From the archive: The Seven Planets by Sayyid Mohammed Riza

Our Librarian Ed Weech recently made a striking discovery in the Society’s archive, topical today and thoroughly evocative of the world in which the Society came into being.

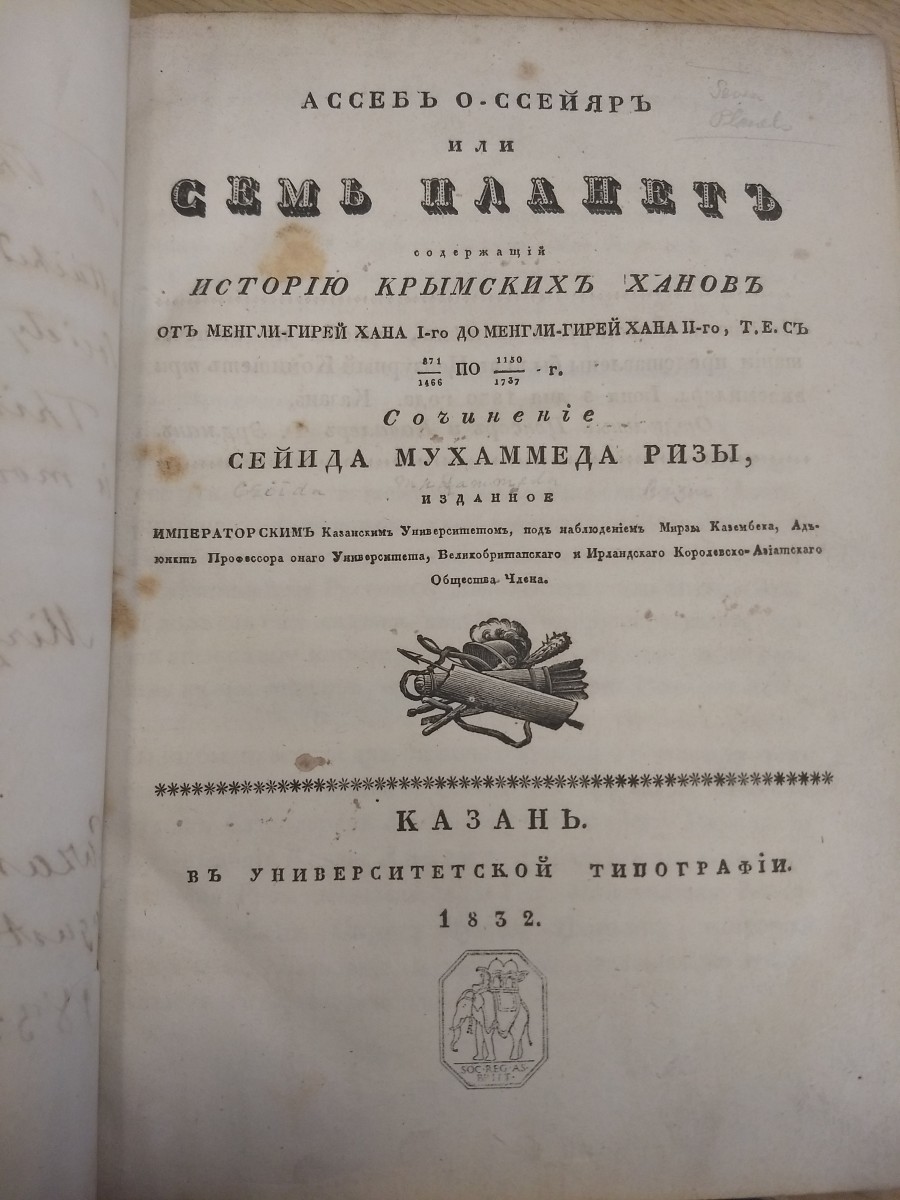

The Seven Planets (sab’a sayyara) by Sayyid Mohammed Riza is a history of the Crimean Khans in Ottoman Turkish, published by Kazan University in 1832. Riza completed this in 1737. In 1824 the university acquired a 1755 manuscript from the Kazan Mulla who had obtained it from a Bukharan returning via Kazan from pilgrimage to Mecca. The edition was prepared by Alexander Kazembek (1802-1870) who would go on to become the pivotal figure in Russian oriental studies, much like William Jones or Henry Colebrooke in British India. The text, collated since with other surviving manuscripts, republished and due to be fully translated, has become an established mine of information on Crimean history.

This book sheds light on the circulation of knowledge at a time when scholars and enthusiasts in all the main European centres were busily tabulating information of every kind about then little-known parts of Asia. Kazembek was an Azeri from Rasht. Converted to Presbyterianism rather than Orthodoxy by Scottish missionaries at Astrakhan, he was – Firuza Melville points out – left suspect in the eyes of Russian authorities who posted him to Omsk but were persuaded by Karl Fuchs, the Rector of Kazan University, when Kazembek passed through the city to allow him to join their teaching staff.

By 1830 he had become Associate Professor of Arabic and Persian and in 1846 succeeded Franz Erdmann as Professor. Erdmann, himself an early RAS member, may have encouraged Kazembek to join. RAS features prominently on the Seven Planets title page: “published…under the supervision of Mirza Kazembek, Associate Professor of the University, Member of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland.”

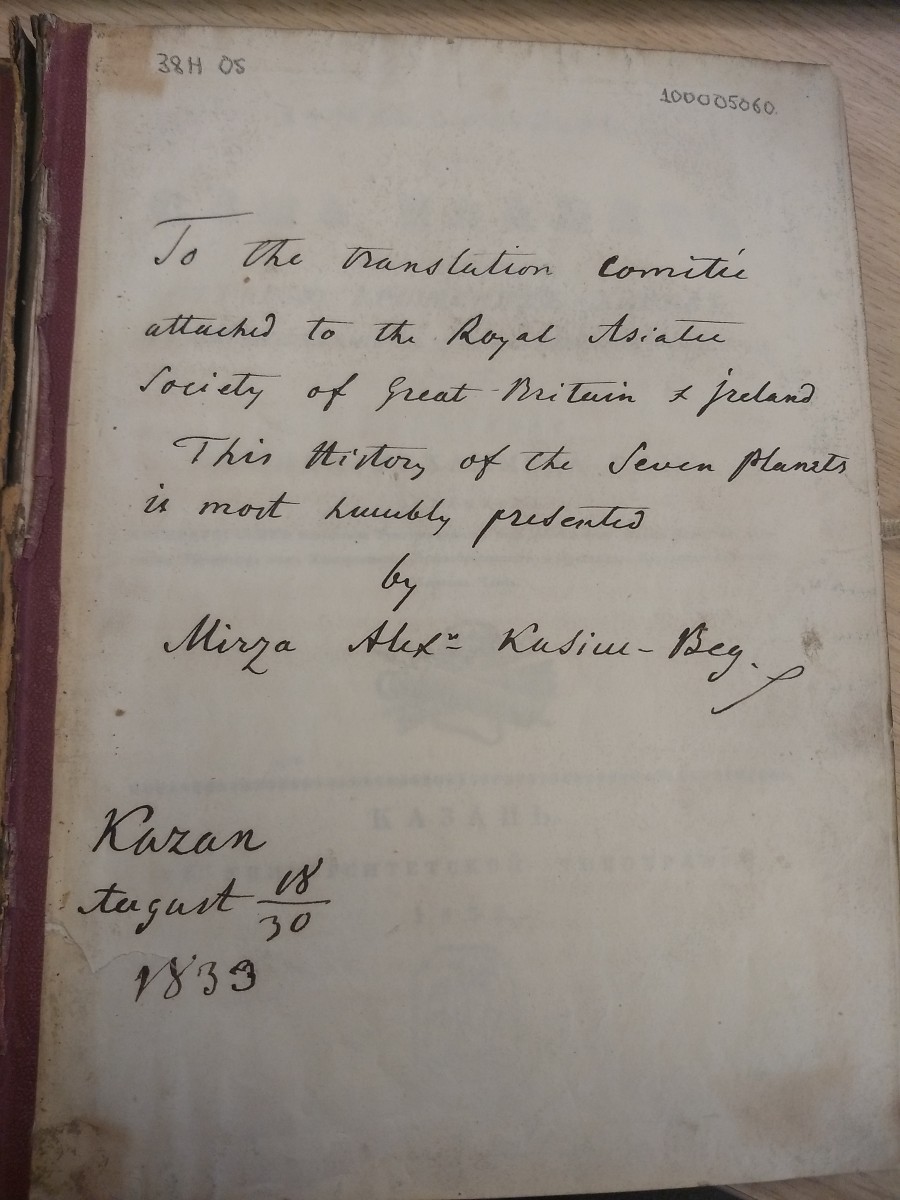

Kazembek says in his Introduction that colleagues had pressed him not just to edit Riza’s text but translate it, adding “the London Asiatic Society proposed the same.” He had rejected this, on the basis that Riza’s Turkish was highly ornate and a summary version presenting mainly factual content would be of greater practical value. Earlier exchanges explain his very precise English flyleaf inscription: “To the Translation Commit[t]ee attached to the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland/ This History of the Seven Planets is most humbly presented…”

The Seven Planets are, allegorically, the most celebrated of the 33 Crimean Khans Kazembek lists. He identifies them as Mengli Giray Khan, Sahib Giray Khan, Devlet Giray Khan, Ghazi Giray Khan, Bahadır Giray Khan, Hajji Selim Giray Khan and Mengli Giray Khan II. Riza probably drew his title from The Seven Planets of Alisher Nava’i of Herat, the prominent 15th century Turki author, who was in turn referencing Jami’s Haft Awrang (Seven Thrones). This all reaches back to Bahram V who features in the Shahnameh and takes centre stage in Nizami’s Seven Icons (haft peykar). Bahram’s brides come from across the globe, the Seven Climes of Greek geography echoing a Mesopotamian unity of 7 planetary deities and days of the week.

Kazembek went on to become head of faculty at St Petersburg University, Firuza’s alma mater, achieving the long-held goal of making it a centre of excellence. He is revered there, as also in Kazan, to this day. As she says, by then he no longer emphasised RAS with its non-Russian associations. But he kept up his membership to the end.

Like most things Russian of the period this connects with Pushkin who visited Kazan in 1833 researching his History of Pugachov (1834). Pushkin spent time with Fuchs and his poetess wife and may well have met Kazembek and others. His friend Count V. A. Musin-Pushkin’s relative, M. N. Musin-Pushkin, the Custodian of Kazan University, certainly played an influential part in advancing Kazembek’s career. The Society will be celebrating these early shared interests in exploring all parts of Asia with a bicentennial Journal Supplement featuring Derek Davis’ translation of, and commentary on, Pushkin’s Journey to Arzrum [Erzurum] (1836).

Announcement:

All are welcome to a celebration of the life and work of RAS Fellow David Washbrook (who died on 24 January 2021) to be held in Trinity College, Cambridge, on Saturday 28 May at 2pm.