Guest post: Olly Akkerman – A Neo-Fatimid Treasury of Books

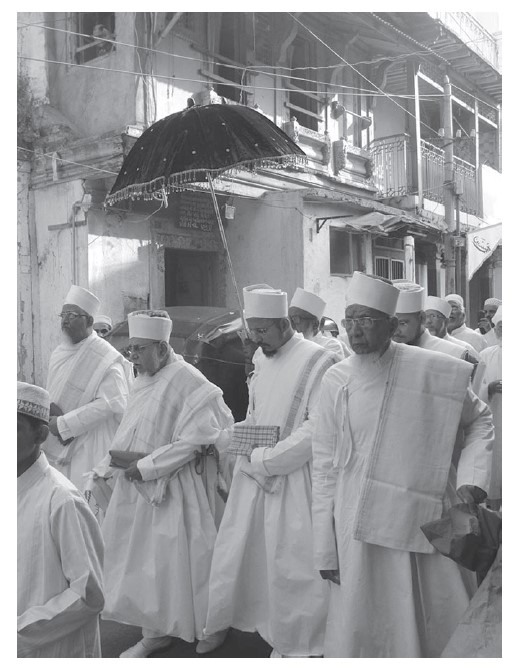

Given the highly digitalized world we find ourselves in, it may be hard to imagine that handwritten manuscripts continue to play a central role among communities today, not only as books that are read, but also as tangible carriers of blessings, secret objects, as well as symbols of heritage, authority, and identity. In my monograph, A Neo-Fatimid Treasury of Books, I am interested in the question of how people construct a sense of togetherness through their manuscripts. It tells the story of the Alawi Bohras, a small Muslim community from Gujarat, India, and the survival of one of the last living Arabic manuscript cultures of the Muslim world.

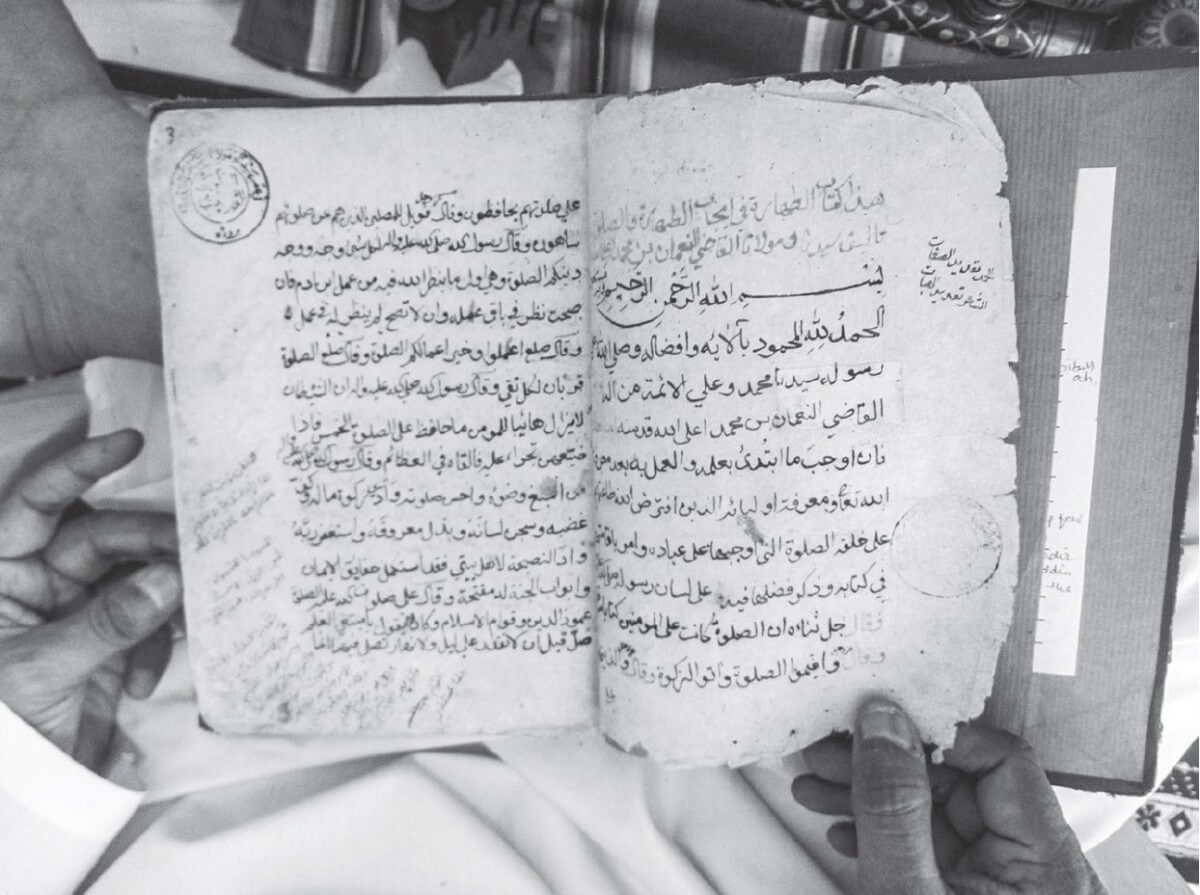

The Alawi Bohras trace their living manuscript culture, as well as themselves, over the Western Indian Ocean back to the mountains of Northern Yemen and the royal books treasuries of the Fatimids in Egypt. The Isma’ili-Fatimids ruled much of North Africa and the Mediterranean from the tenth to the twelfth century and were known for having one of the largest libraries of its time. After the fall of the empire in the late twelfth century, its books were destroyed due to ideological reasons, a paradigm which has dominated the field for the last decades.

Based on extensive archival and ethnographic fieldwork among the Alawi Bohra community in Baroda, I argue that, despite different temporal and spatial parameters, the manual transmission of Fatimid manuscripts is as much alive today in Gujarat as it was centuries ago. Not only did I learn that Fatimid and post-Fatimid titles are still read and copied today in Gujarat, it is through scribal traditions and ritualised practices of transmission that the Alawi clerics connect their modern manuscriptorium in Gujarat with the historic Isma’ili book treasuries of medieval Yemen and Fatimid Cairo, and see themselves as the heirs of the Fatimids.

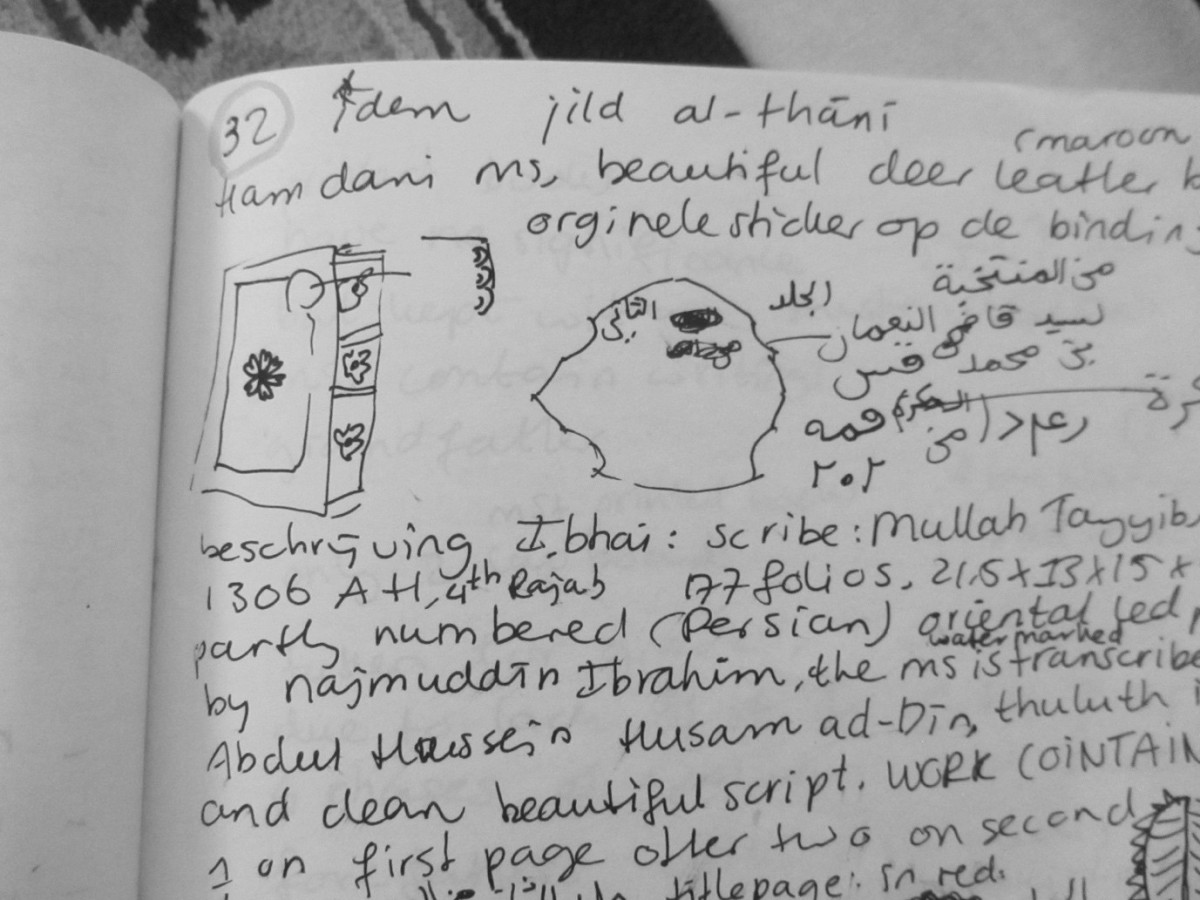

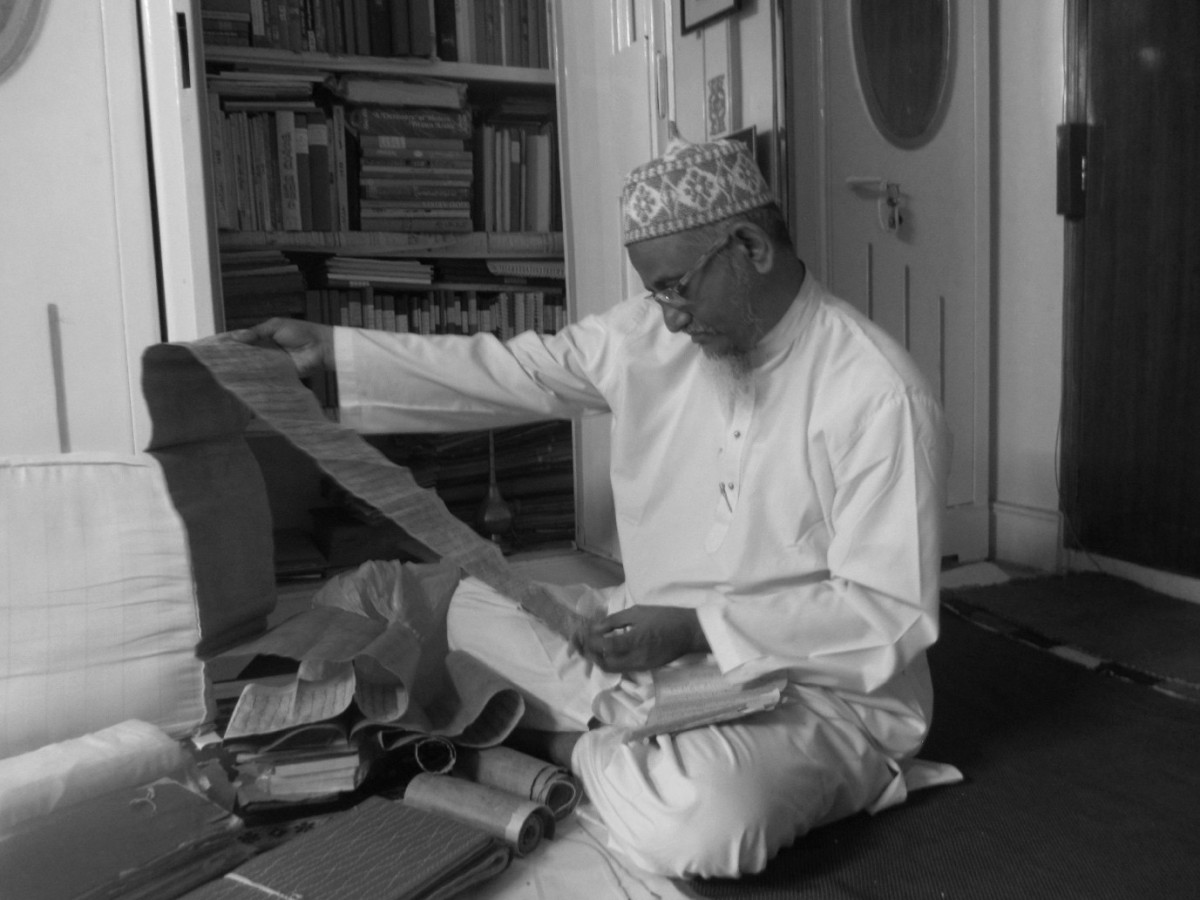

I had the great fortune to gain access to the world Alawi Bohras, a community that is usually closed to outsiders, and, after months of gaining trust and initiation, access the khizanat al-kutub or treasury of books. From total outsider I was appointed “court historian” of the community by the Alawi Bohra royal family, and became in charge of cataloguing the manuscripts of the khizana. What thus started as ‘going to the archives’ led to my role as ‘accidental ethnographer’ of the community and its manuscripts. I explore this process, during which I learnt to negotiate my presence as a ‘lady’ scholar’ in a dominantly all-male environment- working with secret texts, in detail in the book. In this new role, I learnt to observe the daily life of the treasury of books, and understand the social meaning of its sacred books through the lens of the community, rather than my own sterile notions of what a manuscript is. By reading and cataloguing the manuscripts together with their custodians, an entire new world unfolded.

One could argue that A Neo-Fatimid Treasury of Books is essentially an ethnography of manuscripts and the people who preserve, copy, collect, enshrine, and venerate them. In focusing on the particular localised social life of the khizana, it moves beyond the frequently articulated idea that manuscripts are inert objects of material culture, imprisoned in the histories of their creation. I argue, instead, that manuscripts have a rich social life through their interaction with people and communities over time and space.

As such, the book thus shifts the focus on manuscripts entirely from their study as material objects to the social framework in which they gain meaning through their interaction with readers, communities and their day-to-day lives. I have called this approach Social Codicology, a new disciplinary practice which humanises the people who write, use and venerate manuscripts in a living understanding of Islam as a local human experience. The actor- and agency-oriented approach of Social Codicology documents the many facets of a South Asian diasporic community’s locally lived Shi’i, Isma’ili and distinctly Arabic Indian Ocean experience of Islam. Through questions of gender, agency, veneration and identity formation, A Neo-Fatimid Treasury of Books thus engages with the larger question of how Islam functions as a localised practice through texts, manuscript culture, secrecy and community in Gujarat, but also across the western Indian Ocean before the emergence of external factors, such as colonialism, the introduction of print, and more recent universalising understandings of Islam.

As a study in Social Codicology, this monograph is an invitation to reflect critically about the larger field of Islamic manuscripts, our positionality, gender, ethics, provenance, as well as the preservation of cultural memory of the Muslim world. It highlights the importance of doing the “hands on” work of codicology which often gets lost on the screen. As such, it is an argument for bringing the materiality of the book, and the social practices that give meaning to it, to the centre of our enquiry. Such a perspective will not only bring new perspectives to the field, but also has the potential to assist communities in safeguarding and preserving their written heritage.

As I argue in the book, even though the digital preservation of living and historic manuscript and documentary cultures is admirable and important, for the next generations, their emic meaning, and thus a sense of community, will be lost on the screen. As was recently argued in the New York Times[1], climate change dramatically affects manuscript cultures and their preservation, especially among communities in the the Global South. If we do not make the effort of understanding why these traditions matter to the people they belong to and take their physical materiality seriously, we will be unable to protect and preserve the cultural memory of those communities that are less known to the world: we run the risk of losing them for good.

Note: all pictures are taken by the author unless stated otherwise and can be found in A Neo-Fatimid Treasury of Books.

[1] Emmett Lindner, Racing to Protect Books From Climate Change. New York Times Jan. 9, 2023, Section C, 3.

Many thanks to Dr Akkerman for this week’s blog post. The book launch for A Neo-Fatimid Treasury of Books took place at the Society at the end of last year. The event can be viewed on the Society’s Youtube channel:

We would also like to congratulate RAS Fellow Professor William Gould on the publication of Ambekdar in London which he co-edited with Santosh Dass and Christophe Jaffrelot. For more information please see the publisher’s website.

3 Comments

Join the discussion and tell us your opinion.

[…] are usually defined by Western understandings of nation-states and modern territorial borders, Olly Akkerman, one of the few researchers on Arabic manuscripts and Shi’i Islam, underscores the role […]

[…] are usually defined by Western understandings of nation-states and modern territorial borders, Olly Akkerman, one of the few researchers on Arabic manuscripts and Shi’i Islam, underscores the role […]

[…] are usually defined by Western understandings of nation-states and modern territorial borders, Olly Akkerman, one of the few researchers on Arabic manuscripts and Shi’i Islam, underscores the role […]