News of the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society

We start this week’s blog post with a message from Charlotte de Blois, Executive and Reviews Editor of our Journal, busy working from her home in Cambridge:

The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society has been published, uninterrupted, for almost 200 years. Even during the First and Second World Wars, the journal maintained its publication.

The last few weeks have been extraordinary for everyone. We have all become subject to new limitations and are also compelled to find new ways to problem solve. That said, most of us have been adapting to sudden and constant change over several years now and thus we are getting adept at meeting its demands. This is true for people working in academic publishing as much as it is for people working in other industries and, of course, change continues for those working on the Society’s Journal. This week’s blog post provides an opportunity to briefly summarise some of our 21st century developments.

Since the early 1990s the JRAS has been published in partnership with Cambridge University Press. This was an arrangement organised by the late Professor David Morgan, our former editor, and Mr Peter Collin, an active member of the Society who has served on the Publications Committee for many years. Over the last two decades there has been a shift in production and editorial procedure from an era defined by paper submissions and mechanical typesetting to one characterised by electronic submission and electronic typesetting. And change is continuing to happen.

Some 10 years ago, the concept of Open access led to new initiatives concerning the monetisation of academic publishing. Open access is a set of principles and practices through which research outputs are distributed online, free of cost, and diminishing other access barriers. Supported by the UK and other governments, it allows for government-funded research to receive grants to help cover the costs of publication as long as the published material is made freely available to readers. There are of course clear benefits to this, some of which we may well be reaping at the moment. For example medical studies can be published online, in designated repositories, as soon as they are completed. This may avoid repetition of research and enable professional scrutiny and incorporation into best practice to happen speedily. Peer-reviewed material can also be published through open access. The attempts to understand Coronavirus have been aided by this revolution in academic publishing.

Publishing in the arts and humanities differs in some ways from publishing in the sciences. Cambridge University Press is committed to continuing support for the humanities and social sciences. A key part of their strategy is to ensure that the availability of research in those subjects is easily accessible electronically all over the world. JRAS is part of a distinguished package of CUP Journals dealing with the study of Asia.

As the journal of a learned society with a learned but diverse fellowship, the JRAS has more readers of its print version than most of its sibling journals in Cambridge University Press’s package. Those Fellows who love to have their nose in a book rather than eyes glued to a screen can be reassured that the Press will catch up with print issues, hopefully later this year, when it is feasible to do so. The Editorial Board hope that Fellows will continue to enjoy new articles and reviews as they come out online. All articles once they are accepted, edited and typeset are displayed on FirstView at Cambridge Core. Details on how to log in to the read the journal are at this link. Here you will find articles displayed separately, not gathered into issues, but the material is there.

We would also like to stress that we are still eager to receive good quality submissions through our automated tool ScholarOne.

And post-crisis, there will still be two ways to access the Journal:

Thank you to Charlotte for providing this information for the blog post. The Journal for January 2020 is now available and this includes an obituary for Professor David Morgan, expert on the Mongols and, as mentioned above, head of the Journal’s Editorial Board for many years, who died in April 2019. The articles in this issue concern the influence of the Mandarin Union Version of the Chinese Bible and is guest edited by George Kam Wah Mak. Dr Mak gave a lecture to the Society on the Protestant Bible in 2015. This is still available to listen to via Backdoor Broadcasting.

And while Charlotte is busy working in Cambridge, I am beavering away in Ashford, Kent. For the foreseeable future I will have to shift my work hours around, hence the blog at the early part of the week, as for some hours, Weds- Fri, I will be caring for my granddaughters. Both their parents are still working, my daughter having just returned to work as a senior physiotherapist after recovering from a Covid-like illness (having been contracted before testing we remain unsure whether it was or not). Last week, during some of my work hours, I completed the catalogue for the Papers of the Gibb Memorial Trust. I’ll write more about those in a forthcoming blog as they are worthy of more space. I’ve also begun editing another list in preparation for cataloguing. This was prepared by one of our volunteers, Ian Scholey, and my thanks go to him for his dedicated work on various projects with the archive collections. This list consists of over 500 letters which had been copied into a handwritten volume covering the date period from 1823-1861.

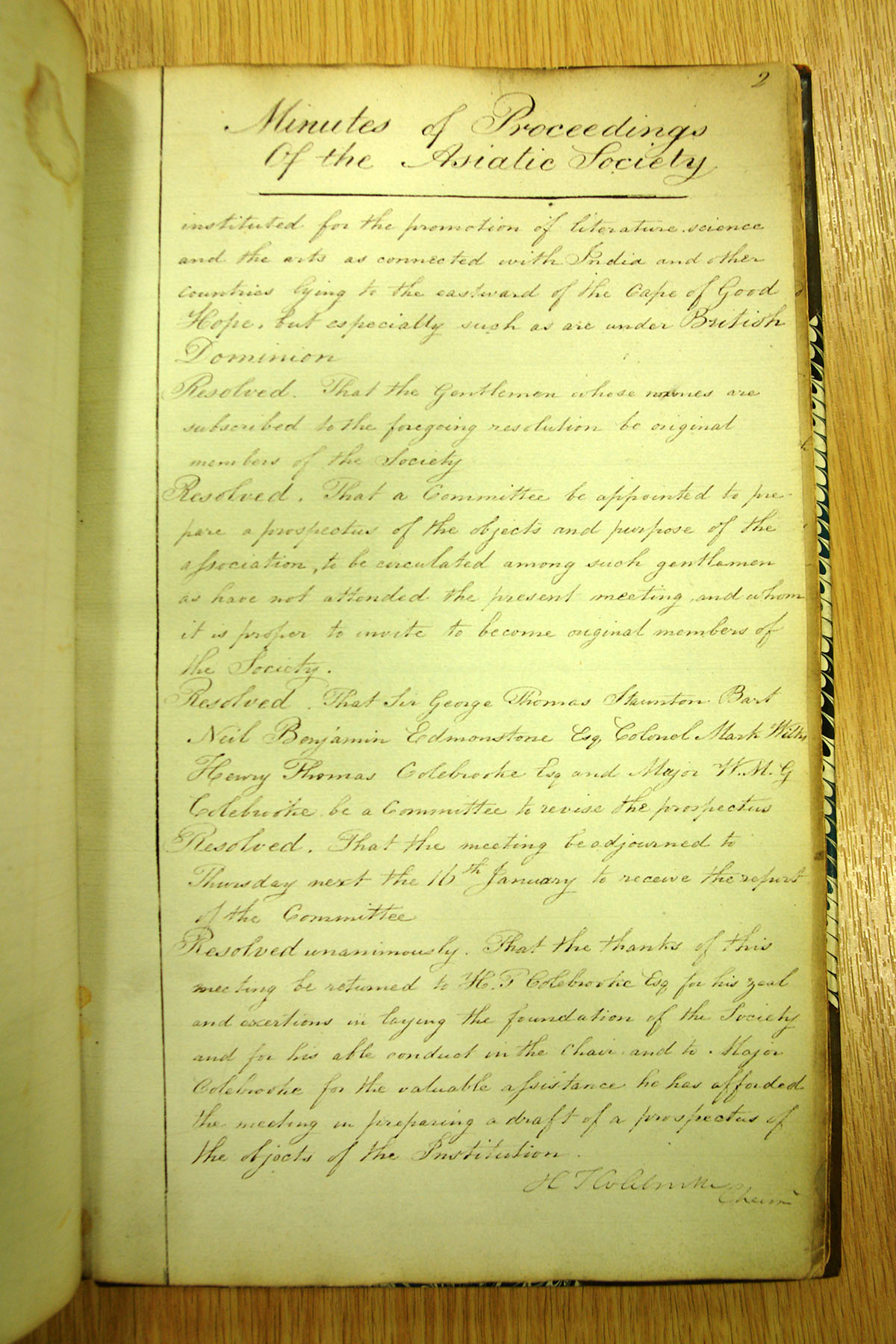

These letters are all business correspondence of the Society and so are an important record of its early activities. The earlier ones, covering 1823-1835, are all concerned with the finances of the Society. There is then a break in the letters until 1846, after which the correspondence covers a broader spectrum of activities. It makes me suspect that initially the book was just to cover the finance correspondence. This then was not maintained and some time later the book was rediscovered and put to use again but to record all correspondence deemed necessary for retention. Unfortunately, I don’t have a picture of the volume but it is in a similar style to the early Minute books, one of which is pictured below:

Of course, I will not be able to put the catalogue online until I can check the entries against the volume after we have returned to the Society’s premises, but 500 letters means 500 catalogue entries – plenty, alongside my other projects, to keep me busy for a while.