The Personal Papers of Henry Thomas Colebrooke

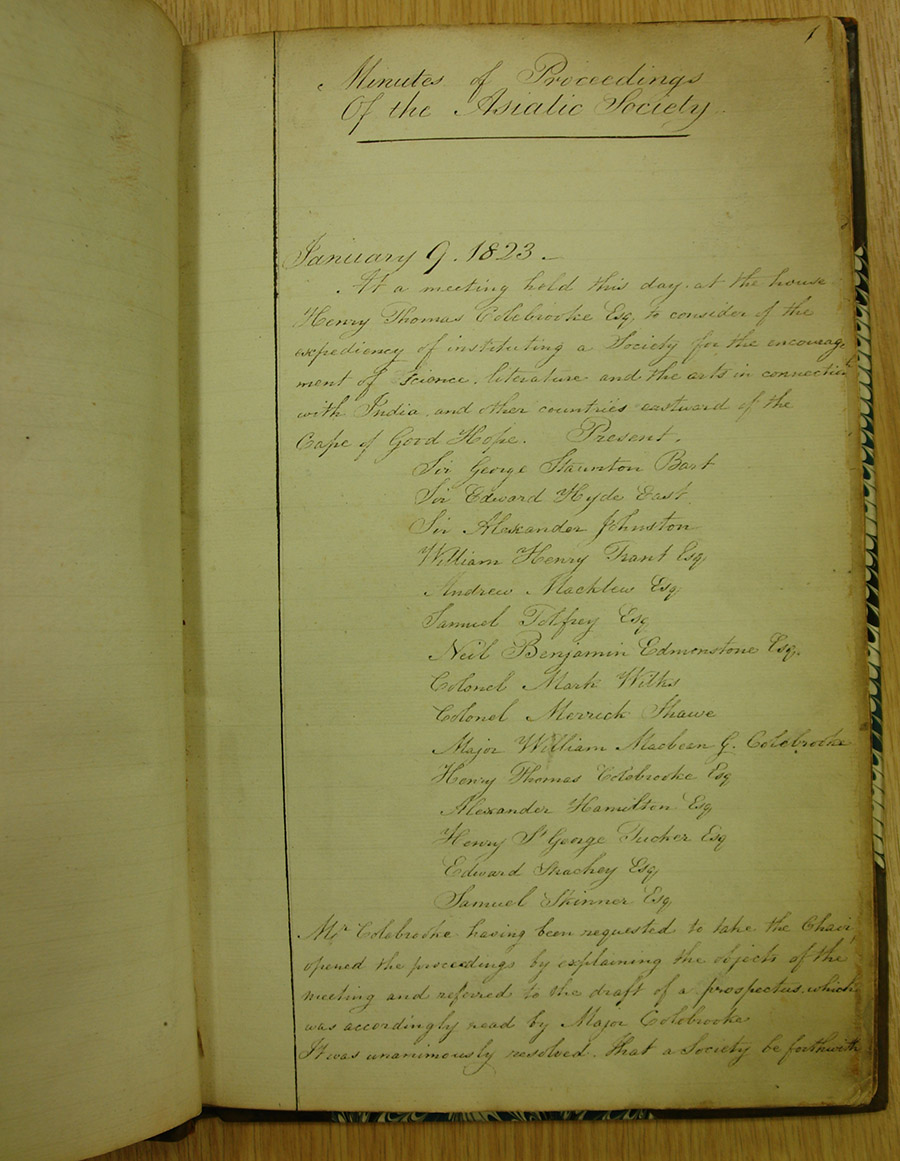

Henry Thomas Colebrooke (1765-1837) was the founder of the Royal Asiatic Society; the preliminary planning meetings were held in his house “to consider the expediency of instituting a Society for the encouragement of science, literature and the arts in connection with India, and other countries eastward of the Cape of Good Hope”.

He had already been President of the Asiatic Society of Calcutta from 1806-1815, so was well-positioned to instigate the formation of such a Society. On 15 March, 1823, a meeting was held at the Thatched House Tavern, St. James’ Street, London for the founding of the Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. Royal was added to its title later that year after King George IV granted its charter.

But the Society’s founding was only one of Colebrooke’s many achievements and interests, and one that came fairly late in his life. Colebrooke was tutored at home, and by the age of 15 was proficient in classics and mathematics. However, his family were not sufficiently wealthy for him to live the life of a monied gentleman. It was necessary for him to become employed. In 1782, Colebrooke sailed to India to take up a writership post with the East India Company. Thus began his rise through the ranks of the Company and from administrative to legal and academic roles. He became a scholar of Sanskrit and was appointed to complete the Digest of Hindu Law, which had been left unfinished by the untimely death of Sir William Jones. He translated other Sanskrit material and created a Sanskrit grammar whilst rising in role to become judge of the civil and criminal courts, professor at Fort William College and President of the Asiatic Society.

He retired from service in India in 1814 and returned to England. But he had certainly not retired! Colebrooke stayed very active in promotion of knowledge. He was a member of the Royal Society of Edinburgh and the Geological Society of London, quickly becoming one of its vice-presidents. He was also elected a member of the Linnean Society, the Royal Society, the Royal Institution, the Medico-Botanical Society and was a founding member of both the Astronomical Society and the Zoological Society. And then, of course, the Royal Asiatic Society. He also owned land in South Africa with which he hoped to undertake successful plantation farming.

I have recently spent time listing and preparing the Personal Papers of Henry Thomas Colebrooke which are part of the RAS Collections. The catalogue is now available online with Archives Hub. It is a small collection consisting of two series but both of these provide fascinating, though very different, insights into the character of Henry Thomas Colebrooke and into early 19th century life. The first is a Memoir and Autograph book, donated to the Society in 2009, which contains biographies and obituaries for both Colebrooke and Horace Hayman Wilson, first Professor of Sanskrit at Oxford University.

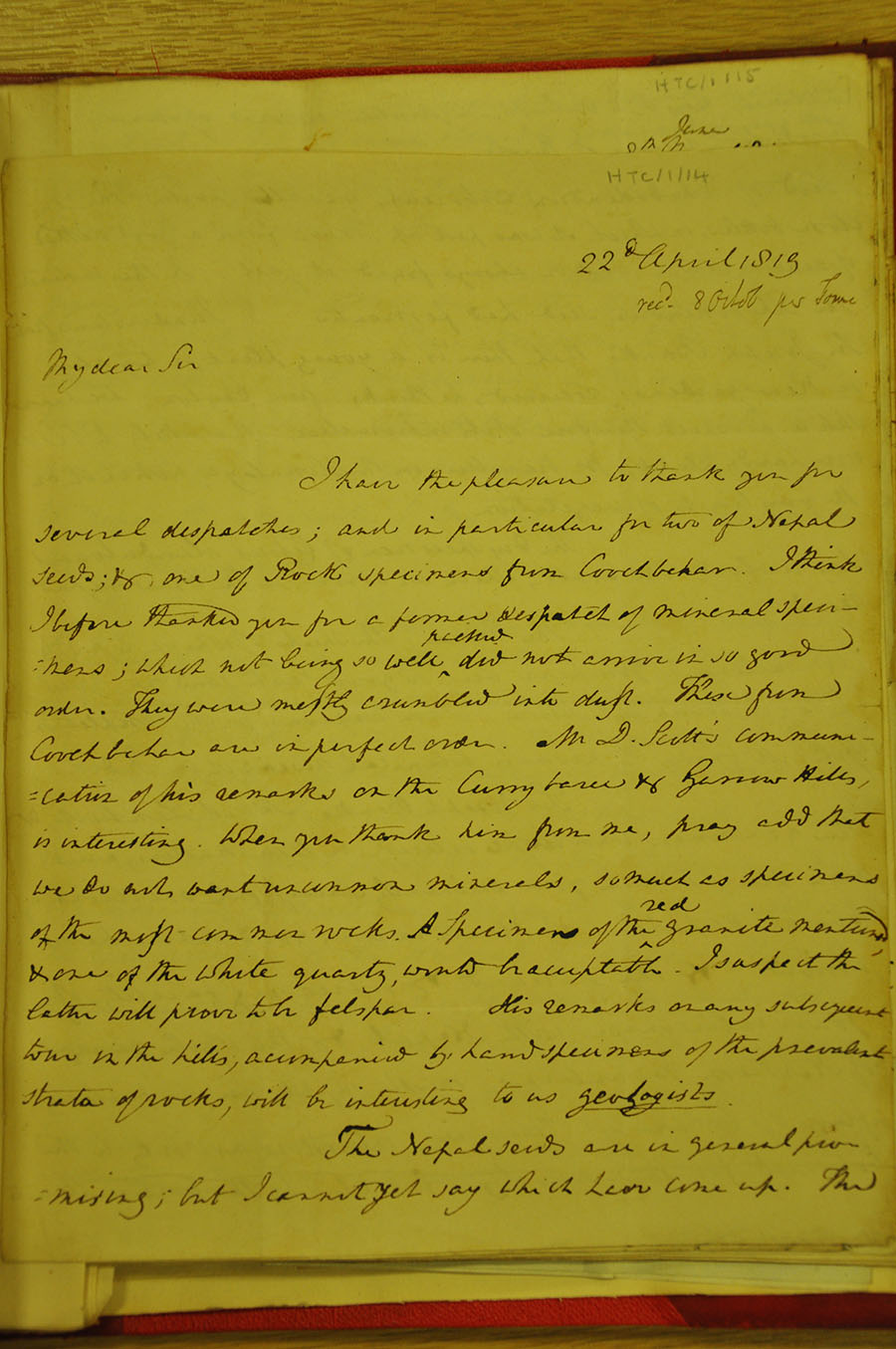

It is unknown who created the Memoir and Autograph Book. On the inside of the front cover there is a bookplate for Frederick Hendricks, dated 1893, who was an ancestor of the donor, but also a sales notice for the book. This suggests that Hendricks bought rather than created the book. A clue to the compiler might rest with a series of letters that are within the book, though this can only be supposition. The Autograph book contains 30 letters from Colebrooke to Nathaniel Wallich. These concern Wallich’s appointment as Superintendent of the Botanic Garden in Calcutta (Kolkata). Once appointed Wallich is active in sending specimens to England – both seeds and live plants. Colebrooke advises how to package, when to send and to whom they should be sent. The advice changes – first to send to individuals; then to the East India Company and other Institutions when the tax was too great; and then back to individuals when they began to claim they were not getting their share! No doubt Wallich took heed of the advice but considering that each letter took approximately 5-6 months to reach India (Wallich has appended the date of receipt to most of the letters), it must have been difficult for him to be sure what exactly Colebrooke wanted of him.

Colebrooke also asked Wallich to send geological specimens and to be involved in sending plant species to South Africa, to trial which would thrive in the climate around the Cape of Good Hope. In 1822, Colebrooke also took charge of sending books and periodicals to supply the Library at the Botanic Garden after the East India Company agreed to give £200 a year for the next 10 years to provide material for the library. Colebrooke actively encouraged Wallich and other scientists in India to join the Geological and Linnean Societies and, later, the Royal Asiatic Society and would use research material that they sent to present papers at the Societies’ meetings.

The second series within the Personal Papers consists of correspondence between Henry Thomas Colebrooke and his niece, Belinda Sutherland Colebrooke. These are photocopies of the original letters but, again, give interesting detail about Colebrooke’s life and the social and political milieu in which he mixed. Belinda was one of two daughters of Henry’s brother, George. After George’s death, Belinda’s mother took them to Scotland where she became involved with a series of affairs. Belinda, and her sister Harriet, were eventually made wards-of-court and placed with a foster mother, Mrs Lee. This series of 40 letters date from 1816, when Belinda was 16 years old, until 1824. Unfortunately Belinda died in 1825 but not before she had married Charles Joshua Smith, 2nd Baronet, in 1823. Henry obviously took a keen interest in the girls’ lives and encouraged Belinda in her studies, suggesting books for her to read and a suitable language tutor. The letters reveal some of the complexities of the time concerning fostering and also the holding of political seats; alongside living in Scotland, Brighton, Worthing (not satisfactory!) and London.

It has been really fascinating delving into these Papers and it is hoped that the online Catalogue will encourage new researchers to access this material.