Conserving and Celebrating our Burmese Collections

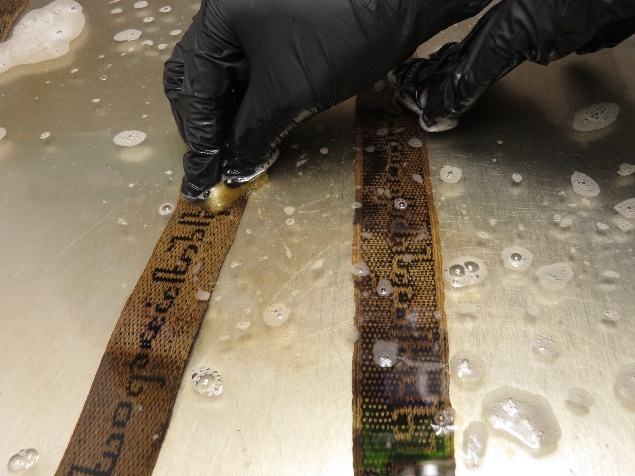

Earlier this week, the Society hosted a small event to commemorate the conservation of one of its manuscripts. This is a Kammavācā, a Pali term which means “an assemblage of passages from the Tipitaka […] that relate to ordination, the bestowing of robes, and other rituals of monastic life” (for more information, see here). This manuscript (RAS Burmese 86) is particularly notable because it includes a sazigyo, a type of woven braid used to tie manuscripts. Both the sazigyo and the manuscript’s brightly-coloured cover were conserved earlier this summer, thanks to the generous donations of the Society’s members and supporters. We were grateful to the conservator, Jessica Burgess, from Janie Lightfoot Textiles, for coming to give us a talk about the conservation process and the long-term considerations when looking after such objects.

Our appeal for help to conserve this manuscript received a wonderful response, a special example of the consistent support that the Society relies upon and which makes our work possible. Independent learned societies like the RAS have played an important role in British society for many years, providing a genuinely independent space for people to pursue ideas and exchange knowledge. Over the centuries, such independent associations have helped keep alive the spirit of free inquiry, and have helped ensure the continuity of our history and culture across the generations. But they can only do this because of the generosity of individuals.

Like most learned societies, the RAS receives no direct state support, and so it benefits very directly from donations of money. But the present and future of the Society also depend upon the donation of time, labour, and expertise, as well as the donation of things. People give their time to help administer the Society, running and serving on Council and Committees to provide the necessary oversight and direction for our day-to-day work. And volunteers help us do so much more with our collections and activities than we would otherwise, particularly in the fields of cataloguing and book repair. We also continue to benefit from donations of cultural heritage, keeping alive the noble tradition which formed the Society’s collections in the first place. Recent donations include the Library and Archive of the Sinologist A.C. Graham, which was donated in 2018 by Dawn Baker and the Graham Baker family. And earlier this summer, a portrait of Stuart Simmonds was donated by Greg Day, the nephew of Professor Simmonds’ wife, Patricia. Stuart Simmonds was Professor of the Languages and Literatures of South East Asia, RAS President from 1973-6, and played a leading role in the Society for many years.

Including over 100 manuscripts in total, the Society’s Burmese collections are one of its largest, but also one of its least understood. Several of our manuscript collections came from a single source, such as the Raffles, Hodgson, Whish, and Tod collections; compiled and studied by Orientalist scholars, these collections therefore arrived with a reasonably comprehensive body of provenance and other information which in modern parlance we might term “metadata”. By contrast, the Burmese manuscripts came from a variety of donors right from the earliest days of the Society up until the First World War. In many cases, the manuscripts were accessioned with scarce details about their subject and contents. Our largest collection, the Persian manuscripts, came, like our Burmese holdings, from a multitude of sources, but our knowledge and documentation of the Persian manuscripts is fairly advanced because they have attracted so much sustained interest and scholarly attention over the centuries. The Burmese manuscripts have attracted comparatively little study in recent years, and so the state of our knowledge about this collection is less complete. Most date from the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, though a few are from the seventeenth century.

Jacqueline Filliozat made by far the most comprehensive survey of the Burmese manuscript collection, resulting in the invaluable “Survey of the Pali Manuscript Collection in the Royal Asiatic Society”, which was published in the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society in 1999. As the title suggests, Filliozat’s chief concern was with manuscripts in Pali, which is the sacred language of Theravada Buddhism. Filliozat noted that manuscripts often entered the collection with little or no explanatory information. Nevertheless, there was clearly sufficient interest in manuscripts from Burma and the surrounding regions in the early nineteenth century that people started donating them to the Society as early as 1825. One obvious reason for this was that Pali manuscripts were a valuable source of information about the religion of Buddhism, whose Indian origins were a subject of growing interest to Europeans at that time. But the early acquisitions also reveal one of the characteristic features of the Burmese collection, which is the remarkable variety of media on which the sacred texts were recorded. This is one of the great attributes of the Burmese collection, but it also presents significant conservation challenges. In addition to works on palm leaf, early donations included manuscripts on cadjang leaf and even textiles, with writing in mother-of-pearl; and manuscripts on a variety of leaves, including copper, and lacquered, silvered, and gilt leaves.

The background to the acquisition of Burmese manuscripts by British people at this time was, of course, the significant increase in British contacts with Burma in the early nineteenth century. Great Britain had political and commercial dealings with Burma in the eighteenth century, as the East India Company became more involved in administering parts of the Indian subcontinent. Burma had expanded its territories westward in the late eighteenth century, bringing it into close proximity to the Company’s territories in Bengal. But British knowledge about Burma expanded considerably in the nineteenth century, especially after the First Anglo-Burmese War of 1824-1826. Afterwards, the Burmese Empire was much reduced by a loss of territory and the payment of a large indemnity. The whole of Burma was made part of British India in 1886 after the Third Anglo-Burmese War, and (excepting the period of Japanese occupation during the Second World War) it remained a part of British India until independence in 1948.

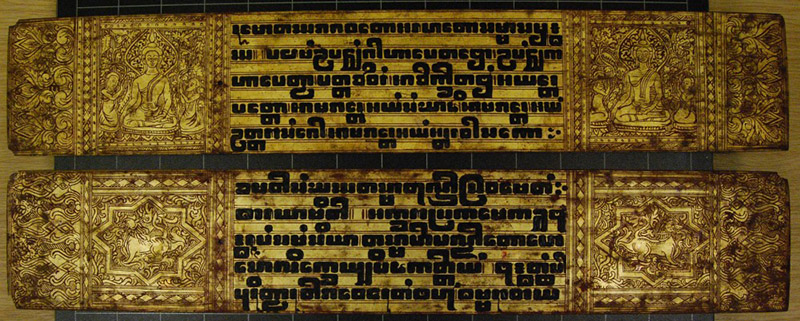

Kammavācā manuscripts have long been one of the most popular genres for Western collectors of Burmese texts, and as such they are quite well represented in Western collections. Created in 1792, the Kammavācā that was conserved in this project comprises 11 dark red lacquered, gilt, and decorated plates. The plates are contained within two light wooden covers, and wrapped in a multi-coloured cotton cloth woven with bamboo slats. One of the reasons it stands out – in addition to its intrinsic beauty – is that it is accompanied by a sazigyo, which is a woven band used for binding manuscripts. This sazigyo is a particularly early example of this rare and distinctive art form, with a brown background. The Society realized it needed conservation due to the fact that both the cover and, especially, the sazigyo suffered from abrasions and damage from age and historic usage. The initiative for the project came from the late Ralph Isaacs, and we are pleased to think that the completion of this project adds to the legacy of Ralph’s work researching, documenting and promoting the history of this artistic tradition.

There is no information about how this particular manuscript entered the Society’s collections, but it was likely donated during the nineteenth century as were most of the Burmese manuscripts. Most of these manuscripts were donated by scholars, travellers, and officials and soldiers associated with the East India Company or Indian Civil Service. The notable exception to this pattern is the Morris Collection, which the Society bought in 1896 following the death of Richard Morris (1833-1894), a self-taught philologist who was a schoolteacher and Anglican clergyman. Morris is chiefly known for his work on the early English language, in which he sought to apply the methods of classical philology to early English texts, producing new standard editions of authors including Geoffrey Chaucer and Edmund Spenser. He also published educational works on English grammar before eventually turning to the study of Pali. This interest developed in consequence of his friendship with Thomas Rhys Davids, who was Secretary of the Royal Asiatic Society between 1888 and 1904. Rhys Davids was also the founder of the Pali Text Society, which became the world’s foremost publisher of Pali texts. The Pali Text Society was itself inspired by the model of the Early English Text Society, which had the fine aim of making the early works of the English literary inheritance available to a popular audience. Morris edited several Pali texts for the Society during the 1880s. This episode is a fascinating example of how interest in Asiatic religious and literary traditions could help inform British intellectual culture, in this case in a remarkably erudite and serious-minded way. The Morris Collection comprises 38 items, mostly in Pali, with a few items in Sinhalese and Burmese, as well as various Pali transcripts in Roman characters.

The Society also has a small but important collection of Burmese art. The collection of James Low contains drawings of Burmese scenes by Low and by an artist who has been identified as a Chinese or Thai man called Boon Khon. Made around 1825, these were intended for Low’s History of Tennasserim, but were never published. There is also the Unwin Collection, which comprise 45 watercolours and drawings of Burma, India and Egypt made by Arthur Hamilton Unwin (1840?-1905?) and his wife in the late nineteenth century. There is also the beautiful painting of the Palace of the King of Ava, which was made in 1832 for Henry Burney, who was British Resident, by order of the King of Ava. We also have three very expressive paintings of King Thibaw and his wives, which were donated in 1880 by William Judson Addis.

This year has seen a significant boost to the profile and accessibility of the Society’s Burmese collections. This summer, the Internet Archive completed a project to digitize all the Society’s palm leaf manuscripts, which includes the majority of manuscripts in our Burmese and Morris Collections. In all, 400 manuscripts were digitized under this project – 20% of the Society’s manuscript holdings – and these can now be viewed from anywhere in the world with an internet connection, absolutely free. This should make it much easier for people to see these manuscripts who might not be able to visit the Society in person. We hope that the enhanced accessibility of these collections helps to inspire new research, and simply makes it easier for people to enjoy them from the comfort of their own home.

Over the coming months, we plan to add digital copies of these palm leaf manuscripts to the Society’s own Digital Library, which was set up last year thanks to support from the Friends of the National Libraries. Just like the conservation of our Kammavācā and its sazigyo, these are the kind of projects that can be made possible by the support and partnership of individuals, charities, and other organizations. We hope to build on these achievements as we work towards the Society’s bi-centenary in 2023, as we look towards the future and renew our mission: promoting research, knowledge and interest in the history and cultures of Asia, as well as awareness of how British people over the centuries have learned about and been inspired by Asia.

Next week, the Society’s programme of events continues on Thursday 10 October with a free public lecture by Dr Bo Gao (University of Nottingham, Ningbo, China) entitled “Economic Cooperation between China and DPRK, Past and Present”. We hope you will be able to join us then.