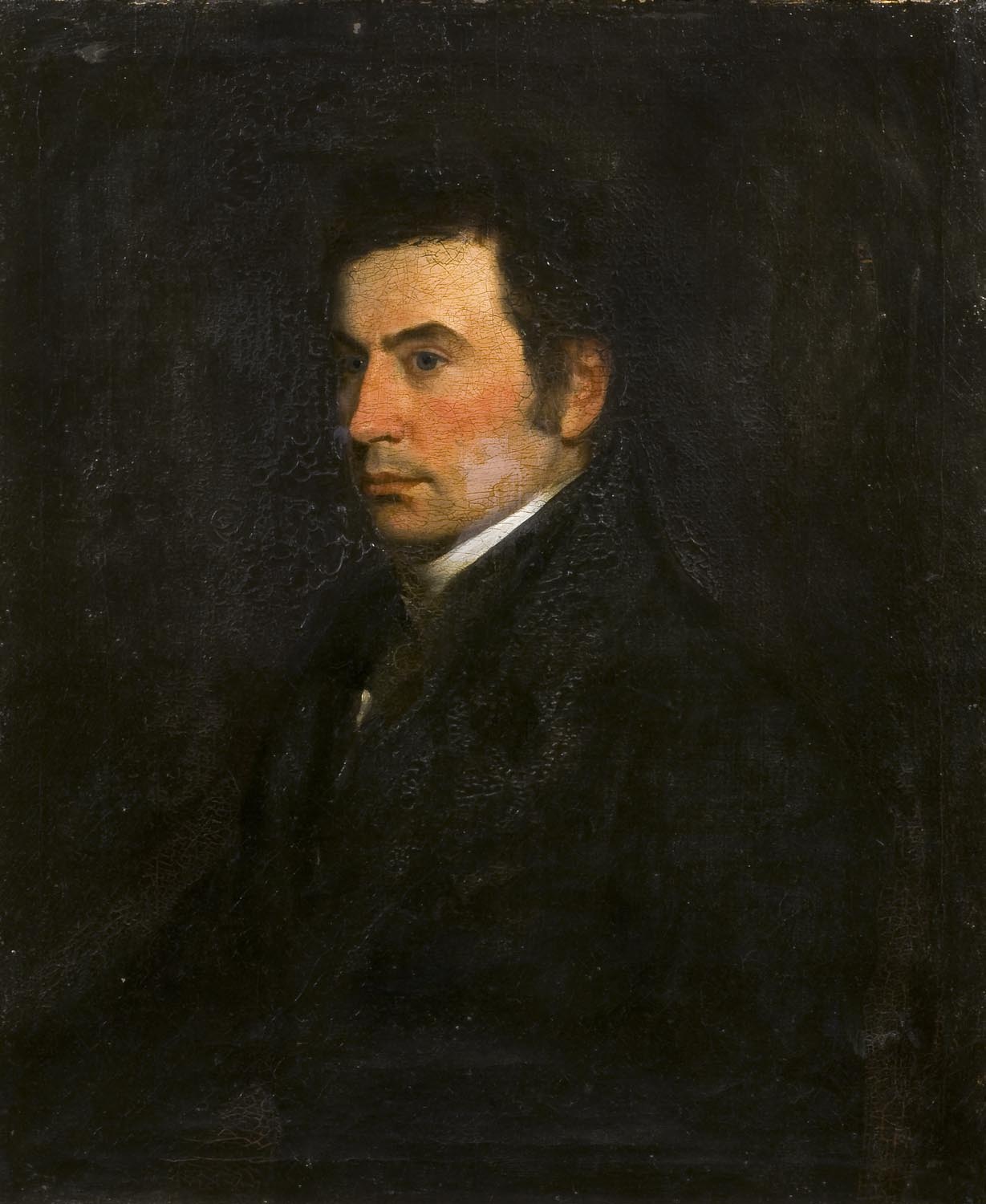

Thomas Manning (1772-1840)

In 2014, a cache of Thomas Manning’s papers were discovered. These were purchased by the Royal Asiatic Society, in 2015, with funding from The National Heritage Memorial Fund, Arts Council England / Victoria and Albert Museum Purchase Grant Fund, Friends of National Libraries, and several private donations. The papers, which include correspondence with his family and friends, notebooks, an early manuscript account of the journey to Lhasa, and official passports and documents, are now catalogued on to Archives Hub and they have the potential to provide a much more detailed view of his life than has previously been known. The archive was digitized with support from the Friends of the National Libraries, and can be viewed on the Society’s Digital Library here.

Thomas Manning was born in 1772, the second son of William Manning, rector of Diss. He was educated locally in Norfolk and went to Cambridge in 1790 to study mathematics at Gonville and Caius College. He was a very able mathematician but did not graduate because he rebelled against subscribing to the doctrines of the Church of England, which was necessary for matriculation at that time. However, he stayed on in Cambridge, preparing students for mathematical examinations and writing textbooks. Within the archives there are mathematical notes and manuscripts in English and French. For Manning mathematics was a lifelong passion: some of the mathematical archives date from the years shortly before he died.

Cambridge life also encouraged another of his passions – that of writing poetry and riddles. Amongst the many drafts of poems, riddles and explorations in language that are contained in the archives are a series of epigrams about the state of the toilets at Gonville and Caius – as you might guess, the poems are not complimentary!

But, at Cambridge, Manning developed another passion; the desire to learn about China and the Chinese. Manning hoped to discover: “a moral view of China; its manners; the actual degree of happiness the people enjoy; their sentiments and opinions, so far as they influence life; their literature; their history; the causes for their stability and vast population, their minor arts and contrivances; what there might be in China to serve as a model for imitation, ad what to serve as a beacon to avoid.”

![Letter from Thomas Manning’s father, Rev William Manning, expressing his concern regarding Manning’s proposed travel to China, [24 August 1803] (TM/1/1/27)](http://royalasiaticsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Manning-2.jpg)

Manning’s stay in France was forcibly extended by the outbreak of conflict between England and France. Englishmen, resident in France at the time, were not allowed to return home in case they would take up arms against the French. However Manning was well treated, being able to continue his studies in Paris or reside with the de Serrant family at their chateau in the Loire. After consistent appeals to Napoleon, explaining his desire to travel to China, Manning was allowed to return to England. He then studied for 6 months at Westminster Hospital to gain some medical knowledge that might be of benefit during his travels. He considered journeying overland to China via Russia but decided his Chinese language skills were insufficient. He therefore applied, via Sir Joseph Banks, to the East India Company to sail on one of their vessels to Canton.

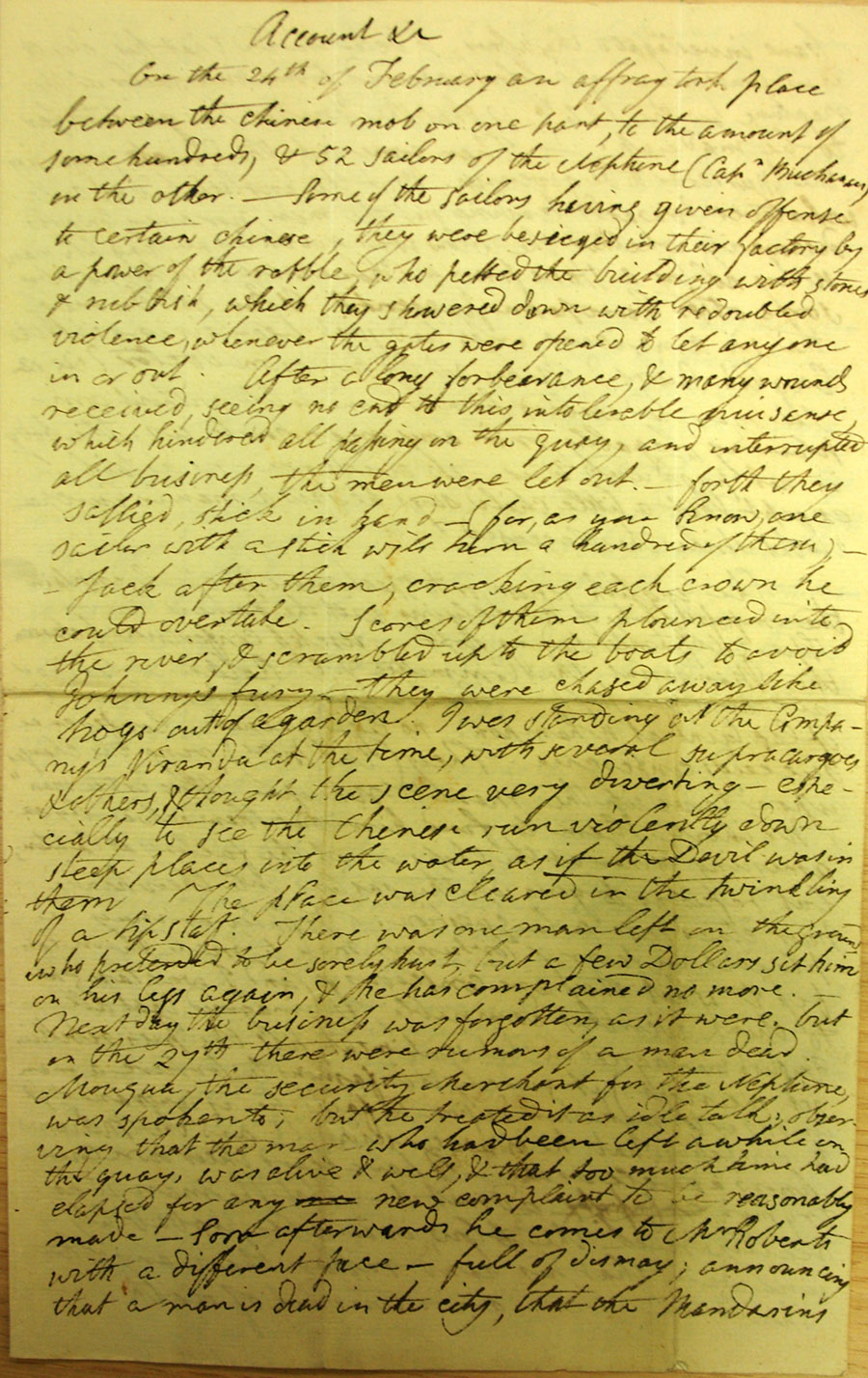

The Company agreed and Manning secured a berth aboard the Thames which sailed from Portsmouth in May 1806, reaching Canton in January 1807. Here he lived in the Company factory, set about learning the Chinese language, and undertook both medical and translation work. Manning included in his letters details of life and events in Canton. One such episode was the riot that led to the death of a Chinese man and precipitated the diplomatic incident over the crew of the East India boat, Neptune. Manning appears to have observed the events on the day and wrote an eyewitness account, as well as comments on the ensuing trial: “…The court is opened in a very striking manner – 1st Solemn & lofty words by a herald – then a lengthened resounding cry of hou… then a sonorous & aweful clangor of Gongs – But what is the examination that succeeded – in one word Nonsense! Each man asked to say that he is guilty or to accuse some of his companions. Each man refuses… To hear those ragamuffins speak they were all as gentle as Lambs that day… would not hurt a Chinaman for the world”.

Manning desperately wanted to get beyond the small area near Canton where all Englishmen were obliged to reside. In late 1807 he tried to offer his services as a physician and astronomer to the Emperor, but was not accepted. Then in early 1808 Manning tried to enter China through Vietnam. He later wrote of the project’s failure due to insufficient time and encountering a shipwreck which they rescued at his insistence. Despite these frustrations he continued to make progress with Chinese: “I have discovered the nature of the tones. I can speak. I can read. I am sure of being able to pursue the study of Chinese books in Europe.”

In 1810 Manning decided on the alternative plan to try to enter China via Tibet. He travelled to Bengal and arrived in Calcutta in early 1810. He wrote to his father of dealings with European “missionaries in Calcutta who claim to know something of the Chinese language but they have it wrong… their translations of Confucius are a map of mistakes”. There are eight letters from Joshua Marshman, the Serampore missionary, in the archive thanking Manning for his help with Chinese translation.

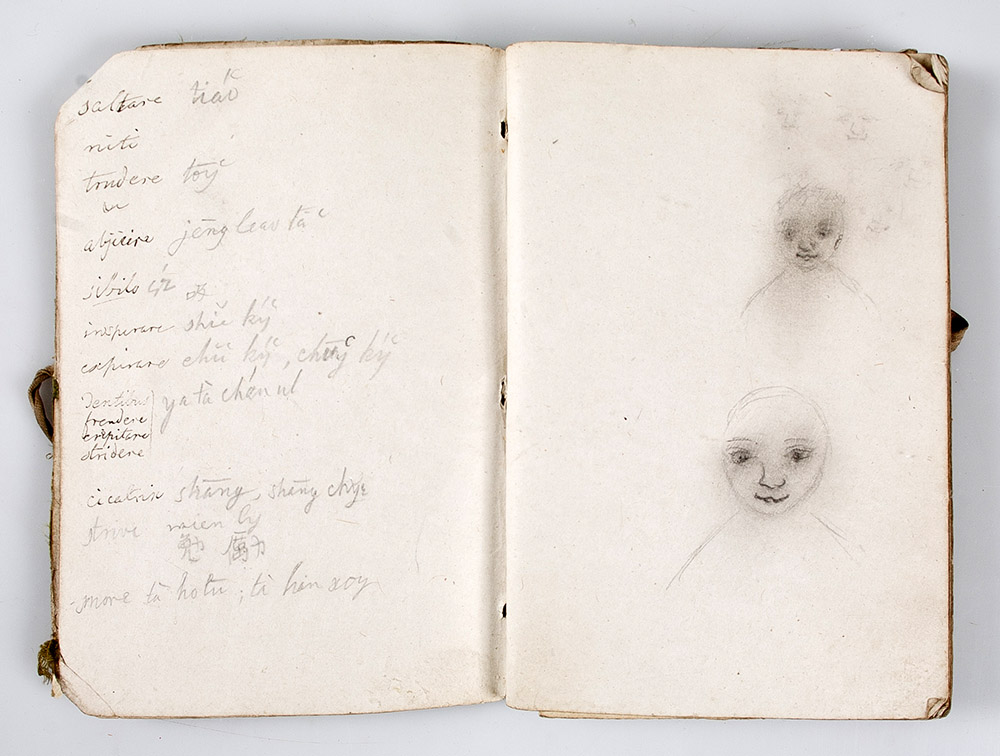

In Bengal Manning waited for permission to travel to China via Bhutan and Tibet. Permission came for the first stage of the journey, and Manning kept on going. In December 1811, he entered Lhasa, the holy city of Tibet, with his Chinese servant. On the 17th, after lodging in the town for a few days, Manning was allowed into the presence of the 9th Dalai, Lama – the six-year-old Lungtok Gyatso. Manning was deeply affected by this meeting. He drew sketches of the child and wrote:

“[He] had the simple and unaffected manners of a well-educated princely child. His face was, I thought, poetically affecting and beautiful. He was of a gay and cheerful disposition… I was extremely affected by this interview with the Lama. I could have wept with the strangeness of sensation.”

No other Englishman would enter Lhasa until the Younghusband expedition to Tibet at the beginning of the twentieth century. Many might think that Manning’s visit would mark a pinnacle in the career of an early nineteenth century English explorer, but for Thomas Manning reaching Lhasa, and not being able to proceed further, was a source of great disappointment. From Lhasa he was sent back the way he had come, unsuccessful in his bid to discover more about inland China. He returned to Canton to continue studying until another opportunity arose to see more of China with the mission of the Amherst Embassy which departed for Peking in 1816.

Manning was enrolled with the Embassy as an interpreter. Amherst objected to Manning’s beard and Chinese dress but George Staunton intervened to secure him a place. The presence of Manning, Staunton and Robert Morrison as the interpreters gives us a cameo of those interested in Chinese at that time – Staunton the East India man/diplomat, Morrison the missionary and Manning the independent scholar. The Embassy ended in failure partly due to disagreement over performing the “kowtow” ceremony and partly due to another perceived slight to the Emperor by Amherst. The Embassy remained in Peking for just a few hours before they were ordered to depart. Possibly this was the final straw for Manning – for he chose to return to England with the Embassy – a passage that involved shipwreck, and a stopover at St Helena to speak with the then exiled Napoleon. The archive contains notes from Manning’s conversations with Napoleon and Sir Hudson Lowe, Governor of St. Helena.

Back in England, Manning was still interested in China and Chinese. He had brought with him two Chinese men, one as a teacher and one as a servant. He had hoped that the East India Company would be pleased to employ these men to help prepare its employees for service in China, but he found them uninterested in either employment or in helping to defray the costs of bringing the men to England.

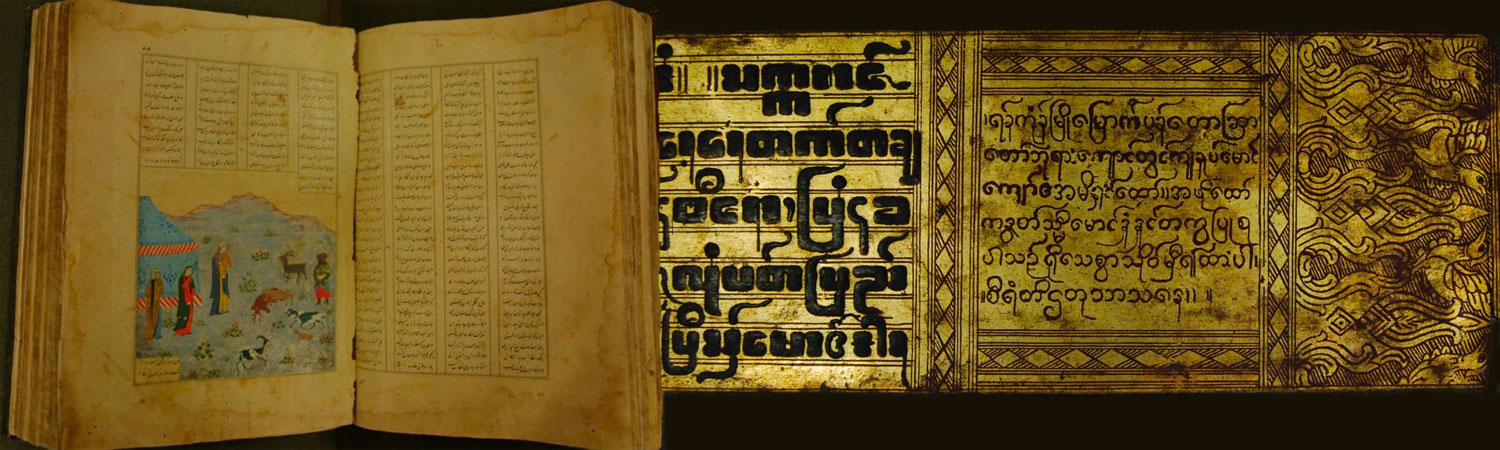

Manning continued his Chinese studies and revived old friendships with the likes of Lamb and George Leman Tuthill, an eminent physician. He became honorary Chinese librarian to the Royal Asiatic Society in 1824, and was active in helping Stanislas Julien, the French sinologist, find Chinese material. He was also still keen to learn new things and went to live in Italy between 1827 and 1829 in order to improve his spoken Italian. He settled in England near Dartford, Kent, where he had the finest Chinese library in Europe. This library was bequeathed to the Royal Asiatic Society and now is part of the Brotherton Library’s Chinese Collection (Leeds University)having been donated by the Society in 1963.

Manning did not publish any of his Chinese discoveries and therefore he has often been overlooked amongst those studying early Sinology and Orientalism. The Royal Asiatic Society are hoping that the acquisition and cataloguing of this archive, now available to researchers, might lead to a greater understanding of these topics, and of the life of Thomas Manning: not only the first Englishman to reach Lhasa, but also, possibly, the first independent English scholar of China and the Chinese, a gifted mathematician, a lover of riddles and a loyal friend.