‘Knowledge’ and Image-Making in Glass Lantern Slides of China

Journal Update:

We are pleased to announce that the April issue of the Society’s journal is available for Fellows to view on Cambridge Core, with its print companion being received by subscribers at the end of last week. As you can see from the contents page below, there are eight individual articles on very different topics. However, some of the ideas elaborated show a link around historical translations, definitions, representations and misrepresentations.

Article by Dr. Amy Matthewson:

Dr. Amy Matthewson (Research Associate: SOAS) has kindly shared with us her experiences in working with the Society’s collection of Chinese glass lantern slides. Her engagement with this collection has formed the basis of an article that is included in the most recent edition of the journal and is titled: ‘The (Mis)Representation of Reality: ‘Knowledge’ and Image-Making in Glass Lantern Slides of China’.

The Royal Asiatic Society (RAS) of London houses a collection of 200 glass lantern slides of China depicting a diverse range of topics such as buildings of architectural significance , topographical features, famous historical figures as well as a variety of daily activities. My time with this collection was spent cataloguing and digitising the slides, which you can view here. I also used the University of Bristol’s ‘Historical Photographs of China’ to research some of the photographs and became a member of The Magic Lantern Society to access more information on lantern slides.

There is only one record that possibly tells us where and when the collection arrived at the RAS. The document notes a donation by Mr. D.B. Greene of a collection of glass lantern slides of China to the RAS in London in 1982. The record is very brief and raises more questions than answers. How and when were they used? Were there lectures, maps, or other forms of illustrations that originally accompanied the collection? Was this the entire collection? Were there any other slides in the collection that had been removed, discarded, or destroyed? If so, which ones and why? An inspection of the images on the glass slides only adds to the series of queries. There is no information on who the photographers were, when the photographs were taken, when they were transformed into lantern slides by whom and for what purpose, nor how they were acquired or circulated.

What is certain is that the collection consists of reproductions of photographs taken at varying times by different photographers and that lantern slides were at the height of popularity in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries before their eventual demise with the advent of cinema. With this information along with dates of known photographs, we can place the collection as being created during the Victorian and Edwardian eras.

The late nineteenth century converted almost every topic and theme into lantern slides. The popularity of this visual media gave rise to professional showmen who used lantern slide shows to entertain a broad audience with elaborate performances accompanied by musicians and sound effects. Improvements were made to light sources with the use of hydrogen limelight and Arc light thereby dramatically changing the quality of the visuals on display. Some of the more extraordinary shows were performed at the Royal Polytechnic Institution at 309 Regent Street in London and featured screens that were approximately 25 feet across.

Lantern slide shows were not solely for entertainment, they were used for education as well as propaganda purposes. The Royal Geographical Society (RGS) was an avid user of this visual technology when promoting geographical education alongside exploration. It became common practice for experts and specialists to use lantern slides to illustrate their lectures. The RGS once held as many as 40,000 lantern slides, predominantly of maps, diagrams, figurative and landscape photographs. The Colonial Office Visual Instruction Committee (COVIC) developed projects to instruct British and colonial children about Empire and the ‘Mother Country’, with the widespread use of lantern slides. British manufacturers of lantern slides established a standard size of 3.25 inches square, which matches that of the lantern slides in the RAS collection.

As a researcher of visual and material cultures, a fascinating aspect of these glass slides is the physical traces of human interaction. For example, some of the slides underwent recent conservation. A light grey coloured tape replaced the old blue gummed paper that bound the glass slides together, giving this group of slides the appearance of newness. Unfortunately, this resulted in the removal of the original captions on some slides. The elimination of these handwritten texts evoke a sense of potential loss of the past, a connection severed with this new, fresh, and modern replacement.

The individual glass slides had also been stored in various ways. Some of the slides were individually wrapped in photographic conservation paper while others were placed inside chemically-free plastic pockets. In the first group, each slide had been carefully placed inside acid-free paper which had been specially cut to wrap around and protect the glass slide. Due to the non-transparent nature of the paper, the number of the slide and its brief caption had been written on the front of the paper packet. As part of my work on this collection, I removed all the slides from their original boxes and rehoused them in photographic conservation boxes for extra protection against dirt, dust, and light.

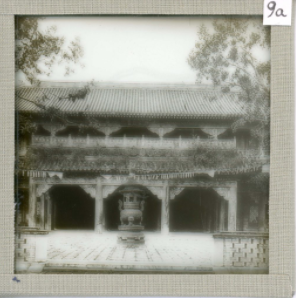

The labelling of each lantern slide also caught my attention as it indicated the ways in which photographs of different cultures are viewed and (mis)understood. Some of the images had been bound back to front flipping the Chinese characters captured in the photograph. The captions use an old-fashion system of romanisation for Mandarin instead of the modern system of pinyin. I also noted that while the collection is numbered from 1 to 199, there is a 9a and 9b which are both titled the ‘Temple of Heaven’ and thus labelled (a) and (b). Perhaps the original intention was to group these two photographs together.

I am grateful to the RAS, Nancy Charley, and Edward Weech for the opportunity to engage with this collection, which resulted in my Open House talk on 26 March 2019. I also wrote up my research in an article “The (Mis)Representation of Reality: ‘Knowledge’ and Image-Making in Glass Lantern Slides of China”, published in the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Volume 31, Issue 2, April 2021, pp. 303-319. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S135618631900052X

Dr. Amy Matthewson

amymatthewson.com

Twitter @Visual_Cultures

We would like to thank Dr. Amy Matthewson for contributing to this week’s blog post and her article can be found on First View for subscribers of the journal.