Introducing the new JRAS Editor Professor Daud Ali / Bicentenary of the Société Asiatique

Professor Daud Ali

Last year we were pleased to announce the appointment of Professor Daud Ali to Editor of the journal following the end of Professor Ansari’s tenure. Journal submissions, which had been closed during the handover period, reopened this week. To coincide with the resumption of the Journal’s activity, Professor Ali has kindly written a piece for the blog introducing himself and his plans for the Journal.

————————————————————————————————————–

I am an historian of early and medieval India. I was trained in the History Department at the University of Chicago and during the formative years of my career served as one of four South Asian historians in the department of history at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London. Since 2009, I have been in an area studies department at the University of Pennsylvania. My research has spanned a wide variety of subjects and themes relating mostly to pre-Sultanate India. I am very honoured as well as excited to take on the editorship of the JRAS. As incoming editor, I would also like to thank Sarah Ansari for her many years of service to the journal, and I hope to not have to rely too much on her wisdom during the initial period of my tenure.

My vision as editor of the journal at this point is three-fold. First, I hope to pursue the traditional mission of the journal with its interdisciplinary strengths in various fields related to Asian Studies, as well as ensuring that the journal engages with important new trends and directions in the field of Asian Studies. This is crucial in keeping the journal relevant and at the forefront of the fields it covers. Second, I would like to raise the profile of the journal in the US academic environment, where it is surely recognized but often with a hint of reticence by non-specialists. Our goal should be to increase its name recognition among non-specialists so that it is seen as an attractive publishing destination for junior scholars thinking of their tenure dossiers. How this can best be achieved will be a matter for discussion. Finally, I intend on working towards the journal’s healthy future in an increasingly complex, financially threatened, and perhaps uncertain online publishing environment. This will mean working very closely with our colleagues at Cambridge University Press, especially Sally Hoffmann who is the executive publisher for humanities and social science journals, and continuing to develop in a flexible and pragmatic way the essential management and administrative underpinnings of the journal, based in the office in Stephenson Way. To this end one of our first tasks will be to pursue the possibility of establishing a separately designated book review editor to handle the demanding job of managing and coordinating book reviews in an environment where the circulation of printed review copies is increasingly being seen as superfluous.

My style of leadership will be consultative and transparent. I will work with the larger editorial board as well as a team of associate editors in all matters relating to the journal—and particularly to develop content, strategy and innovation. There will be more communications from me in the near future, but for the moment I want to say once again how excited I am to take on this role and look forward to the feedback of the RAS community.

————————————————————————————————

Bicentenary of the Société Asiatique

Last week Dr Alison Ohta, Director of the Royal Asiatic Society, gave a presentation to members of the Société Asiatique in celebration of its bicentenary. For this week’s blog Dr Ohta has written about the early relationship between the two learned societies which was the subject of her presentation.

This year marks the bicentenary of the foundation of the Société Asiatique in Paris. It was the first society of its kind in Europe promoting research on Asia and providing the necessary support for the study of oriental languages and acquisition of manuscripts. Its inaugural meeting held on the 1st April 1822 was presided over by the Duc Orléans, the future King Louis Philippe (1793-1830). The Royal Asiatic Society was founded in London one year later on the 15th March by Henry Thomas Colebrooke, followed by the Deutsch Morgenländische Gesellschaft in Halle in 1845.

In June 2021, I received an invitation from the Société Asiatique to give a presentation at a colloquium celebrating this important milestone on the 27th and 28th January 2022. The title of my talk was Une entente cordiale: La Société asiatique and The Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland in which I examined the close relationships that existed between both societies in their early years. I had hoped to attend in person but the constraints imposed by Covid and the associated uncertainties interfered so I gave my presentation by Teams to the colloquium which was held in the magnificent Salle de Séances in the Palais de l’Institut de France.

Henry Thomas Colebrooke was among the first foreign scholars elected as a corresponding member to the Société Asiatique in 1822 and likewise on the foundation of the Royal Asiatic Society several members of the Société Asiatique became fellows and donated their publications to our library. These included Baron Silvestre de Sacy (1758-1838), the distinguished orientalist and diplomat who was Professor of Persian at the Collège de France and the first President of the Société Asiatique and was described by Edward Said as the teacher of nearly every major orientalist in Europe; Chevalier Jaubert, a distinguished diplomat and scholar who became President of the Société Asiatique in 1834; Abel Rémusat the renowned sinologist who was the first secretary of the Société in 1822 and finally Julius Mohl, a student of de Sacy who was responsible for the translation of Firdawsi’s Shahnama in 1826 and later became Secretary and President of the Société Asiatique.

Members of both societies attended meetings when visiting either capital although not always very happily. Eugène Burnouf, (1801-1852) the great Sanskrit and Buddhist scholar who served as secretary of the Société wrote to his wife of his experience attending a meeting of the RAS in London:

‘Nothing is more boring or vacuous… These great London scholars do nothing and unless the government comes to the rescue, it is doubtful that they will have enough means to publish the Journal two years hence’.

A series of letters in the autograph book that once belonged to Brian Houghton Hodgson (1890-94), now in our collection, illustrates the relationship that existed between the two societies. Hodgson, as many of you know, was British resident in Kathmandu from 1824-1843 and devoted the 23 years he lived there to the study of the peoples, culture, customs, religion, natural history and architecture of Nepal. He contributed more than 170 articles to the journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal and the Royal Asiatic Society. He employed Nepali artists to make drawings of the buildings of the Kathmandu Valley which constitute the earliest representations of Buddhist architecture of Nepal.

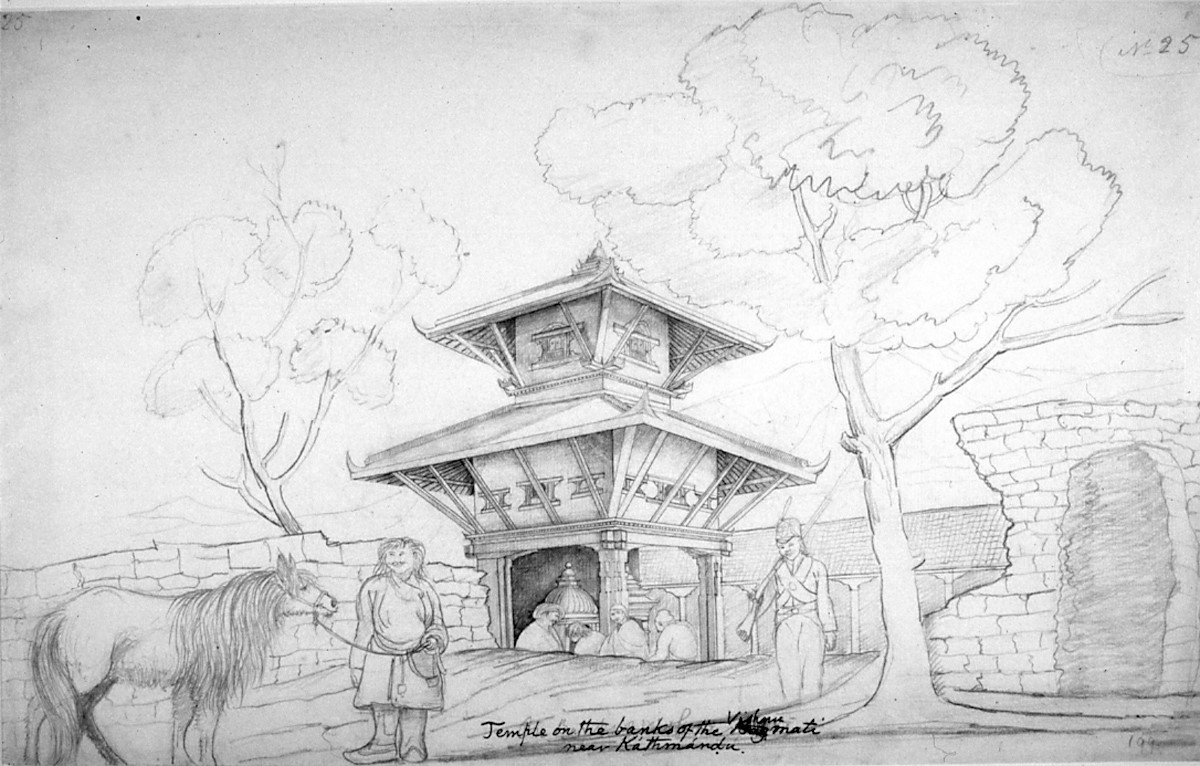

The Temple on the River Vishnumati, signed Raj Man Sigh, 1844, RAS. 022.025, 45.5 x 32.2cm

He also commissioned paintings of the local birds and mammals by Nepali artists which today reside in the Natural History Museum and the Zoological Society. The autograph book contains one letter from the Muséum d’Histoire naturelle in Paris dated 1835, thanking Hodgson for specimens of Nepali birds which he had sent to them with Dr. Nathaniel Wallich (1786-1854) the distinguished naturalist.

Hodgson’s great interest was Buddhism and he began collection and copying manuscripts in Nepal for study. His first essay on the subject was published in the Transactions of the Royal Asiatic Society in 1824. The RAS collection contains several Buddhist manuscripts donated by Hodgson, the most notable being the Aṣṭasahasrikā prajñāpāramitā which is written on palm leaf and contains several illustrated folios.

Hodgson MS 1, a copy of the Aṣṭasahasrikā prajñāpāramitā (The Perfection of Wisdom in 8,000 lines), thought to date from the 12thcentury CE.

A letter from Eugène Burnouf to Hodgson dated the 7th July 1834 requested Buddhist manuscripts be sent from Nepal to the Société Asiatique. A later letter from M. Eugène Jacquet, an active member of the Société, informed Hodgson that he had been elected an honorary member. In 1835 Hodgson sent 24 Buddhist manuscripts to the Société and a letter dated 15th July 1837 from Burnouf thanked Hodgson for 3 boxes of copies of manuscripts ( thought to number 64). Burnouf informed Hodgson that the Société would now award him a gold medal for his work (awarded in 1838) and offered the sincere thanks of the Council of the Société Asiatique. He also wrote that the sum of £60 would be sent to him – the equivalent of about £6,000 today. Hodgson had also sent Burnouf a further 59 manuscripts. It was these that provided the basis for Burnouf’s work entitled Introduction à l’histoire du Buddhisme Indien which was published in 1844 and is considered the most influential work on the subject in the 19th century. In 1852 Burnouf published Le lotus de la bonne loi which included a dedication to Hodgson:

A Monsieur Brian Hodgson, membre du service civil de la Compagnie des Indes, comme au fondateur de la veritable étude du Buddhisme par les textes et les monuments.

In 1838, Hodgson received a letter from the Minister of Foreign Affairs, M.Guizot, offering him the Légion d’honneur which was sent to him in Nepal. Hodgson must have been delighted with this recognition of his work. However, this joy was short lived because in 1840 he received another letter from the French Legation in Washington informing him that the medal was not destined for him but another Hodgson (see note below) who had been American consul in Algiers and was now living in Washington.

Excerpt from the letter:

26 Novembre 1840

Monsieur, Il résulte d’une pièce datée de Népal le 17 avril 1839, signée par vous et transmise au Gouvernement Français que vous reconnaissez avoir reçu la décoration de l’ordre Royal de la Légion d’honneur de France.

C’est par une erreur qui reste jusqu’à présent inexplicable que cette décoration vous a été adressé car elle était destinée à M.Hodgson, ancient consul des États Unis à Alger et aujourd’hui interprète du gouvernement à Washington qui est en possession du diplôme de L’ordre de la Légion d’honneur dont vous avez la décoration.

Je regrette vivement Monsieur de devoir réclamer de vous cette décoration mais j’ai eu en reçu l’ordre de mon gouvernement et je vous serai particulièrement obligé de me la faire parvenir par une voie sûre à Washington pour qu’elle soit réunise à son légitime propriétaire.

L’Envoyé extraordinaire et Ministre Plenipotentionaire de S.M. le Roi des Français

Ad.de Bacourt

Unfortunately, we are only privy to the letters addressed to Hodgson so we have no idea how this news was received. However, Hodgson must have written to Burnouf whose letters are filled with consternation with this affaire incroyable. Burnouf explains how a visit was paid to M.Guizot, the Foreign Minister to have the Légion d’honneur reinstated and in 1841 Julius Mohl wrote to Hodgson in English from the Société Asiatique with a heartfelt apology:

Letter from Julius Mohl dated October 27, 1841

I have the honour and the very great pleasure of announcing that M.Guizot, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, has just sent me a letter for you enclosing the order of the Legion of Honour and begging you to excuse the unfortunate mistake, confirming you fully in your right and expressing thanks from the French government of the great service you have rendered to science and to the Asiatic Society.

A letter from Burnouf three months before he died in 1852 expresses his eternal gratitude to Hodgson who by then had retired to Darjeeling. This was included by his daughter Laura de Lisle in a selection of her father’s letters which she later published. The final letter in the series is from Laura who visited the Hodgsons in London to copy a selection of her father’s letters in which she refers to Hodgson as a noble and generous friend to her father.

Portrait of Brian Houghton Hodgson, c.1890

By Charles Alexander, British Library.

Such relationships and exchanges stand as witness to the close collaboration and active exchanges that existed between scholars in France, Britain and Germany, as they pioneered research in the various fields associated with the development of Asian Studies. We wish the Société Asiatique another 200 years of success and hope that the entente cordiale that has existed since its foundation endures. The Société Asiatique will continue its celebrations in the autumn with an exhibition of its treasures at the Collège de France.

Note:

This was, in fact, William Brown Hodgson (1801-1871) who had been sent to Algiers as a pupil diplomat in 1826-9 to learn Turkish and Arabic. He was a distinguished scholar, diplomat and a Foreign Member of the Royal Asiatic Society who published a translation of a Berber manuscript in the Society’s journal Vol. 4, No. 1 (1837), pp. 115-129. He was one of the first Americans to receive the Légion d’honneur.

—————————————————————————————–

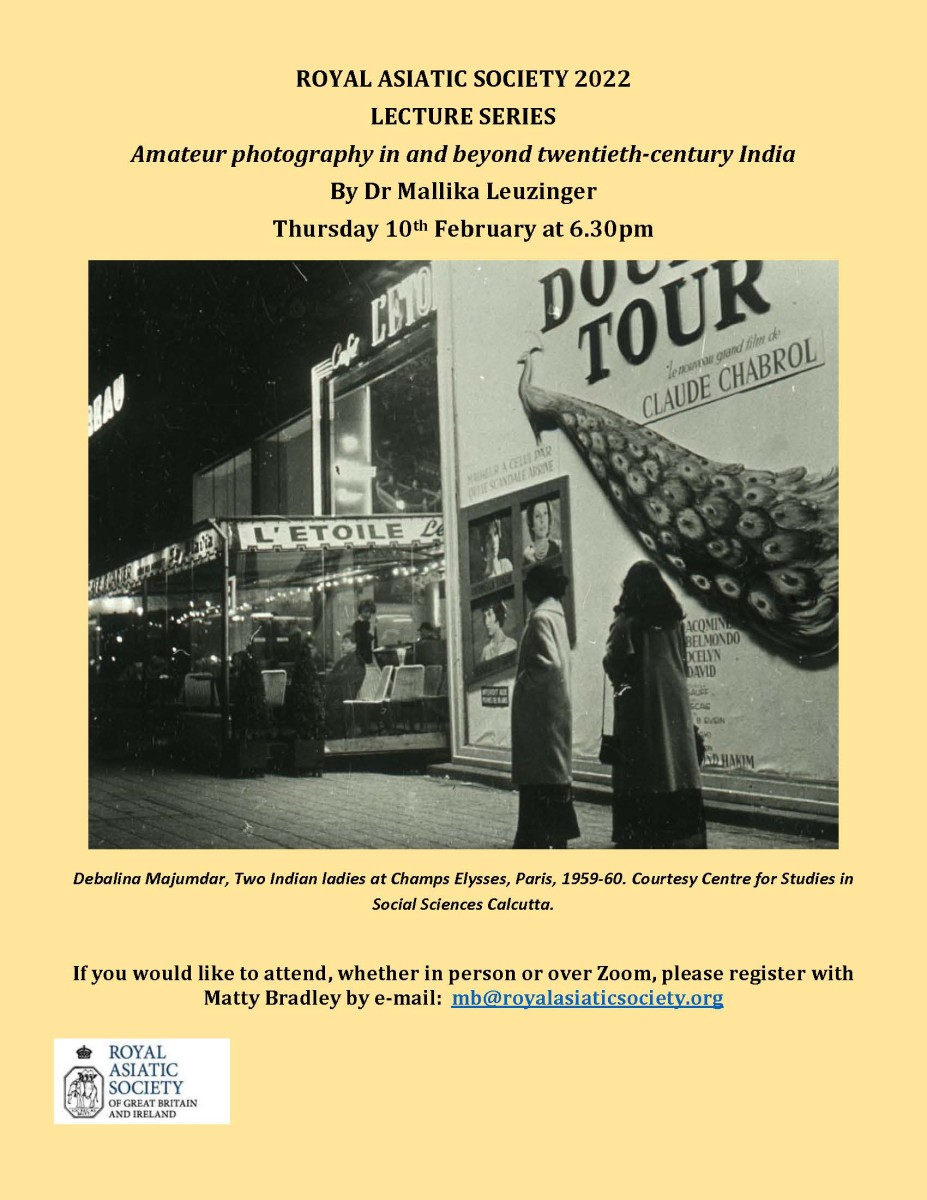

Dr Mallika Leuzinger: Amateur photography in and beyond twentieth-century India

Please join us at 6.30pm on Thursday February 10th for a hybrid lecture by Dr Mallika Leuzinger entitled Amateur photography in and beyond twentieth-century India.

When you register, please specify whether you plan to attend at the Society ‘in person’ or ‘online only’.

You can register by emailing Matty Bradley at mb@royalasiaticsociety.org

This talk, based on Dr Leuzinger’s doctoral research on camera politics in South Asia, reflects on the photographic engagements of middle-class women – and citizens of a newly independent and non-aligned nation – in the twentieth century. Debalina Majumdar (1919-2012) and Manobina Roy (1919-2001) were twins who grew up in the town of Ramnagar and were gifted an Agfa Brownie by their father Binod Bihari Sen Roy, a tutor employed by the Maharaja of Benares and a Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society of Great Britain. Alongside images of their everyday life, relatives, and acquaintances who included Tagore and Nehru, they produced striking street photography and portraiture during travels to the USSR and London in 1959-60. These circulated through regional and transnational photographic associations and The Illustrated Weekly of India, and now figure in their children’s memories and homes, and in institutional and journalistic endeavours to foreground Indian women in history. Revisiting this ebb and flow through the lens of ‘amateurism’ excavates the confrontations and convergences of gender, race, class, family and nation entailed by their photography, as well as its cosmopolitan possibilities.

Mallika Leuzinger is a researcher in Colonial and Global History at the German Historical Institute London. She holds an MPhil in Gender Studies from the University of Cambridge and PhD in History of Art from University College London and was a Fung Fellow at Princeton University. She is working on the book Dwelling in Photography: Intimacy, Amateurism and the Camera in South Asia, and a new project on digital archives and the politics of crowdsourcing history.