The Papers of Johannes Rahder

Johannes Rahder (27 December 1898 — 3 March 1988) was born in Lubuk Begalung, now a district of Padang, Indonesia, where his father was governor of western Sumatra. He studied first in Leiden (1917-24), then in Brussels (La Vallée Poussin) and Paris (Pelliot) from 1924-28. He gained his PhD at the University of Utrecht in 1926 under the supervision of Willem Caland (1859 – 1932), the Dutch Indologist, philologist, numismatist and translator. Rahder studied the Daśabhūmikasūtra, the ‘Scripture of the Ten Stages’, the definitive scriptural account of the ten stages (daśabhūmi) of Buddhism. He completed a translation which was subsequently published.

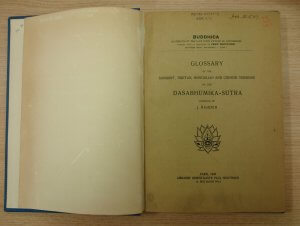

Rahder also published, in 1929, this Glossary of the Sanskrit, Tibetan, Mongolian and Chinese Versions of the Daśabhūmikasūtra revealing something of the breadth of his research. This copy was sent to the Royal Asiatic Society by the Librarie Orientaliste, Paul Geuthner, in April 1929.

In 1929 he was in Japan as the chargé de mission scientifique at Maison Franco-Japonaise in Tokyo, working on the Hōbōgirin, le dictionnaire encyclopédique du bouddhisme d’après les sources chinoises et japonaises, francophone scholars being keen to study texts on Buddhism from a wide range of sources. Rahder returned to Utrecht in 1929 to become Professor of Sanskrit and Comparative Linguistics and in 1931 moved to Leiden to become Professor of Japanese. This post gave him the opportunity to travel in Japan and Korea. In 1937-38 he became Visiting Professor at University of Hawai’i, which eventually led to his decision to leave Leiden, in 1946, to became a full Professor in Hawai’i. However that was short-lived. In 1947 Rahder moved to Yale University where he stayed until his retirement in 1965.

Rahder had a keen interest in Buddhism and linguistics. He not only studied Sanskrit and Pali, but also Chinese, Japanese and other languages so he was better able to access original source material. He made significant contributions to the wider understanding and influence of Buddhism as well as the etymology of several languages.

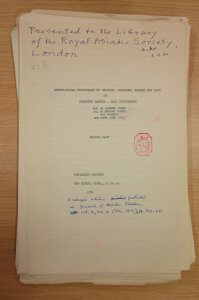

So why my interest in Johannes Rahder this week? I have been sorting through some boxes of uncatalogued material. They are mostly institutional records connected to the administration of the Collections of the Society. But amongst these I’ve found a few items that don’t fit that category. In 1960, Johannes Rahder sent to the Society typed copies of the second, third and fourth parts of his Etymological Vocabulary of Chinese, Japanese, Korean and Ainu. These I discovered among the other papers.

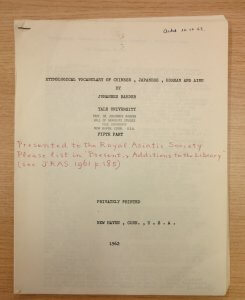

The original gift was followed, in 1962, by the fifth part which also bears the handwritten note, ‘Presented to the Royal Asiatic Society. Please list in “Present. & Additions to the Library” (see JRAS 1961 p.185)’.

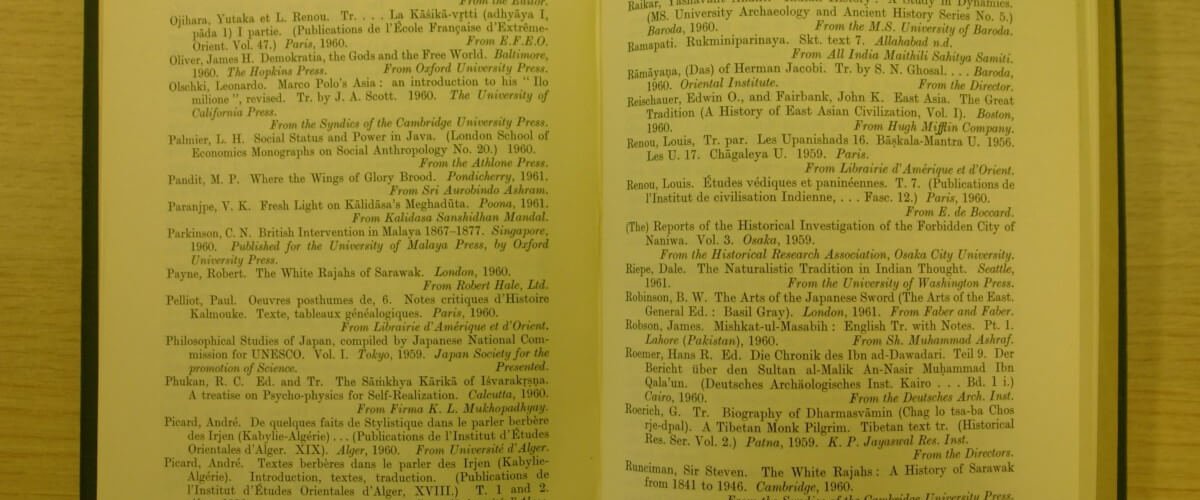

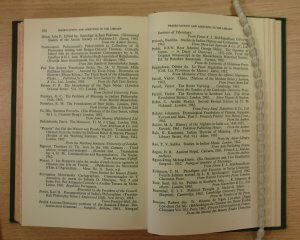

This intriguing inscription took me to the Society’s Journal. Looking on page 185 in the 1961 Journal (pictured above) I found that Rahder’s publication had been listed in the ‘Presentations and Additions to the Library’ section, though as Parts 1, 2 and 4. Wondering whether we also had the first part led me to a hunt in the strongroom in all the possible locations where an uncatalogued item might be. There are not many such locations any more and my search proved fruitless. I therefore suspect that the parts were inaccurately recorded in the Journal. I also wondered whether Rahder’s request for his fifth part to be acknowledged in a similar manner had been honoured. I looked in the 1962 Journal – nothing! However, on turning to the Presentations and Additions section in the 1963 Journal, his gift was acknowledged as he had asked.

Though Rahder considered the Vocabulary as privately printed, because it is not bound, it is not really suitable to be put with our Library collections. After discussion with the Librarian, Edward Weech, we decided the best way to catalogue these papers would be as a small collections of personal papers. Doing the research for this blog post has also provided me with the information that I need to be able to create the catalogue. So guess what my next task will be once I’ve posted the blog?