Benjamin Guy Babington (1794-1866)

Monday 8th April marked the anniversary of the death of Benjamin Guy Babington, who died on that day in 1866. Babington was born on 5 March 1794 in Guy’s Hospital, London, where his father, William, was a physician, the hospital thus providing Benjamin Babington’s middle name; his first being after his father’s best friend, Benjamin Fayle. He was educated at Charterhouse from 1803-1807 and then went to sea as a midshipman. He left the navy in 1810 and attended Haileybury College before going to work in the East India Company service in Madras in 1812. In his first two years he learnt Tamil and probably some Sanskrit. In 1814 he visited his brother, Stephen, who was serving in the Bombay Civil Service, and from there he travelled overland back to England.

While in England he married Anna Mary, daughter of his father’s friend, Benjamin Fayle. The two went back to Madras in 1817 but due to Babington’s poor health they returned to England and Babington began to study medicine at Guy’s Hospital and Pembroke College, Cambridge, gaining his doctorate in 1831. He joined Guy’s Hospital but resigned in 1855 after a disagreement over policy. He was lecturer at the Royal College of Physicians, and president of several medical societies. He was also the inventor of several medical instruments and is particularly remembered for his invention of the laryngoscope.

So, why is the Royal Asiatic Society interested in remembering this esteemed doctor, Benjamin Guy Babington? Well, it seems that Babington, alongside his medical career, maintained his interest in India and Asia. He had been a fellow of the Madras Literary Society and became a Fellow of the Royal Asiatic Society in 1824. He served as its Secretary, in the early days of the Society, from 1826-1828 after the death of G.H. Noehden. Besides publishing medical texts he also published the pamphlet, “Remarks on the geology of the country between Tellicherry and Madras” and, in collaboration with Costantino Guiseppe Beschi, translated and published, “A grammar of the high dialect of the Tamil language, termed Shen-Tamil : to which is added, an introduction to Tamil poetry” and “Paramāṟatakuruviṉa katai: The adventures of the Gooroo Paramartan : a tale in the Tamul language : accompanied by a translation and vocabulary, together with an analysis of the first story”. We have copies of these within our Collections.

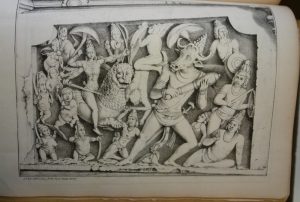

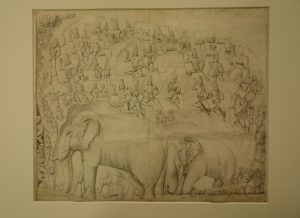

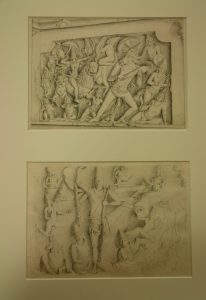

Babington also donated 11 drawings undertaken by Andrew Huddleston and himself. These were used to illustrate Babington’s paper, “An Account of the Sculptures and Inscriptions at Mahamalaipur” which appeared in the Transactions of the Society in 1830, after having been read at the Society in 1828.

The pictures were probably drawn when Babington and Huddleston visited the site for the first time, between 1812 and 1814. The style of the two artists is very similar and apart from one of the drawings, attributed to Huddleston, it is not possible to decide which man drew which picture. Most of the drawings have descriptions on the reverse in English, and some have Tamil descriptions.

We are grateful that Babington left this material with the Society so researchers can continue to benefit from his work.

On a completely different note, we look forward this evening to welcoming Dr. Rayna Denison from the University of East Anglia. She will be lecturing on “The Hidden History of Studio Ghibli: Short Films, Advertising and the Industrial Reality of Japanese Animation”. Studio Ghibli’s films have become famous around the world, but their animation production in other areas remains obscure. Ghibli, like most animation studios in Japan, supplements its feature film production by doing animation-for-hire. These ancillary productions take some unusual and varied forms. On the one hand, they have produced high profile advertisements for clients, and even animated music videos for Japanese bands, while on the other they have produced animation shorts, exclusively shown at the Studio Ghibli Art Museum in Mitaka, Tokyo. This lecture examines the different economic, aesthetic and corporate influences that can be traced across these shorts in order to think about how Studio Ghibli’s famous house style of animation is impacted by the industrial realities of Japanese animation production. We hope that many will join us this evening for such an interesting topic.

This will be the last blog to be sent out before the Easter weekend. Therefore, I wanted to take the opportunity of wishing everyone a happy Easter period and thank you for continuing to support the Society through reading this blog.