Sir Stamford Raffles: Exhibitions, Collections, Legacy

This post is by Edward Weech. Nancy Charley, who writes most of our blog posts, is on holiday.

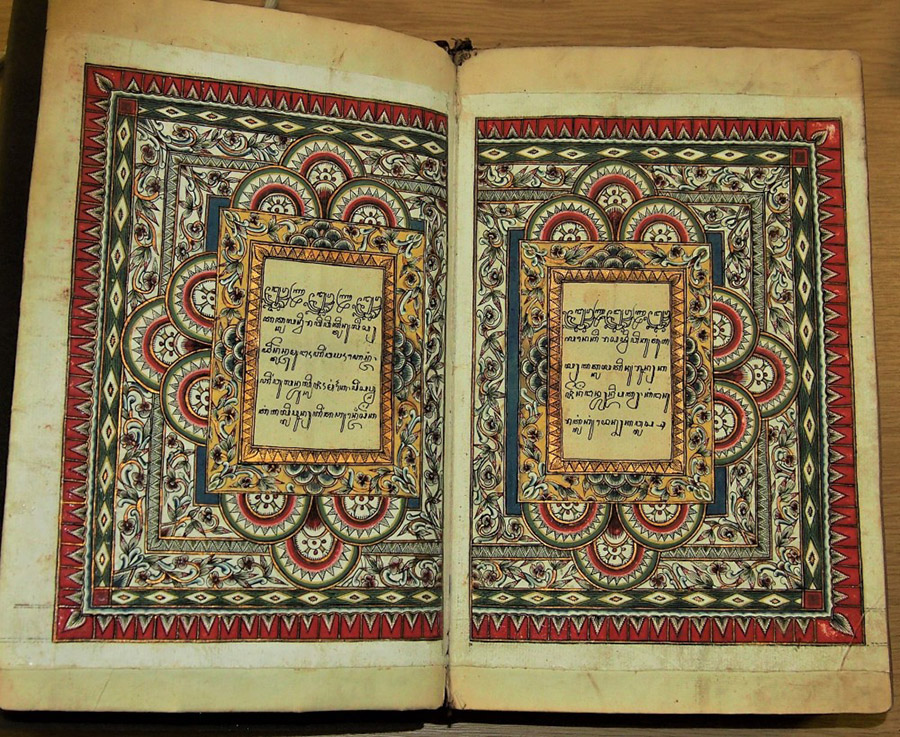

Last week, I was fortunate to be able to attend the opening of the British Museum exhibition, “Sir Stamford Raffles: collecting in Southeast Asia, 1811-1824”. This new exhibition highlights a number of objects from Java and Sumatra collected by Sir Stamford Raffles (1781-1826), who is chiefly known today as the founder of the state of Singapore. We are delighted that one of our manuscripts (RAS Raffles Java 7) is featured in the exhibition. The manuscript features beautifully decorated initial pages, and is one of 124 Malay and Javanese manuscripts donated to the Royal Asiatic Society in 1830 by his second wife, Sophia, Lady Raffles (1786-1858). The Raffles family donated most of his collection to the British Museum in 1859 and 1939.

In the employ of the East India Company from the age of fourteen, Raffles had a relatively humble education, but his great intellectual curiosity brought him into the company of well-known scholars including Dr John Leyden (1775-1811) and William Marsden (1754-1836). Raffles worked his way up through the ranks of the Company and eventually came to be entrusted with the Company’s political strategy in South-East Asia. There, he orchestrated the conquest of Dutch-controlled territories after Holland was annexed by France during the Napoleonic wars.

Raffles was subsequently appointed Governor of the Dutch East Indies, and in this capacity he travelled widely, collecting information about the languages, history, and products of Java. What he learned and collected helped to inform his History of Java, which was published in 1817. Much of Raffles’ collection was lost in a shipwreck in 1824, but the British Museum exhibition highlights the kinds of objects that he collected. While in Java, Raffles’s first wife, Olivia Mariamne Devenish (1771-1814), died suddenly; she was buried next to his friend John Leyden, who had died of malaria a few years earlier. All but one of Raffles’ young children died in Sumatra.

A proponent of free trade, Raffles opposed the monopolist policies that had been imposed under Dutch rule, and sought to implement reforms – including against the practice of slavery – which, he believed, would improve the conditions of life for people in Java. (After his early death from a brain tumour, Raffles’ grave in Hendon remained unmarked, allegedly due to the hostility of a vicar who objected to Raffles anti-slavery campaigns.) Raffles’ belief in free trade is perhaps best reflected in the history of Singapore, which he did much to shape. At the same time, Raffles was a strong believer in the British Empire, and he was not averse to using military force to defend its interests. One of the most controversial acts carried out by Raffles in Java was the invasion of Yogyakarta, in 1812, during which the kraton (palace) was badly damaged and looted.

The exhibition helped me reflect on how we think about history, and the role that heritage institutions play in helping people understand the past and live together in the present. How do we respond to the fact that the moral standards by which we judge international relations today are so different from those that prevailed – not just in Great Britain, but everywhere else – in the early nineteenth century? People in the past encountered new cultures in ways that were shaped by history, not in the ways that we (or they) might have chosen. It is important to point out where our forebears committed mistakes or crimes, but it is equally important to do justice to them when they tried to do good by the light of their own times. The extent to which conquering powers across history sought to understand, appreciate, and promote the merits of other cultures, has varied widely – and indeed, has varied even within the course of individual empires. I think the best conclusion is that we should aspire to remember our predecessors in a spirit of sympathy, rather than one of repudiation. After all, we might have reason to hope that future generations will be forgiving about our sins, too.

This free exhibition is open until 12 January 2020, and I encourage our readers to go and see the wonderful objects that attest to the rich cultural history of Java and Sumatra.

The Society’s lecture series resumes this week, with a lecture at 6.30pm on Thursday 26 September, when Dr Stefan Halikowski-Smith (Swansea University) will speak on “Two Missionary Accounts of Southeast Asia in the Late Seventeenth Century”. His lecture will address two previously unpublished missionary accounts from post-1688 Thailand. We hope you will be able to join us then.

Finally, we apologize if anyone has had difficulty contacting us over the Summer. For much of August and early September, the Society’s internet connection was seriously disrupted due to an external network fault with our supplier, Virgin Media. We are hopeful that the issue has now been resolved and that our communications can return to normal.