Sir Henry Rawlinson (Bart.) 1810-1895 was born into a middle-class family in Oxfordshire. Being the second son he could not expect an inheritance apart from his education. In 1827 he was sent, aged 17, to Bombay as a cadet in the East India Company’s army. He combined a sporting and adventurous nature with an interest in intellectual pursuits and a facility for languages.

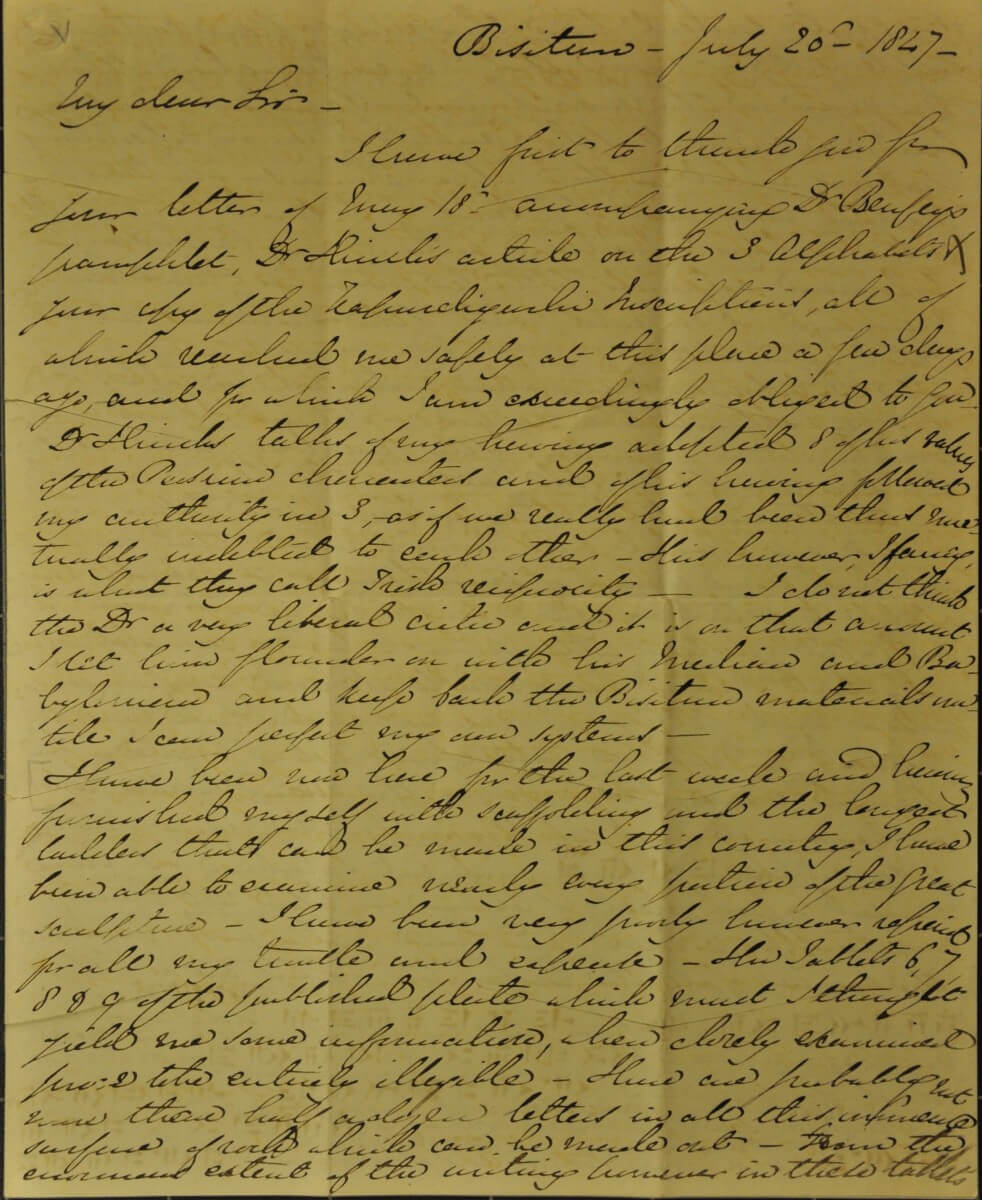

This combination earned him a place in a body of British troops sent in 1833 to Persia to train the Shah’s army. It was during his service in Persia that he saw the great trilingual cuneiform inscription of Darius the Great at Behistun (Bisitoun). He scaled the great rock face, made a copy of the Persian text and started his work on cuneiform decipherment. He also began his association with the Royal Asiatic Society.

The British troops were withdrawn from Persia in 1839 as a result of a change in Persian foreign policy, which brought his work on cuneiforms to an abrupt halt. In 1841 he joined the British military contingent in Afghanistan, where he was stationed at Kandahar as political agent (consul). When the Afghans rose against the British-backed ruler he was required to organise the defence of Kandahar, which he did successfully.

In 1842, on his return from Afghanistan, he lost most of his property and his papers when the boat in which they were being transported caught fire on the river Sutlej. Hence record of his early career and his early scholarly work is fragmentary, consisting mainly of material which he had sent back to Britain.

In 1843 he was posted to Baghdad as political agent (diplomatic relations with that part of the world being the responsibility of the East India Company). He remained at Baghdad until his retirement from the East India Company’s service in 1854. He resumed his work on cuneiform, concentrating on Assyrian and Babylonian and related languages – a much more difficult problem than Persian – but also supervising excavations on behalf of the British Museum.

He continued to work on cuneiform inscriptions for some years after his return and was regarded as the leading British authority, but became increasingly absorbed in political affairs (especially foreign policy). His involvement in cuneiform studies had ceased by the time he became a member of the Council for India in 1868.

A detailed list of the archive has been prepared by one of our volunteers. You can find it here.