Derek Davis on A S Pushkin’s A Journey to Arzrum during the Campaign of 1829 – Part 2

On Tuesday 25 October RAS launches Derek Davis’ English edition of A S Pushkin’s A Journey to Arzrum during the Campaign of 1829. Mr Davis continues his account of Society contacts with Russia then and now. As he explains, the Journal Supplement brings the Society’s earliest years, pivotal for Russia and British India, vividly to life.

In 1823, when the Royal Asiatic Society was founded, two European powers bulked large in Asia. British India had extended from its initial trading posts across most of the subcontinent. Russia had expanded across Siberia as far as Fort Ross in California, had crossed the Southern Steppes to the Black Sea and was advancing in the Caucasus.

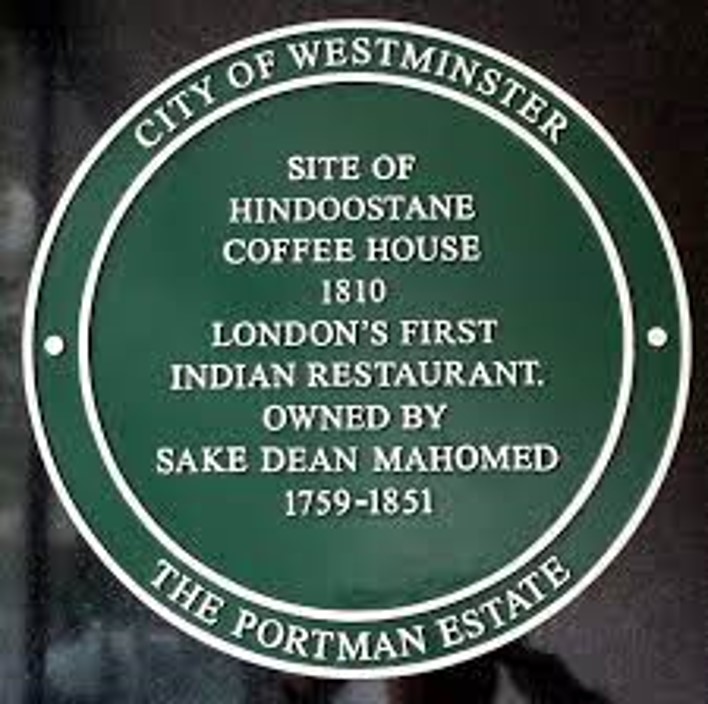

Europeans and Asians responded in classic fashion to the novelties of their more joined-up world. Europeans marvelled at strangely attired Asians and their exotic customs. Asians marvelled at oddly dressed Europeans with their new-fangled toys and machines. Both wanted to find out more. In Europe, “Orientalism” – fascination with the East – had long been all the rage. Europeans freely misconstrued, added value and were sometimes arrogant, but their enthusiasm was largely innocent of the malign agenda modern apologetics take as read. Goethe popularised the Persian ghazal (love poem) masters Sa’adi and Hafez. Asia, as imagined by Byron, the Irish poet Tom Moore and others, became a lively current in the Romantic Movement. Londoners could now order rice and curry at The Hindoostane Coffee House in George Street, first launched in 1810 by Sheikh Din Muhammad from Bihar, and at other restaurants.

They could also now enjoy hookahs with “chilm (clay bowl) tobacco” at the Coffee House. The Daniells’ Oriental Scenery of Hindoostan (1816) circulated spectacular, hitherto unseen, views from India to China, all captured on camera obscura and reproduced in aquatint, the latest technique just short of chemical photography. The Society’s Royal Patron George IV had recently completed his Brighton Pavilion. Georgian Indomania proceeded in linear descent from Herodotus, Europe’s not-quite-European first historian, who had tabulated his smaller Anatolian world, recording the “wondrous achievements” (thaumasta erga) of the Greeks and Persians and tracing how they came to fight. His “Histories” were a presentation (apodeixis) of his research (historiē).

The Society’s remit was to investigate all aspects of Asia and encourage science, literature and the arts in relation to Asia. Like minds across Europe were all engaged in the enterprise. Geologists searched out new deposits. Linguists searched on for the ancestral home of Sanskrit, Greek and Latin. Zoologists and botanists catalogued fauna and flora, using latest taxonomy techniques developed by Linnaeus in his work on Scandinavia. Orderliness did not entirely cope with the challenge of the new but somehow lessened it. The Society’s Oriental Translation Fund made Asian classics available in English. Several early titles covered West Asia and Russia. The Fund commissioned a translation of Sayyid Mohammed Reza’s Seven Planets, a Turkish history of the Crimean Khans, from Mirza Alexander Kazembek at Kazan University, who would go on to become Russia’s pre-eminent oriental scholar. He sent them his critical edition of the original but did not in the event translate. Other early Russian members included German academics working in Russia and the artist Sir Robert Ker Porter, resident in Petersburg. One Russian enthusiast, the mining engineer G I Spasski, even circulated the Society’s first Articles of Association in Russian, in his Petersburg journal Aziatski Vestnik.

Pushkin’s Journey to Arzrum revisits the 1820s in the spirit of the Translation Fund’s early endeavours. This was a turbulent and defining decade in Russian politics. Longstanding momentum for Russian constitutional reform collapsed with the failure of the 1825 Decembrist Revolt. Easily suppressed, it left the country’s politics enduringly polarised. The decade closed with impressive Russian victories over Persia and Turkey, establishing an interlude of Russian dominance in the Middle East. London now contended with Petersburg at the Ottoman court. British India, originally drawn into Persia to counter Napoleon’s designs, found itself face to face not with France but Russia. The Crimean War and sustained Anglo-Russian rivalry across Central Asia, shorthanded as the “great game” of the Survey of India’s and Kipling’s exploring “pundits”, followed.

Russia’s 1828-9 successes were intimately bound up in the 1825 Revolt aftermath. Decembrists exiled to the Caucasus and regime stalwarts in the army somehow struck a wartime patriotic truce and – going well beyond that – found a joint chemistry that delivered exceptional results. This winning formula was quickly set aside once victory had removed the external threat. Pushkin – present through a chapter of accidents at the capture of Erzurum – wrote it all up in the Journey. Severe constraints necessitated text that reads innocuously to the casual eye. Many have scratched their heads at the apparent lack of comment on such momentous events. Pushkin in fact offers pervasive commentary but it lurks implicitly or is ingeniously tucked away. His exercise of this art contributed to technique for handling what could not openly be said that became regular in Russian and underground literature. The Journey’s finale is, as one might expect, skilfully crafted. Pushkin and Mikhail Pushchin – arguably the single most important player in the fighting – stage a spoof review-reading, and laugh uproariously at the lesser talents about to claim their place in the sun. The laughter is not confined to litterateurs. It embraces officials, soldiers and all conformists destined to prosper under Tsar Nicholas I’s absolutist regime. Nicholas’ new non-inclusive Russia inevitably failed to sustain the exemplary performance glitteringly showcased by a transient combination of political opponents.

Pushkin has plenty more to tell us, not least about Orientalism. He quickly sends up European flights of fancy about Asians in encounters with a Kalmyk girl and the Persian court poet Fazil Khan (Chapter 1). His poem To a Kalmyk Girl is a masterly debunking of the genre. Fazil Khan instantly collapses grandiloquent “oriental” salutation, demonstrating that what educated Europeans and Asians really have in common is ordinary shared human civility. Pushkin now favours setting one’s own stamp, like Byron, on oriental models. Tom Moore, criticised for “slavishness”, is prayed in aid at the Tbilisi baths (Chapter 2) to illustrate the genre’s fixation with the erotic, already subverted by Georgian ladies of all shapes and sizes casually disrobing at the bathhouse, and to poke fun at Tsar Nicholas and his Empress who had starred in a 1821 Berlin extravaganza based on Moore’s Lalla Rookh.

Pushkin’s poem From Hafiz is another gem, celebrating the ghazal and gently ribbing its favoured pederastic motif. Eroticism recurs in Chapter 5, above all to disguise a call for Russian political reconciliation. But it also serves to make fun of Captain Abramowicz, who turned the Russian commander Paskevich against Pushkin’s Decembrist friends. Their visit to Osman Pasha’s harem (“the makings of an oriental novel”) already itches for the come-uppance that surely awaits him. It would be delivered years later, after Pushkin’s death, in Warsaw where Abramowicz had become Paskevich’s police chief, by the unscrupulously self-promoting vaudeville artiste Lola Montes.

The Journey also broaches the murky fate of A S Griboyedov, Russia’s ambassador to Persia, who was murdered with almost all his staff in 1829, prompting international sensation. He had negotiated the treaty consolidating major Russian territorial gains and a large war indemnity, bargaining in the thoroughgoing style of the military campaign itself, to considerable Persian discomfiture. The Supplement revisits the evidence surrounding his murder, which points to Persian culpability and a co-ordinated government cover-up. It also makes available in English the single Russian survivor’s account. A British PR initiative designed to bolster the Persian government storyline, a detailed picaresque account compiled by George Willock and published in Blackwood’s Magazine, is shown to have succeeded only too well in pre-empting the record and confusing later researchers. Accusations of British complicity in the massacre trace back to Paskevich’s ongoing wrangle with the Foreign Minister Nesselrode, a notorious Anglophile, over control of treaty negotiation. Persians picked up on the idea in their dealings with Petersburg and a Russian game of “hunt the British agent” has, engagingly, continued ever since. Pushkin places Griboyedov at the forefront of Decembrist achievement in the Caucasus, contriving an encounter with his coffin on the road and adding his own eulogy (Chapter 2). Beautifully drawn, it resembles the very best obituaries, celebrating Decembrist characteristics almost with a touch of Pericles on the greatness of Athens.

Firuza Melville and I renewed these Society contacts with Russia, presenting papers at the 225th Griboyedov Jubilee Conference held at Khmelita, near Smolensk, in January 2020. People there gave me valuable comment on my work, which I outlined, and were keen to see the full English edition published.

Derek Davis