Manning and Marshman work together on Chinese translation

In 1810 Thomas Manning was in India. We know from a letter to his father, William Manning, Rector at Diss, Norfolk, that he sailed on board the Pellen from Canton to Bengal (letter postmarked London 18th July 1810). Manning wanted to find his way into the interior of China and had decided upon trying to head up through India into Tibet to reach China overland. However he was stuck in India waiting for permission to proceed.

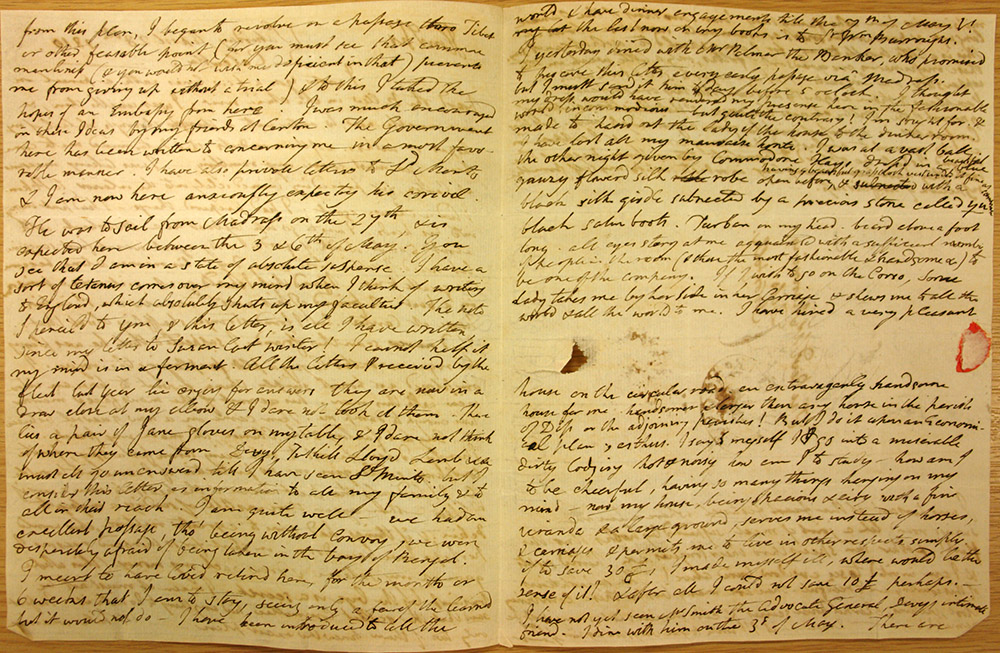

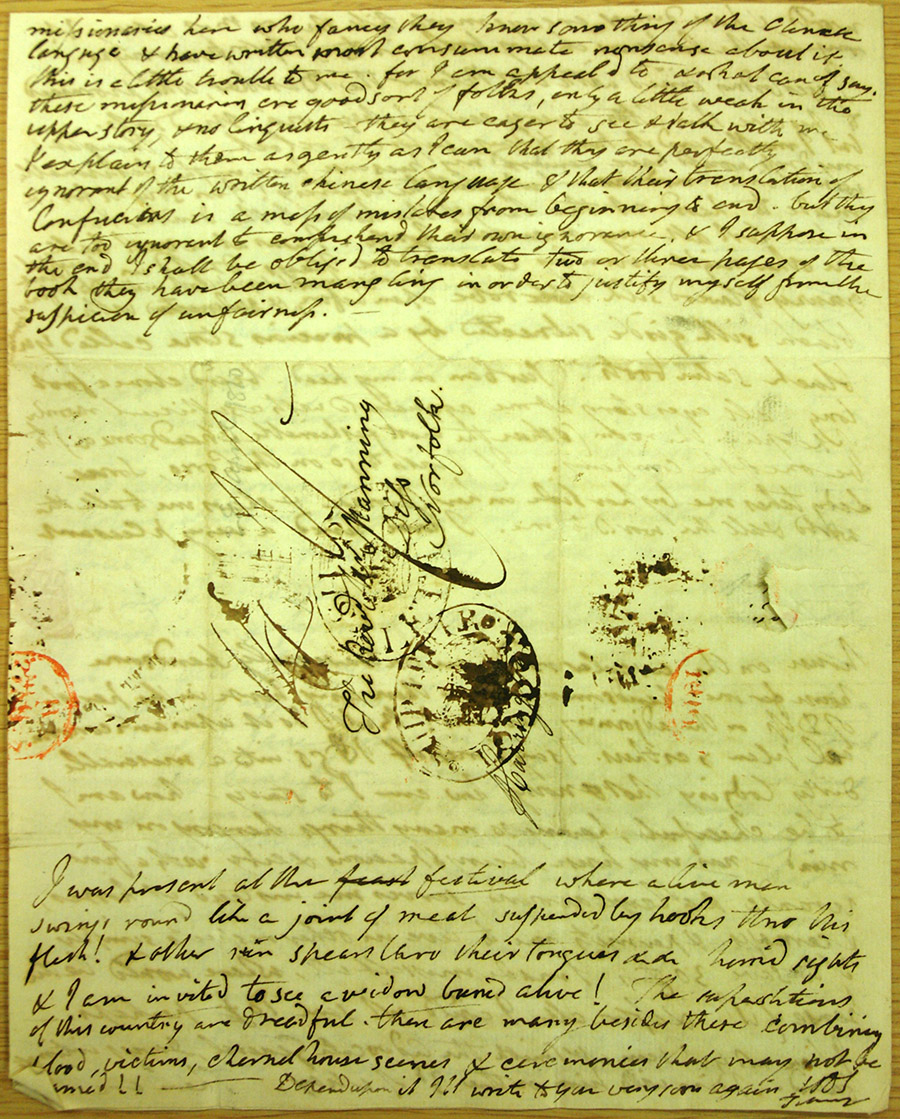

Two further letters to his father tell of something of his plans. In the first he writes of his frustrated attempts to get to Pekin whilst in Canton giving some of the reasons why it could not be accomplished. The suggestion has been made that he should try to go via Tibet and letters have been sent for him and he has other private letters with him. He had a good passage on the Pellen though they were without convoy and therefore fearful of being taken by the French in the Bay of Bengal. He has numerous dinner invitations including to Sir William Burroughs. He dined the previous evening with Mr Palmar, the Banker. Manning had: “Turban on his head, beard over a foot long. All eyes staring at me”. He had rented a spacious house on the circular road and justified it by claiming it is necessary so he stays healthy and can study.

In the second Manning is hoping to enter Tibet as a trader and has sent for goods from Calcutta. He is living with an Indian family in Rajpur and describes the earth floor and bamboo mat walls. He is pursuing trains of thought on language study but is yet unable to prove his ideas. He writes his thoughts about language, man’s deeds and religion. This is dated 20th December 1810.

Manning also writes, in the first letter, that there are “missionaries in Calcutta who claim to know something of the Chinese language but they have it wrong”, “their translations of Confucius are map of mistakes”. He, perhaps judiciously, does not name any names but interestingly within the Manning Archive here at the RAS, there are eight letters to Manning from Joshua Marshman.

Joshua Marshman (1768-1837) was one of the Serampore Trio who founded Serampore College in 1818 – the other two being William Carey and William Ward. However Marshman had first arrived in India in October 1799 and had been involved in translating both the Bible and classical Indian literature. He was also keen to translate the Bible into Chinese and in 1814 produced “Elements of Chinese grammar: with a preliminary dissertation on the characters, and the colloquial medium of the Chinese, and an appendix containing the Tahyoh of Confucius with a translation” – an interesting connection!

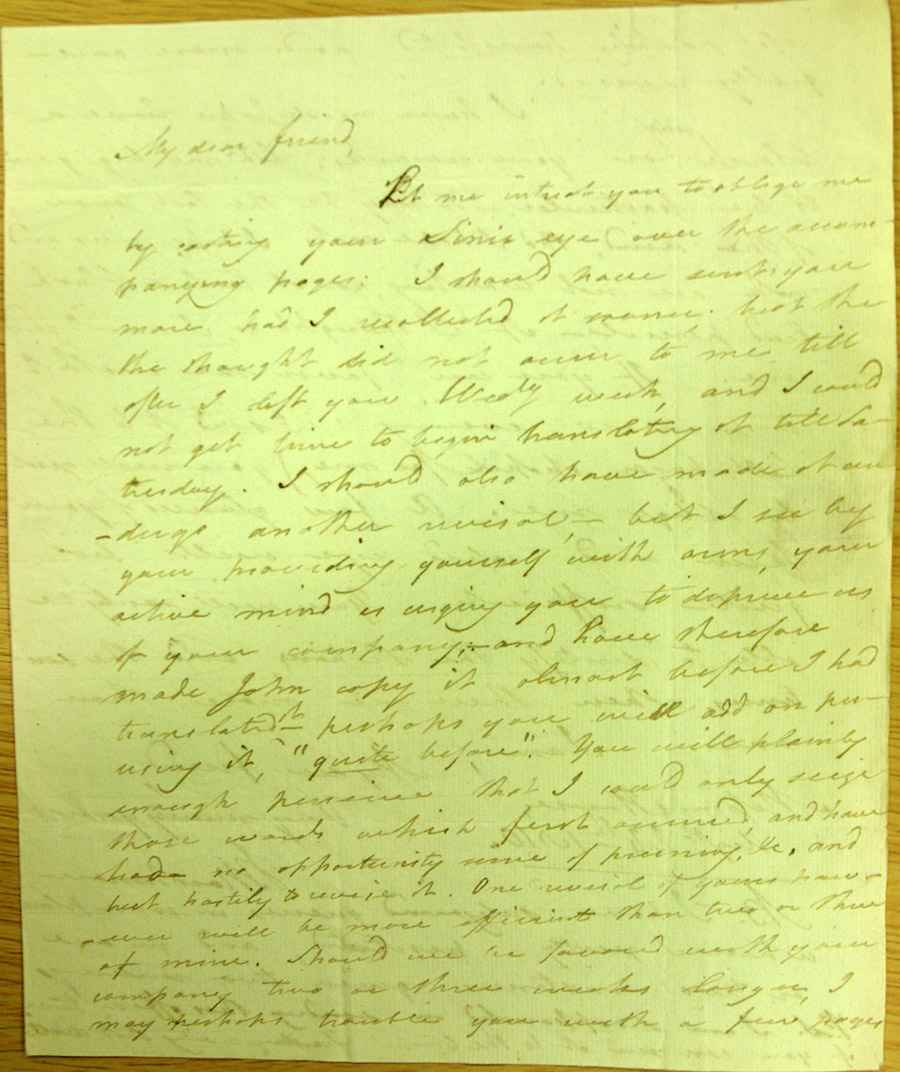

The letters from Marshman, all sent in 1810, show that Manning is helping Marshman with his translations. Marshman would send a copy of his manuscript to Manning written in such a way that each side of text would have a blank page facing it. This was for Manning’s annotations. He also sent him a copy of Matthew’s Gospel in Chinese, “almost wet from the binders”. It seems that Manning was very active in helping make the text more accurate. From the letters it is not possible to tell whether the manuscripts that Marshman was sending were part of his Chinese grammar or Bible translations – Manning’s letter to his father might suggest the former.

Marshman appears to be very grateful for Manning’s help and he also tries to use his influence to help Manning – talking to Lord Minto on his behalf, discussing his situation with William Carey, and informing Manning of other Englishmen who were heading to North India who might be of assistance. He also sends his Lectionary to Manning and asks that Manning sends his to Marshman so that he can have a new binding put on it.

The archive here does not contain any further correspondence between them, once Manning begins his travels, so we cannot know whether the collaboration continued. I have contacted the Angus Library and Archive at Regent’s Park College, Oxford, who hold a Joshua Marshman archive. Unfortunately it does not contain any correspondence between the two men. But these few letters give us some interesting insights into the lives of these early pioneering translators. I am hopeful that as I continue to prepare the Manning archive for cataloguing that further connections and revelations will be found.