The Charles H. Norchi Prize

The Royal Asiatic Society is delighted to announce the launch of the annual Charles H. Norchi Prize for the publication of a book on Afghanistan in English during the two previous calendar years.

Nominations are invited for books on Afghanistan published during calendar years 2023 and 2024. Submissions must include a paragraph of not more than 500 words detailing why the book should be considered for the Prize, accompanied by a short biography of the author and one letter of support. The value of the annual Prize is £500. Nominations for the Prize will close on January 31st 2025. The nominations will be considered by a panel of judges and the winner will be announced by the end of April 2025. The Prize will be awarded on the recommendation of the judges. No one shall receive the Prize twice for the same publication. The winner of the Prize would normally be expected to present a public lecture at an open meeting of the Society, either in person or remotely, subject to arrangements mutually agreed between the winner and the Society.

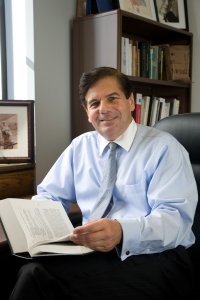

This Prize has been offered by Dr. James J. Busuttil to honour the work and distinguished career of his friend and colleague Professor Charles H. Norchi, Benjamin Thompson Professor of Law at the University of Maine, who has spent four decades researching, writing and advising on Afghanistan.

Born in Dublin, Ireland, Dr. Charles H. Norchi was among those “Afghan hands” who cut their teeth in the Soviet War of the 1980s, first as a journalist, then as a human rights lawyer. He reported on many aspects of Afghan life during armed conflict—refugees, development, humanitarian deprivations, Mujahadeen and the foreign policies of States then shaping the trajectory of Afghanistan. As a human rights advocate, Dr. Norchi served as Director of the Independent Counsel on International Human Rights, working with the Committee for a Free Afghanistan and later as Executive Director of the International League for Human Rights. As a university professor, Afghanistan remained at the centre of his teaching at Yale, Sarah Lawrence, Smith, Harvard and Maine, where he holds the appointment of Benjamin Thompson Professor of Law in the University of Maine School of Law. His subject areas are International Law, Law of the Sea, Human Rights, International Security, the Arctic and Afghanistan.

In addition to being a Fellow of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, Professor Norchi is co-Chair of the International Institute for Law, Science and Policy (Geneva, Switzerland), Visiting Professor in the Climate Change Institute of the University of Maine and the Institute for the Environment at Brown University, a Fellow of the World Academy of Arts and Sciences, and a Fellow of the Explorers Club. He has served as Visiting Professor at City University of Hong Kong School of Law, Peking University School of Law, Human Rights Fellow at Harvard Law School, Research Fellow in the Center for Public Leadership in the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University and Myres S. McDougal Fellow in Yale Law School. He holds an A.B. from Harvard College, a J.D. from Case Western Reserve University School of Law and an LL.M. and a J.S.D. from Yale Law School.

In addition to teaching and writing, Professor Norchi regularly advises international and civil society organisations, governments and law firms while remaining engaged with Afghanistan and her people.

All correspondence to be addressed to Dr. Alison Ohta: ao@royalasiaticsociety.org

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

We are grateful for the endowment of this prize and in conjunction with this, Professor Norchi has kindly provided this blogpost about his life and career in Afghanistan:

The Durand Line and I, Reflections upon the occasion of the RAS Afghanistan Prize

The Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland was founded in London in 1823 for, as stipulated in its Royal Charter from King George IV, ‘the investigation of subjects connected with and for the encouragement of science, literature and the arts in relation to Asia’. Since its founding, members of the Society have travelled to Afghanistan producing important chronicles and scholarly works. I am honoured and humbled to follow in their footsteps by having my name associated with this Prize and wish to thank Dr James J. Busuttil, who catalysed this initiative. In addition to recognising and promoting serious work on Afghanistan, the hope is that this Prize will shed yet another light on the plight of the Afghan people.

My first real encounter with Afghanistan was during the Soviet war of the 1980s, working as a journalist based in Peshawar, Pakistan near the Kyber Pass. Peshawar was the seat of the Afghan Government-in-Exile and the political parties of the Mujahadin organizations then fighting the Soviets. Being across the border from Afghanistan adjacent to Tribal Agency meant the government of Pakistan and others could maintain contact with key players and sometimes exercise influence. As I have written elsewhere, “journalists, mercenaries, volunteers and spies came to Peshawar for the war next door. This was the quintessential peripheral war town.”[1]

Most of us, the newcomers and the seasoned, stayed at Dean’s Hotel. Among the noteworthy perennial residents were Louis Dupree, who as a young Princeton professor had published Afghanistan, and his wife, Nancy, who was also an accomplished anthropologist. They patiently tutored the newly arrived and counselled the seasoned. Other scholar-travellers of the period included Whitney Azoy, whose special expertise was the Afghan game Buzkashi, the French sociologist Olivier Roy, anthropologist Tom Barfield and political scientist Barney Rubin, among others. But we especially learned from Afghans—such as Rasul Amin, who formed the Writers Union of Free Afghanistan, and Professor Seyyed Majrooh, who founded the Afghanistan Information Centre (AIC), a centre for liberal Afghan intellectuals for which he was assassinated by fundamentalists.

The war was on the other side of the border. The code language for slipping across the Kyber Pass and disappearing was “going inside”. Some of my newspaper reporting headlines from that time were “Afghans must fight their own hills”, “Afghanistan lies bloodied and battered from Soviet Terror”, “End Game for Afghanistan?” and “US Walks Away from Afghanistan Vacuum”. From Peshawar, going inside meant entering the tribal belt and crossing the Durand Line.

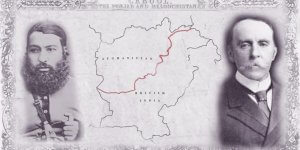

The 1893 Durand Line Agreement separating Afghanistan and India, later Pakistan, was affirmed by Afghan-British Treaties of 1919 and 1921. But much of India’s north-west frontier, including the city of Peshawar and the tribal agencies, remained traditional Pushtun territory. Tribes on each side of the Durand Line shared a common ethnic identity and looked to Peshawar as their capital. At the time of Indo-Pakistani partition, Kabul demanded the Pushtun areas be given independence rather than a choice between India and Pakistan. Among the excellent histories of the Durand Line is Afghanistan: A History from 1260 to the Present by Royal Asiatic Society Fellow Jonathan L. Lee.

As my career moved from journalism to international law, I continued traversing the Durand Line but viewed it through a different lens; appraising the line and its context as a jurist. I was mindful that the Afghan government had initially objected to Pakistan’s membership in the United Nations. In 1949, the Afghan government convened a loya jirga in Kabul following the Pakistan bombing of an Afghan border village. The jirga declared support for an independent Pushtunistan insisting that Pakistan was a new state rather than a successor state to British India and its obligations and borders under international law. Thus, previous treaties concluded with the British that pertained to the border were declared null and void. This included, inter alia, the Durand Agreement, the 1879 Treaty of Gandamak, the Anglo-Afghan Pact of 1905, the Treaty of Rawalpindi of 1919 and the Anglo-Afghan Treaty of 1921. When a state ceases to exist, or ceases to rule over a territory, and is replaced by another state, a succession occurs. One state has been substituted for another in sovereignty over territory and this complicates boundary claims.

The government of Pakistan claimed that as a successor state to British India, it derived full sovereignty over the frontier and its people and retained all rights and obligations of a successor state. The government of Afghanistan maintained that the line merely identified the areas in which the British and Afghan governments were responsible for controlling tribal peoples and that the Pushtuns of Pakistan should have the option of creating their own nation west of the Indus River. To this day, the plaza in front of the Presidential Palace in Kabul is called Pushtunistan Square. For an international lawyer trained in anthropology, the problem of the line was fertile terrain — raising issues of authoritative decision-making from tribal community to empire, of treaties and their interpretation, of unequal bargaining and the power of States — which ultimately I was able to explore in my doctoral dissertation, “Thinking Below the State”.

In the 1980s on the battlefields of Afghanistan, the Cold War was won. Now the West has left, leaving Afghanistan to the rest. I write this at the third anniversary of that departure, memorialized by veteran correspondent Ed Girardet, another habitué of the Durand Line.[2]

In 1934 the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society[3] carried the Obituary Notice of Sir Mortimer Durand, G.C.M.G., K.C.S.I., K.C.I.E, “dignified and courteous Director of the Royal Asiatic Society from 1911 to 1920”. Sir Mortimer, Ambassador to Spain and the United States of America, became a key figure in the Great Game by delimiting administrative and political boundaries between Afghanistan and the North-West Frontier of India. The announcement noted, “this achievement was crowned by a mission to Abdur Rahman, the great Amir of Afghanistan”. The line that bears Sir Mortimer’s name remains contested. Today it is less porous, separating misery on one side from suspicion and fear on the other. And from its 19th Century pronouncement to the present, is still studied by Afghan hands of the Royal Asiatic Society.

Charles H. Norchi

[1] Charles Norchi, Good Old Peshawar Days, 20 Crosslines Global Report, 29 (February –March 1996).

[2] Edward Girardet, Afghanistan: The Trump-Biden Debacle – Three years on, Global Geneva (15 August 2024), https://global-geneva.com/afghanistan-the-trump-biden-debacle-three-years-on/.

[3] Previously, Transactions of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, which commenced publication in 1831.