Chinese Tiger Lore through Folk Prints (David Leffman guest post)

This weeks blog post comes courtesy of David Leffman who gave a presentation on Chinese wood blocks to the Society in June, the recording of which is now available on YouTube:

For more on David’s work please visit his website at www.davidleffman.com

This blog post provides an opportunity to discuss two long-time interests: investigating Chinese culture by studying traditional woodblock prints, which I have been collecting since the early 1990s; and folklore about tigers.

Woodblock printing was invented in China at some point before the seventh century to manufacture Buddhist texts as religious talismans. At some point pictures were added and eventually began to be made for their own sake, initially for worshiping the thousands of Chinese folk gods. An industry mass-producing these images for popular use established itself during the Song dynasty (960–1279), branching out from religion into narrative and moral scenes and, finally, largely decorative images for home use. By the early nineteenth century the country must have been awash with paper, as workshops in cities, towns and villages around China pumped out literally hundreds of millions of these folk prints every year.

Printing woodblocks at Zhuxian town

By the 1900s however, commercial woodblock printing was beginning to be undermined by faster, cheaper mechanical processes such as lithography, and – following a period of civil wars, foreign invasions and adverse political ideologies – had become virtually extinct by the 1980s. China’s remaining woodblock studios have generally repositioned themselves as folk craft museums, and their production volumes are very small-scale compared with a century ago.

Never considered fine art or intended to last long, these folk prints were made on cheap, tissue-thin paper and often exposed to the elements on the outside of buildings, or were even deliberately burned. Despite the vast quantities once made, comparatively few antique examples survive today.

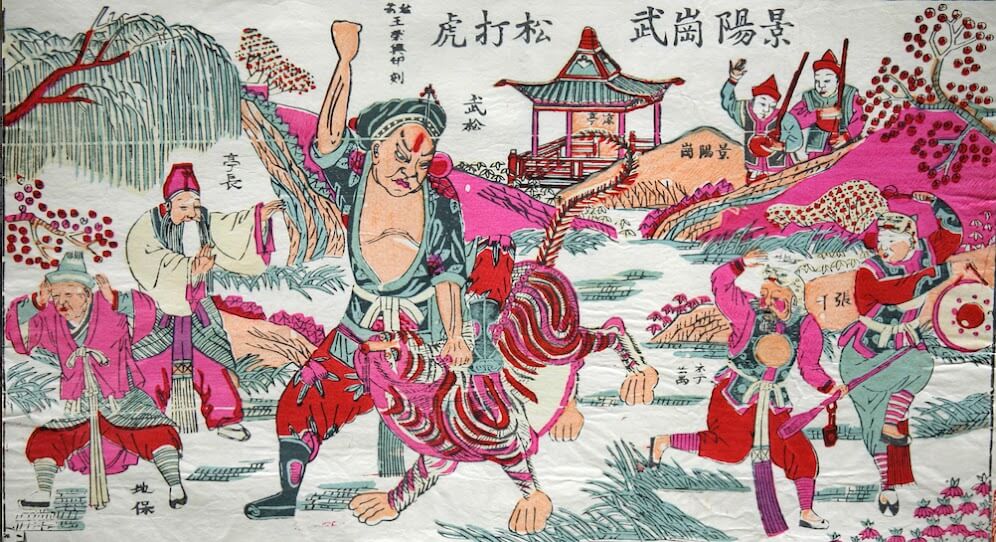

For their part tigers were also fairly common in rural China until about a century ago, at times posing a real danger to human life. The Ming-dynasty vernacular novel Outlaws of the Marsh (also translated as All Men Are Brothers and The Water Margin) features several episodes where the tale’s rebel heroes manage to defeat man-eating tigers with their bare hands – the near-impossibility of this underlining their own superhuman abilities.

“Wu Song Beats the Tiger”, from Outlaws of the Marsh

In folk art, this strength and ferocity also made tigers popular guardian symbols, and children were dressed up in tiger shoes and hats to frighten off the evil spirits which were believed to cause childhood diseases. There’s wordplay here too; the character 虎 for tiger sounds similar to護, meaning “to protect”. Beyond this aspect tigers also serve as steeds to several deities, and even have their own place in religion.

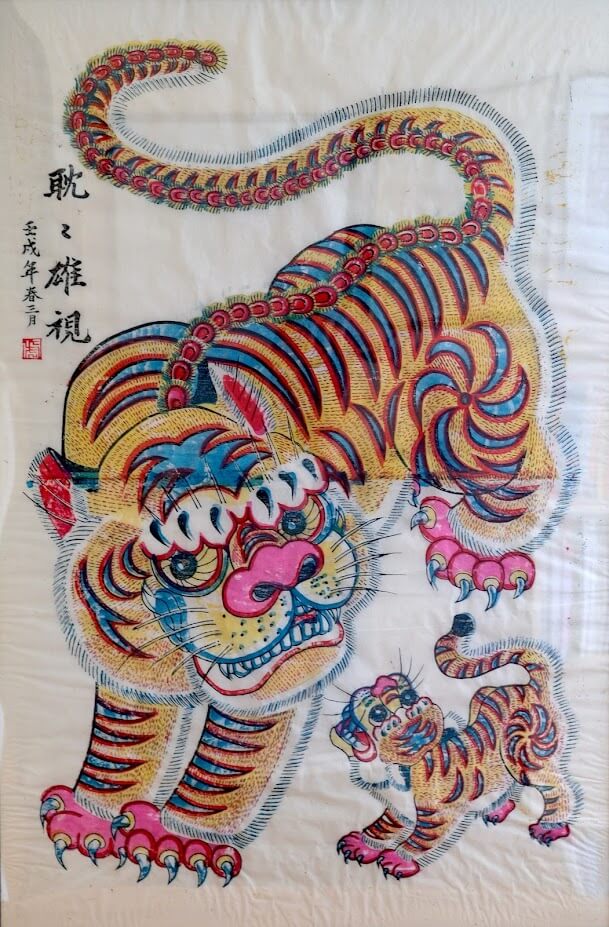

“Awesome Force of Nature”

Here’s an example of how the tiger can symbolise raw, irrepressible, elemental power. The title translates as “An Awesome Force of Nature” and depicts a snarling tiger resting deep in a mountain forest. In Chinese art tigers are typically depicted with stripes forming the character for “king” (王) on the forehead; like lions in the West, the Chinese see the tiger as king of the beasts. Pine trees, slow-growing and defying mountain snows and gales, are a stand-in for longevity, and the whole sense of the picture is of vigorous natural forces supporting a long and healthy life.

Although different woodblock-printing centres in China developed their own very distinct styles, not many signed their works. Here, however, the text at the bottom reads “By Yang Xiuyi of the Weifang New Year Picture Print Society”, a well-known workshop on eastern China’s Shandong peninsula operating into the early 1980s.

“Peace Throughout the Year”

Far more stylised is the next print from Wuqiang town in Hebei province, not so far from Beijing. Two tigers circle each other, surrounded by five red bats – a homonym for “five great blessings” – and flanked by lanterns illustrating the twelve animals of the Chinese zodiac. The main title reads “Peace Throughout the Year”, and the other two panels make up a phrase inviting wishes to come true and bringing good luck.

Like the previous print from Weifang this is a New Year Picture, put up during the Spring Festival to brighten the home, chase away misfortune and encourage prosperity for the coming twelve months. Despite the obvious zodiac theme, the central two tigers are here to repulse evil influences, not necessarily to represent their own tiger year.

Tiger and Cub

One common type of popular print features gate guardians, pasted up either side of the front door to prevent malevolent forces from entering the home. In some parts of China a pair of tiger prints like these protected against foxes: houses were built of wood, foxes were believed to trail fire from their red tails, so they served as talismans against the house burning down. Elsewhere, these prints might be displayed in a sick room or nursery to scare off illnesses.

This print is dated according to the sixty-year calendrical cycle, and was designed during a “renxu” year. This indicates the 59th year of the cycle, most recently in 1982, though that’s no guarantee that this print was actually made then. A printing block could remain in use until most of the details had worn away and it had begun to disintegrate; even then the design could be recut if there was a demand for it – some prints still in production originated during the Ming dynasty, over five hundred years ago.

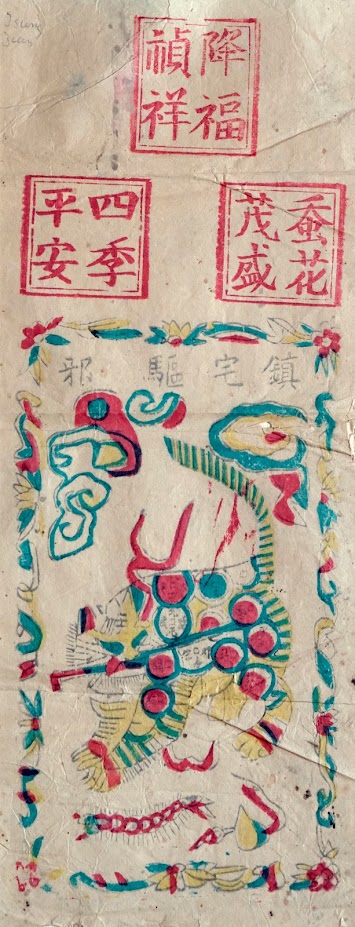

Zhang Daoling talisman

Here’s another protective talisman, this time of the Daoist patriarch Zhang Daoling. Zhang was a real person, and while I have no idea if he rode around on a tiger this image underlines the Daoist obsession in mastering (or working with) powerful natural forces.

Born around AD34, tradition says that Zhang lived in the mountains as a hermit, where he gained an ability to supress troublesome demons and founded the Heavenly Master sect of Daoism. According to one account, Zhang received the “Method of the Tiger Spirit” from a long-haired mystic named Liu Gen, and learned to refine pills of immortality – the goal of any Daoist alchemist.

In this print, made at Shanghai in 1927, Zhang is shown wearing a crown and wielding a demon-quelling sword while his tiger crushes the Five Poisons, represented by a toad, snake, centipede, lizard and spider. The small tiger at the back carries Zhang’s square seal, imprints of which are above in red, either side of a demon-repelling yin-yang-bagua symbol. Across the top, sets of three “ticks” represent the Daoist supreme trinity, while the characters 勅令mean “By Imperial Command”. The Chinese text reads “Seal of the Great Shangqing Palace, Dragon-Tiger Mountain, Jiangxi Province”. Until its destruction in 1930 – just three years after this print was made – Shangqing Palace was one of the major hubs of the Daoist religion, a position it held for a thousand years.

These talismans were in greatest demand for duanwu, the fifth of the fifth month, known today for its dragon-boat races but also considered the most unhealthy time of the year – stinking hot and humid across much of China – when the disease-causing Five Poisons were at their most noxious. It might again be pasted up in the home, or even pinned to clothing.

Money Tiger

A similar type of charm, this crudely-cut folk print from Shanghai shows the Money Tiger, body covered in coins, holding a sword in its mouth and subduing a centipede. Once more it’s a new year talisman to dispel bad luck and attract prosperity: the three red seal marks translate as “Bestow Blessings and Good Fortune”, “Peace Throughout the Year” and “Flourishing Silkworm Flowers” – a fairly common expression in the silk-producing heartlands of eastern China. The text in black above the tiger reads “Exorcism of Evil Spirits for a Town House”.

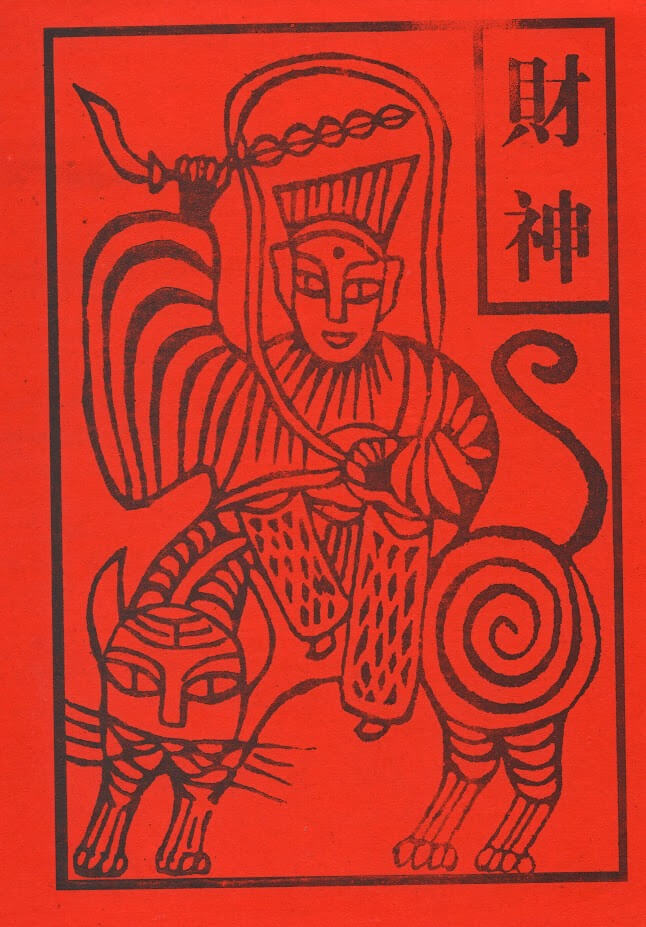

You can’t go far with popular prints without mentioning wealth deities, as attracting their blessings is one of the main concerns of Chinese folk religion. Aside from the Money Tiger above there are many, many wealth gods – including the generic Cai Shen, Liu Hai and his three-legged money toad, a Deity of Increasing Returns and even a God of Gamblers – but one of the best-known is Zhao Gongming.

Zhao Gongming

Zhao’s origins are described in the late-sixteenth-century popular novel Investiture of the Gods, a fantastical retelling of the overthrow of the corrupt Shang dynasty in 1046 BC by the up-and-coming state of Zhou. A valiant general from Mount Emei in Sichuan province, Zhao’s sense of loyalty made him fight for the crumbling Shang dynasty, until he was killed by the Zhou warrior-statesman Jiang Ziya. When the war was over, Jiang regretted Zhao’s death and had him deified as the military god of wealth. He represents commercial success, rather than sudden riches, so is worshipped by merchants and businessmen.

Zhao Gongming and Jiang Ziya as door gods

In this print from Zhuxian town in Henan province, Zhao Gongming appears on the left as a door guardian, paired with his rival Jiang Ziya. Zhao rides his trademark black tiger, which he subdued by writing a spell on its neck – again demonstrating Daoist power over immense natural forces. In one hand Zhao wields a ridged metal sword-breaker which, according to the novel, fired out exploding pearls; in the other hand (as befits a wealth god) he holds a slipper-shaped gold ingot. The Golden Dragon Scissors floating above are another of Zhao’s mystical weapons, able to chop even an Immortal in two. With such skills it’s not surprising that this deified tiger-riding warrior offers followers success in the cut-throat world of commerce.

Facing him, Jiang Ziya rides a yellow deer, which – along with his trigram-patterned robe and dried gourd – are all symbols of a Daoist magician.

Medicine Sage Wei

An esoteric religion which seeks to gain longevity – even immortality – by understanding and following the “natural way”, Daoism is often associated with magicians, alchemists and medics. This print from Beijing of the Medicine Sage Wei Cizang is of a type known as 紙馬, “Paper Horses”, small pictures of China’s myriad folk deities which were used to ask favours from benevolent spirits or protection from malicious ones. They were usually burned and the ashes sometimes consumed as medicine; “paper horse” is a splendid term for something designed to gallop off heavenward in a puff of smoke, carrying your prayer to the gods.

The print follows a standard format, with the central deity sitting behind an altar table, two attendants either side and a name board above. Sometimes the image is generic and the deity can only be identified by its name, but in this case specific iconography relates to Wei Cizang. The twisted rope-like object on the right side of the table are dried herbs (Wei was known for his prescriptions, rather than for using acupuncture or other healing methods). On the left side of the table is another dried gourd, the traditional pill-box carried by Daoist alchemists – the attendant front right also holds one.

Under the table are Wei Cizang’s two familiars. On the right but almost unrecognizable – the print was made from a worn, partially-disintegrated woodblock – is a dog which followed Wei on his house calls. It’s easier to pick out the tiger on the left, a creature often paired with Daoist physicians as a symbol of their “protective” medical skills.

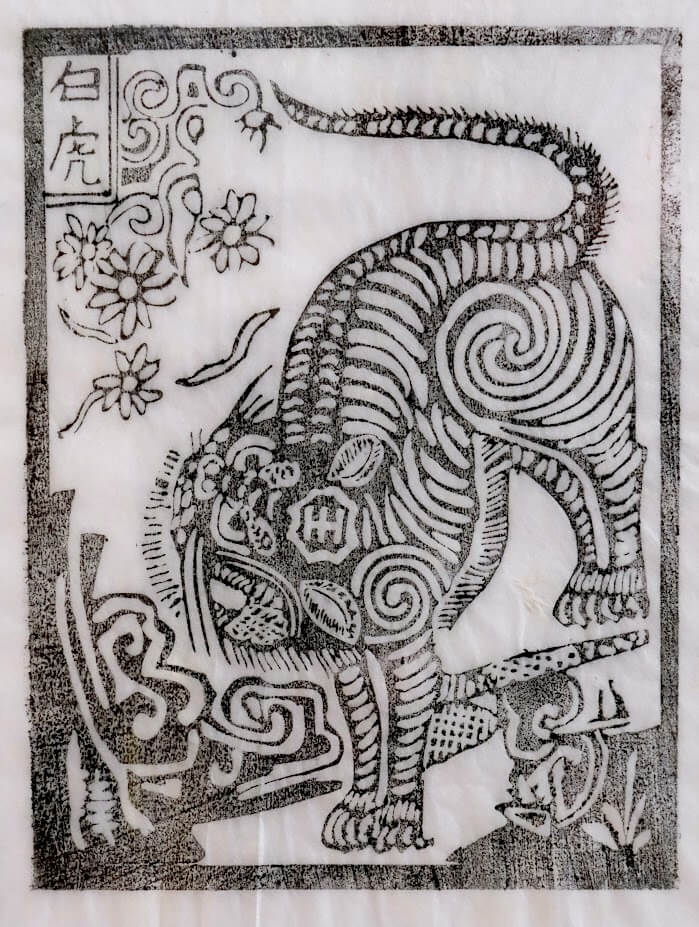

White Tiger of the West

The one place where the production and daily use of woodblock prints has survived on a scale approaching that of the nineteenth century is rural Yunnan province, way down in China’s far southwest. Partly this is just down to geography: the region is a very long way from mainstream eastern China and has managed to preserve many traditions which have faded out elsewhere.

This print is from Heshun village, near Yunnan’s border with Myanmar, and shows a White Tiger with bristling whiskers, the character 王 stamped firmly on its forehead. White tigers are not quite so benevolent as the usual version; they are more of an agricultural creature representing Autumn, pestilence and drought, and need to be appeased rather than sought out for protection. The tiger is believed to descend from the mountains in Spring, when its roaring wakes insect pests; during the jingzhe festival rural people bring gifts of meat to tiger shrines to keep it quiet and so protect their crops.

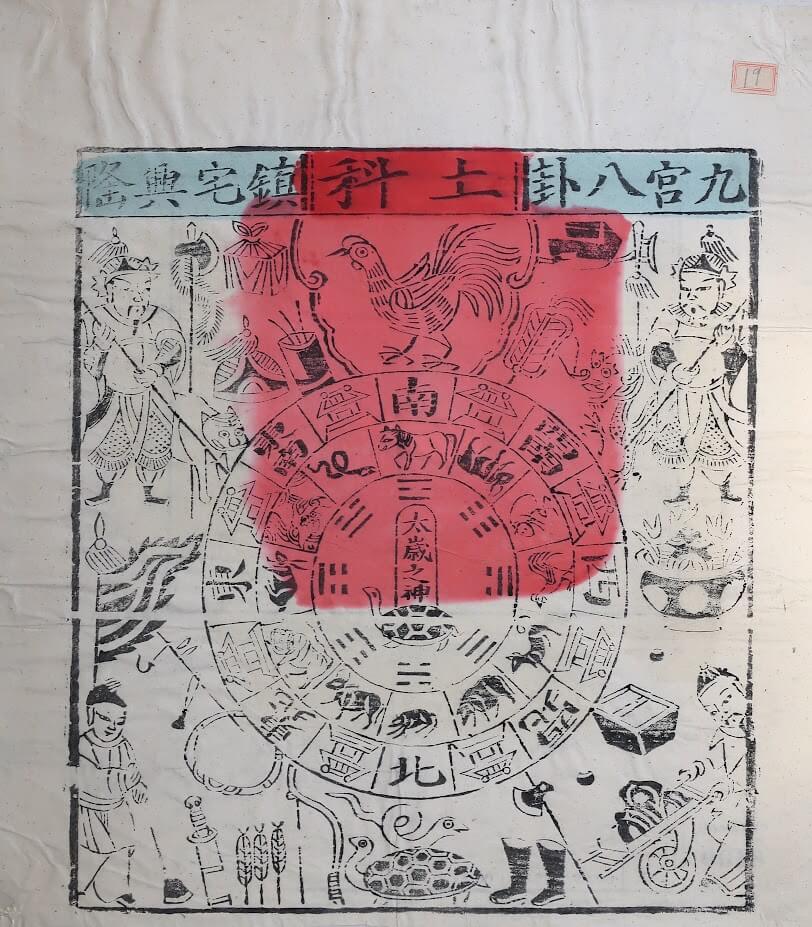

Earthly Departments

Yet even the White Tiger is an important component of the natural order by representing one of the cardinal directions, as shown on this geomantic (feng shui) wheel from Beijing titled the “Earthly Departments”. At the top is the Red Bird of the South, with the Black Turtle and Snake down at the bottom edge representing the north; top right side is the Green Dragon of the East, with the White Tiger of the West at upper left. Despite their reversal here, the phrase “Green Dragon to the left, White Tiger to the right” is shorthand for describing perfect geomantic conditions.

Other objects in the print relate to civil and military duties being carried out with due diligence, while the tablet-bearing turtle at the centre representing time and order is surrounded by rings linking the divination tools of compass points, zodiac animals and the eight trigrams. The overall purpose of this print is to protect a building project from causing disruption to local geomancy (or to protect against such disruption), by balancing out and counteracting any untoward forces.

David Leffman first visited China in 1985 and has spent over five years there in total, mostly working as a travel writer and photographer. He is also the author of Paper Horses: Traditional Woodblock Prints of Gods From Northern China, published in 2022.