Revisiting ‘Ancestral Worship’

This week, our blog features a post by Raymond Mann, exploring the background to one of the photos in our China Glass Slide collection. This photo was previously labelled ‘Ancestral Worship’, but as Raymond explains, the scene it depicts is much more complex than this might suggest.

The photograph forms part of a series of 199 images depicting topographical and architectural views and scenes of daily life, primarily across eastern China, from the 1880s – 1910s. This collection was catalogued and digitized by Dr Amy Matthewson in 2018/9, and the resulting images are available on the RAS Digital Library via https://royalasiaticcollections.org/photo-collection/. Dr Matthewson discusses this particular photograph in her article ‘The (Mis)Representation of Reality: “Knowledge” and Image-Making in Glass Lantern Slides of China’, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. 31 No. 2, April 2021, pp. 303-320. Now, we are pleased to welcome further analysis and discussion of this image, for which we are grateful to Raymond; and to Jamie Carstairs (Senior Digitisation Officer, University of Bristol), for arranging the post.

—

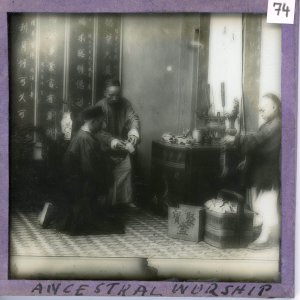

This photograph was historically labelled and catalogued as ‘Ancestral Worship’, but closer examination of the details makes the current title more appropriate: ‘Studio re-enactment of an opening ceremony for a Sze Yuen Ming (Yao Hua Studio) (耀華) photographic shop/studio, Shanghai’ (https://hpcbristol.net/visual/RA-m074).

The scene, which was obviously staged, depicts a man in formal clothing, kneeling in front of an altar with candles, joss sticks, and offerings. An assistant is pouring wine into a bow held by the kneeling man, for spilling on the floor in offering to his ancestors. So far this does seem to be ancestral worship.

However, the two banners flanking the altar, as well as those on the visible left wall had neither ancestral significance nor featured writings of ‘family rules’ 家規. They were all congratulatory banners for the opening of a new shop (see Note I, below, for an explanation of all the banners).

The youth in front has a string of firecrackers in his left hand, and a joss stick in his right for lighting the string to celebrate the occasion, something not usually seen in a sober scene dedicated to ancestral worship. A fire bowl, which was sometimes called a ‘treasure bowl’ 聚寶盆, is prominently labelled as such and placed there for burning paper money, which was in the shape of silver sycee 元寶 in the adjacent basket. The legend of the treasure bowl, which will multiply whatever is put inside, was a well-used metaphor for a profitable business.

Thus, while ancestral worship was part of almost any ceremony and holiday keeping, the theme here was to demonstrate the secular side of the culture, where money making was first in mind. Other than mammon-worship, the event was not very religious or spiritual. The man was shown just praying to his ancestors for help to get worldly money through his new business and, in return, sending (by burning) paper money, the underworld’s currency, to his ancestors.

The above interpretation would be natural for a person within the culture, but such pictures were also sold to Westerners. ‘Ancestral worship’ was what these customers saw, and according to some perspective the previous label on the slide was not incorrect. It was a matter of focus.

In fact, this postcard (https://bcc.lib.hkbu.edu.hk/artcollection/204-3-an21), that used the same picture, also labelled ‘ANCESTRAL WORSHIP’, concentrated on the worship part by cropping the image. So much of the banners were cut out that the names of the business and owner cannot be seen. Instead, a caption (see Note II) was added carrying a bit of religious zeal. The publisher of the postcard had a preferred view and desire to target customers.

Fortunately, in the RAS photo, another name of the studio owner, one which he used after venturing into selling medicine, can still be seen on a banner (see Note I). As the medicine business came after his initial studio but before his new one, it is very likely that he was depicting his new studio opening in 1905. Star Talbot, as Sze Yuen Ming 施圓明 , had a successful photography business, and as Sze Tak Chee 施德之 became very rich selling medicine, an innovative entrepreneur in the art trade, and a legend in his community. (See Note III.)

Additional Links:

[1] Image via University of Bristol Historical Photographs of China https://hpcbristol.net/visual/RA-m074

[2] ‘Ancestral Worship’ Postcard at Hong Kong Baptist University Library https://bcc.lib.hkbu.edu.hk/artcollection/204-3-an21

See here for Notes I, II, and III, including Raymond’s transcriptions of the banners and an account of Star Talbot’s life and career.

—

The catalogue reference for this image is RAS Glass Slide.01/(074), and it is also indexed at the University of Bristol Historical Photographs of China site as RA-m074 (https://hpcbristol.net/visual/RA-m074).

This collection of glass slide photos was donated to the Society by Mr D. B. Greene in 1982, and presented at a General Meeting of the Society on 10 February 1983, marked by a lecture from Mr J. F. Ford. For more details about the collection, see Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1983, No. 2, pp. 368-369, and Dr Amy Matthewson, ‘The (Mis)Representation of Reality: “Knowledge” and Image-Making in Glass Lantern Slides of China’, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, April 2021, Vol. 31 No. 2, pp. 303-320 (Fellows can login to read online here).