britain and abroad makes the views expressed in the magazine (both visual and written) key markers, as Matthewson notes, of ‘imperialism, knowledge production, and dissemination’ and the ‘crystallisation of particular notions and attitudes’.

The magazine’s audience abroad were European elites, expatriate British colonials and local readers. Richard Scully’s A Comic Empire: The Global Expansion of Punch as a Model Publication, 1841–1936 (2013) gives an account of just how influential Punch was (particularly its cartoons), inspiring a host of imitators and emulators far from the metropole, created not only by nostalgic expatriates, but by local actors themselves, whose periodicals, prompted by a burgeoning nationalism, characteristically challenged imperialism and colonialism. Still, their inspiration came from Punch – despite its jingoism. China’s first locally produced Punch-like publication, Shanghai Puck, did not appear until the twentieth-century, though there were short-lived expatriate imitators in the nineteenth (like The China Punch). The papers in Asian Punches: A Transcultural Affair (2013) vividly explore the diversity of these imitators in colonial or ‘semi-colonised’ settings in one part of the world, including China.

Although Matthewson (like many others) situates Punch as revealing of the preoccupations of the Victorian upper-middle and upper classes, she cites (more than once) the example of a mail carrier in Wales recognizing Lord Palmerston from his caricature in Punch. This is a subject that has been little investigated. The ubiquity and reception of Punch cartoons outside the magazine and their reproduction in other media, not to mention the presence of the magazine itself in libraries and reading rooms not always frequented by those perceived by today’s researchers as its target readership, appears to have given its large political ‘cuts’ an audience at all levels of Victorian society. Where did the Welsh mail carrier see those Punch cartoons? As Matthewson’s book amply shows, it was the immediacy of the images that had an impact, even if wading through columns of dense type did not appeal.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

We are grateful to Helen Walasek for this review. Dr Matthewson’s book is also published by Routledge with the paperback version already available.