Nineveh on Screen

We are grateful to Amara Thornton and Michael McCluskey from the UCL, Filming Antiquity project for this week’s blogpost:

On Tuesday 26 January, the Director and staff of the Royal Asiatic Society welcomed us to introduce and screen some historic excavation footage in the Society’s archives. The footage dates from the late 1920s/early 1930s and shows excavations in Iraq at the mound of Kouyunjik, scenes in the village of Nebi Yunus, across the Khosr river from Kouyunjik within the ancient city boundaries of Nineveh, and scenes in the city of Mosul, across the river Tigris from Nineveh.

The footage (at present) has been attributed to Nineveh excavator Reginald Campbell Thompson (1876-1941), a British Assyriologist, epigrapher and archaeologist who had been excavating in Iraq on and off since 1904. Little is known about the film’s history to date, but research continues.

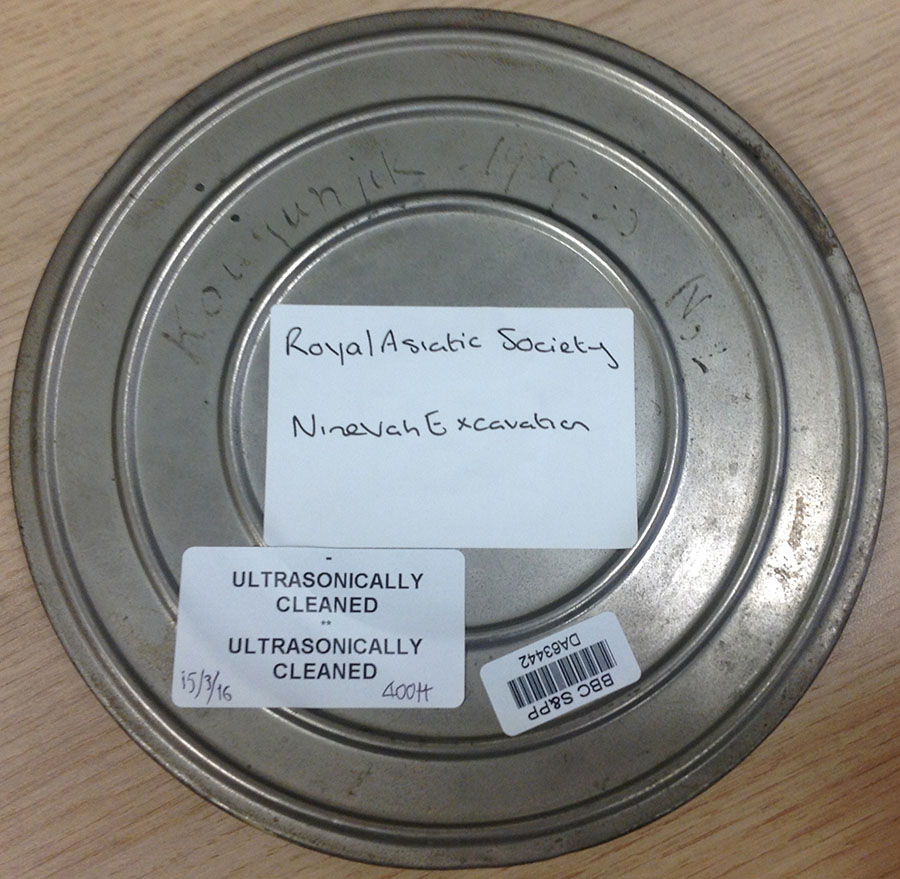

Our Filming Antiquity colleagues Ken Walton and Stuart Laidlaw had prepared a report on the film’s condition for the RAS in the 1990s, providing some basic technical information: the footage is on 2 reels of 16mm safety stock, black and white, and is silent. It was transferred to VHS subsequently and has now been re-digitised, but the RAS still holds the original film and canisters. One of the film canisters has the date 1929/1930.

Image 1(a+b): Two canisters of films containing footage from Reginald Campbell Thompson’s excavations at Nineveh in the late 1920s and early 1930s. One is marked “Kouyunjik 1929-30” while the other, labelled “Kouuynjik Nineveh Film 2”, bears the Campbell Thompsons’ address in Oxford. Courtesy of the Royal Asiatic Society.

As a young Assistant Keeper (2nd Class) in the Department of Assyriology and Egyptology at the British Museum, Campbell Thompson joined his BM colleague Leonard W. King on site at Nineveh in early 1904, remaining in Iraq for a year directing excavations at Nineveh. He returned to the site in 1927 to direct the British Museum’s renewed excavations there. The remains of the 9th century palace of the Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal were found during this productive initial season, leading Campbell Thompson to begin actively fundraising for a more intensive programme of work at the site.

Campbell Thompson directed four seasons at Nineveh – the initial 1927/28 season was followed by three in succession – 1929/30, 1930/31 and 1931/32. He focused on the mound of Kouyunjik, the location of Ashurnasirpal’s palace, and also sought evidence of a temple of the Assyrian goddess Ishtar, which was eventually discovered during the 1930/31 season.

Campbell Thompson’s wife Barbara joined him on site for all four seasons, credited in the official publications with her work on the “domestic” arrangements. A varied cast of team members included two friends of Barbara’s – Miss Isabel Shaw (1929/30) and Miss M. Hallett (1930/31) – as well as Richard Hutchinson (1929/30) and Robert W. Hamilton (1930/31) and Max Mallowan and Agatha Christie (1931/32). Of the Iraqi members of the excavation, Campbell Thompson specifically credited his overseers Yakub and Abd-el-Ahad, as well as Mejid Shaiya, whom Campbell Thompson referred to as “my old henchman”.

Although it is unclear at present whether the footage from Nineveh was ever publicly screened, it is clear that some care has been taken over the presentation. Impromptu title cards (no more formal than paper pinned up for the camera) lead viewers through a sequence of scenes. Reginald Campbell Thompson was intensely interested in the customs, culture and biographies of the people who worked with him and for him on site – this is clear in his war-time ‘memoir’ A Pilgrim’s Scrip, which charts his initial experience of Nineveh in 1904.

Image 2: A title card in the Nineveh footage, setting the scene for a sequence of potsherd washing where one of the washers is in need of (but does not have) a handkerchief.

Image 3: The two potsherd washers, whose names are unknown. Courtesy of the Royal Asiatic Society.

Campbell Thompson’s footage, if indeed he was behind the camera, offers scenes similar to other excavation films from this period and other, striking images unique to his own sense of the city of Mosul and its dynamism. Through the camera lens we see the work of the dig in the context of the local culture and geography. We see craft work, leisure activities, and what one intertitle describes as a fête complete with makeshift Ferris wheel.

Image 4: The ferris wheel, part of a local “fête”. Courtesy of the Royal Asiatic Society.

Other shots are more pedagogical and seemingly geared toward students: a scene shows the ‘squeeze’ process of transferring stone inscriptions onto paper and washing delicate pottery fragments. One interesting sequence shows off the different modes of transportation that intersect each day; crossing the screen we see a donkey drawing a carriage, a bicycle, and a motor car. This interest in different modes of transportation extends to the delicate process of ‘sending home’ items unearthed on the dig as we see workers ‘packing antiquities’ to be sent presumably to Britain. The note that these are being sent ‘home’ remind viewers that the filmmaker is not part of the local culture and that one result of the excavation work seen on screen is the removal of items from their local context to, perhaps, a display case in a British museum where films like this might have been screened to provide information about where these items came from and how they got to Britain.

Image 5: A screenshot from the sequence showing how to take a paper squeeze. Courtesy of the Royal Asiatic Society.

Image 6: Straw is being packed into wood crates in which antiquities will be placed for safe travel off site. Courtesy of the Royal Asiatic Society.

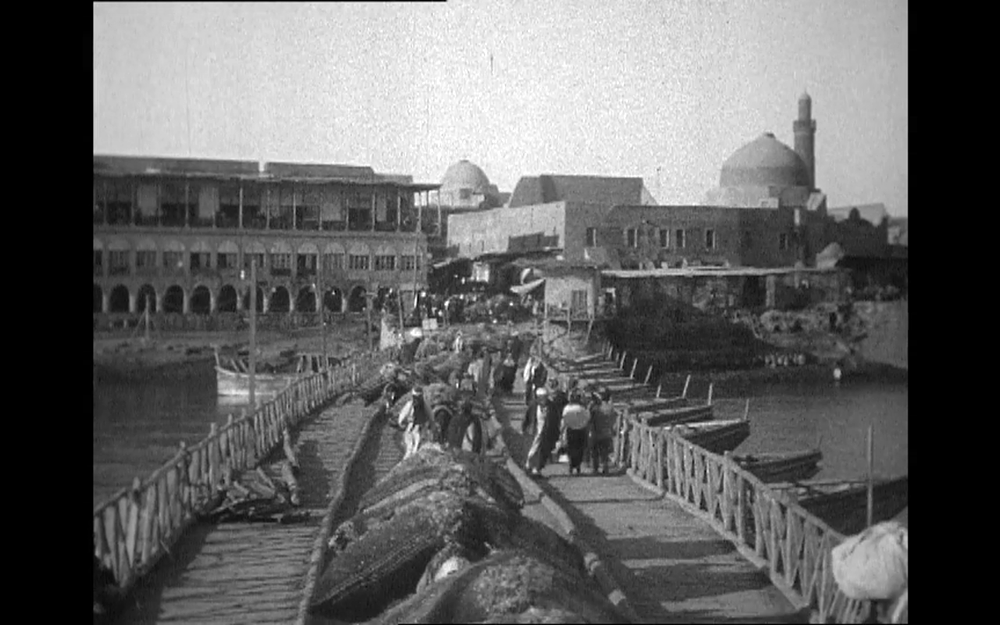

This footage also displays characteristics of the film and literature of the period. Its interest in the different rhythms on display in the city of Mosul align it with the ‘city symphonies’ of the late 1920s: films like Dziga Vertov’s The Man with a Movie Camera (1926), which celebrates the daily life of the urban environment and finds patterns amid the seemingly chaotic crowds. In Campbell Thompson’s film we see laundry workers, traders, the city’s infrastructure, and its mix of ancient and modern sites. The shot of crowds walking over a bridge into the city evokes the image captured by T. S. Eliot in The Waste Land:

‘Under the brown fog of a winter dawn/A crowd flowed over London Bridge’

as well as the work of Virginia Woolf who describes the crowds of workers that ‘sweep over the Strand and across Waterloo Bridge’. The shot of a Mosul bridge, then, seems part of a period interest in urban flow, especially how it positions the camera slightly apart, almost like city surveillance. His close interest in the city and the excavation help to preserve images of these places at particular moments in time and offer examples of film as ‘change mummified’, the definition of cinema given by French film theorist André Bazin.

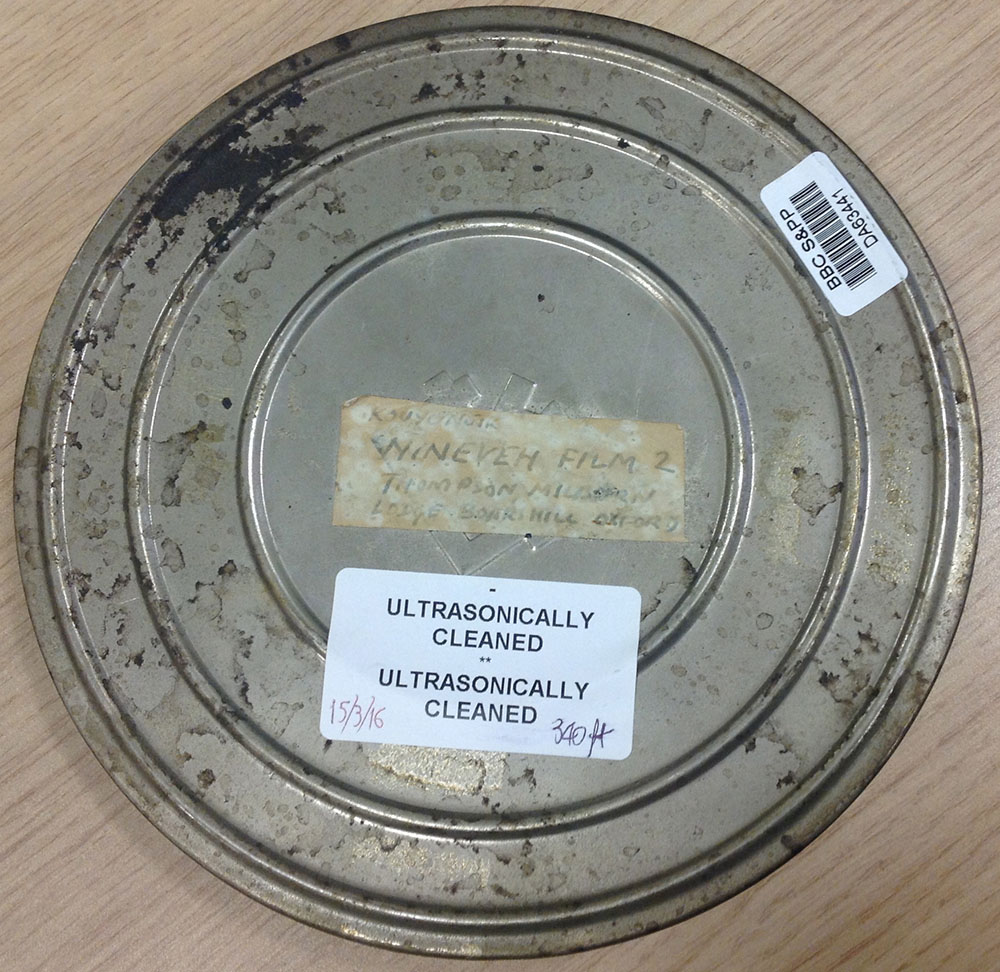

Image 7: A bridge to Mosul as captured in the Nineveh films. Courtesy of the Royal Asiatic Society.

It was a privilege to be able to show this footage at the Royal Asiatic Society in January, and thanks to our wonderful audience for their interest and comments. In the discussion after the screening we were very happy to hear from Perri Mahmood, who had the following insightful comments on the footage:

“As an Iraqi Kurdish by birth, I have been told about the history of the city of Mosul which was a multi-national city they were Kurds, Turk-mans and Arabs all lived together as Iraqi and proudly they enjoyed their heritages. But from mid sixties up to end of Saddam’s regime, the Arabisation program was continued because the city was one of the richest city for oil, all other ethnic minorities specially Kurds were pushed out from the city and forced to settle in another part of the country and brought Arabs from south of the country to settle in Mosul. But what I saw that night was the power of an archive of historical material, now I saw those images, and I know what we were told was true. I could see and recognize that the traditional clothes they were wearing were different. Thanks again for people like you and your team we can always see what an effort people made in the past for us now and for the future generation.”

A special thanks from us to Perri and all those who have given us feedback on the films, and also to Nancy Charley, Ed Weech and Alison Ohta from the Royal Asiatic Society for welcoming us as researchers and allowing us to screen this wonderful footage and include shots of it in this blog. Further details on Filming Antiquity can be found at http://www.filmingantiquity.com. We are also on Twitter @FilmAntiquity.

References/Further Reading

Campbell Thompson, R. & Hutchinson R. 1929. A Century of Excavation at Nineveh. London: Luzac & Co.

Campbell Thompson, R. & Hutchinson R. 1931. The Site of the Palace of Ashurnasirpal at Nineveh, excavated in 1929-30 on behalf of the British Museum. Liverpool Annals of Archaeology and Anthropology 18: 79-112.

Campbell Thompson, R. & Hamilton R. W. 1932. The British Museum Excavation on the Temple of Ishtar at Nineveh, 1930-31. Liverpool Annals of Archaeology and Anthropology 19: 55-116.

Campbell Thompson, R. & Mallowan, M. E. L. 1933. The British Museum Excavation at Nineveh, 1931-32. Liverpool Annals of Archaeology and Anthropology 20: 71-186.