Intertextual and Material Culture: Researching the RAS Collections

This week’s blog post is by Ruth Westoby.

Handwritten on paper in Sanskrit, using devanāgarī script, is a manuscript of the Śārṅgadharapaddhati which forms part of the Royal Asiatic Society’s Tod collection. Along with many other items this manuscript was gifted to the Society by Colonel James Tod on 21 February 1824. Neither Tod’s Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan nor the two catalogues of his collection, Barnett’s in 1940 and Hooja’s in 2003, record how the manuscript came into his possession. The Śārṅgadharapaddhati is a verse anthology in Sanskrit compiled in 1363 CE near Jaipur though the RAS copy is likely to be much later, perhaps seventeenth century. The compiler, Śārṅgadhara, provides attributions for the majority of the verses in the anthology, some to famous authors such as Abhinavagupta, Bhartṛhari and Daṇḍin, and others to more obscure authors as well as to himself. The topics range from poetry (kāvya) to horticulture (vṛkṣāyurveda) and equestrian matters, making this anthology encyclopaedic in nature. The collection includes verses known as subhāṣitas or ‘well-spoken sayings’, and topics range from polished poetry to didactic instructions on yoga, as well as rather more prosaic technical instructions on the production of manure.

I am undertaking a study of this text as part of a CHASE AHRC-funded placement at the Royal Asiatic Society. This placement is an opportunity to develop research skills beyond the scope of my thesis – and complementary to it. That thesis is a genealogical textual history of the yogic body in Sanskrit sources on early haṭha yoga supervised by Dr James Mallinson at SOAS, University of London. This involves translating and studying texts in a thematic study of conceptions of the body that underpin physical yoga practices. The corpus comprises sources from the early haṭha yoga period, eleventh to fifteenth centuries, which are characterised by their relative brevity and apparent single-authorship.

The opportunity to study the extensive anthology that is the Śārṅgadharapaddhati and its intertextual relationships within the wider RAS collections is significantly broadening my research skills and extending the temporal focus of my research forward into the early modern period. Highlights of working in the RAS reading room are studying real physical manuscripts and the material culture of their production and reproduction, broader archival research to contextualise the sources, and the collection practices that have contributed to the RAS library and archives over the past almost (!) 200 years. Researching and writing a PhD is a singularly solitary process – feeling part of a thriving research culture and active archive in the centre of London is just pure geek-out fun (quite apart from being a most welcome break from the thesis!).

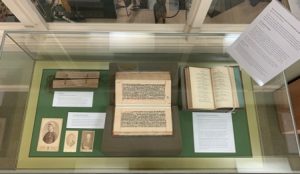

I just curated an exhibition for the RAS reading room entitled ‘Intertextual and Material Culture of the Śārṅgadharapaddhati’ to showcase the manuscript itself and items from the RAS collections connected with it. The items demonstrate the range of materials held by the RAS from the handwritten paper manuscript of the Śārngadharapaddhati to an eighteenth- or nineteenth-century CE palm leaf manuscript of the Devīmāhātmya (RAS Sanskrit ms 42 / Whish ms 41) which is part of the Mārkaṇḍeyapurāṇa, a source text for the Śārṅgadharapaddhati’s chapters on yoga. This is a Sanskrit manuscript in grantha script. A printed item included in the display is Peter Peterson’s Sanskrit edition in devanāgarī of the entire Śārṅgadharapaddhati drawing on six manuscripts. Photographs selected from the RAS photography file 24, named ‘Portraits of Orientalists’, include ‘Babu Rajinderlal Mitra’ (Rajendralal Mitra) taken in 1884, the collector Brian Houghton Hodgson taken in 1876, and the Sanskritist Monier Monier-Williams (no date). Not included in the display due to its size but included in the file is a portrait of F. Eden Pargiter (1852-1927) who translated the Mārkaṇḍeyapurāṇa in 1904. Rajendralal Mitra is the only Indian in the file and of the 39 portraits all are men. The trickiest decisions in curating the exhibit were about what had to be left out – including a stunning drawing of the temple of Dattātreya at ‘Bhátgáon’, Nepal by Raj Man Singh, 1844 (RAS Hodgson 022.047). Dattātreya is a teacher of yoga in the Mārkaṇḍeyapurāṇa and Śārṅgadharapaddhati. Whilst he is named as having mastered yoga in the yoga portion of the Śārṅgadharapaddhati verses are not attributed to him directly. Alongside Dattātreya, Markaṇḍeya is also described as a master of different types of yoga. In the yoga portion verses are attributed to the teachers Vasiṣṭha and Śārṅgadhara (self-authored) and the works the Yogaśāstras and Mārkaṇḍeyapurāṇa. Dattātreya as an ascetic and deity has a long and multifaceted history not confined to his narration of yoga teachings.

Where does scholarship on the Śārṅgadharapaddhati stand? Theodor Aufrecht and Otto Böhtlingk gave extracts and translations into German in 1871 and 1873. Peter Peterson’s 1887 edition was the first complete printed edition in Sanskrit. As yet there is no complete critical edition nor complete English translation. An intended outcome of this placement is a study of this text that analyses its teachings on yoga and its place in the history of yoga.

In the meantime, the influence of materials gathered during the placement found its way into the presentation I delivered last month at the American Academy of Religions in Denver (where the intertextuality and orality of the Śārṅgadharapaddhati, as well as the courtly production of such literature, nuanced my conclusions on rājayoga or the yoga of kings).

In addition, last week’s presentation for researchers at the consortium of institutions funded by CHASE drew on RAS materials in a presentation of manuscript materials and manuscript practices from creation to copying to recreation under the broad aegis of CHASE’s conference theme, ‘the new normal’. Here ‘the new normal’ helped me think through processes of change – of adoption of new elements, marginalisation of old – at the intersection of material manuscript culture and the history of ideas.

Ruth Westoby, December 14 2022

—

Christmas Update

The Society will soon close for the Christmas holidays. The last day that the library will be open this year is Tuesday 20 December. We would like to thank all our readers, and all friends and members of the Society, for your support over the past year. We look forward to an exciting year ahead as the Society enters its bicentenary year in 2023. For now, RAS staff would like to wish you a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year!