Oscar Eckenstein and Richard Burton

The majority of the Richard Burton Collection, now held by the Royal Asiatic Society, once belonged to Oscar Eckenstein. These were donated by Lewis C. Loyd in 1939, 18 years after Eckenstein’s death. But who was Eckenstein and why did he collect such a comprehensive array of Richard Burton publications?

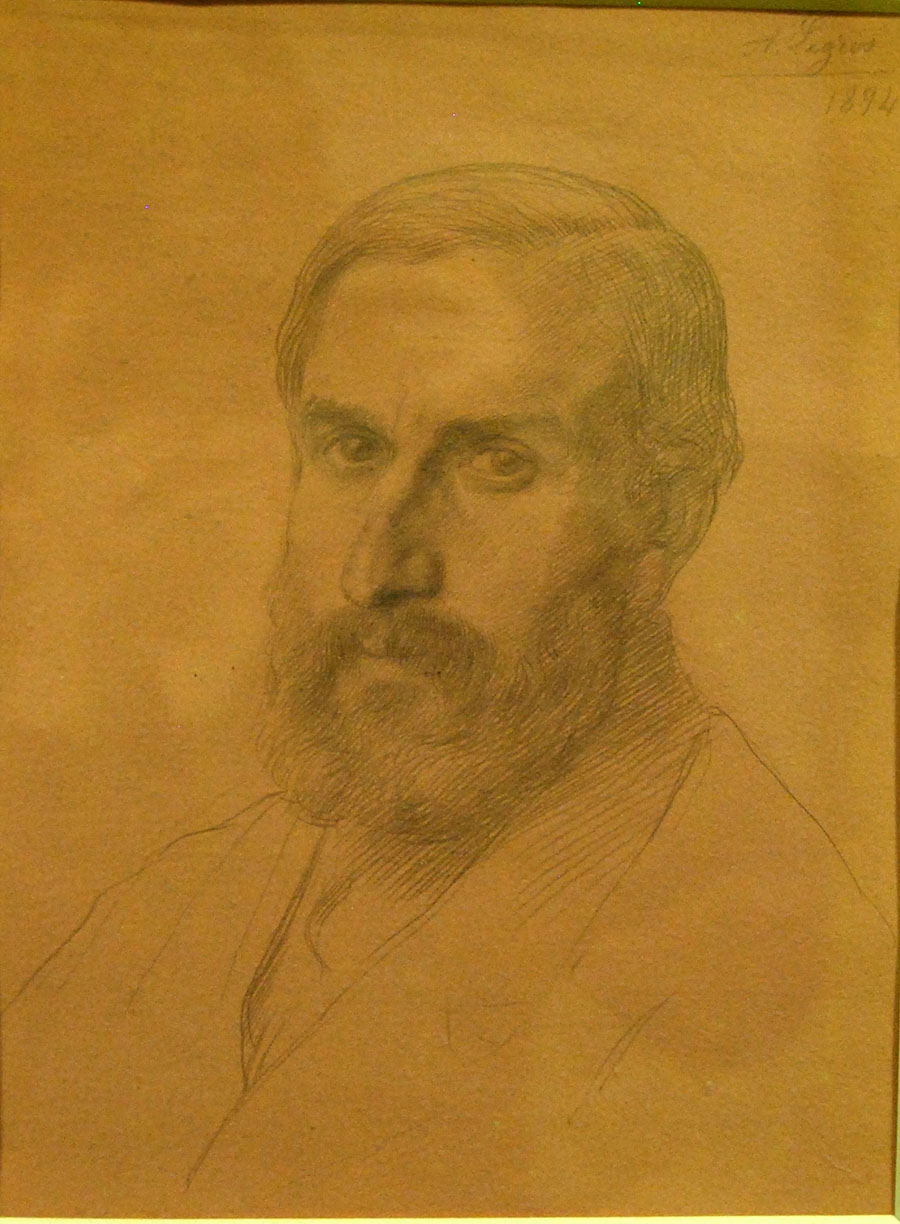

Oscar Eckenstein was born in 1859 in the East End of London, the son of a German Jewish socialist who had fled from Bonn in 1848, and an English mother. He earned his living as railway engineer, and worked for the International Railway Congress founded in Brussels in 1885. But it seems his real love was mountain climbing. He didn’t fit the mould of the typical climber at the time – the Victorian gentleman – and thus was never really accepted by, or part of, the Alpine Club. But he certainly climbed – in Wales, in the Alps, in Mexico and in the Himalayas where he was the leader of the team to make the first serious attempt to climb K2 in 1902.

Eckenstein used his engineering skills in improving mountaineering equipment. He invented a new crampon to aid in ice-climbing and devised an ice-pick that was shorter and more light-weight and therefore easier to handle. He loved to free-climb, without being roped to another climber, and could be called the pioneer of bouldering. Two of my sons were keen climbers, as school-boys, and I spent many days watching them on climbing walls as they practised bouldering techniques. Eckenstein saw it as a way of using both mind – to look for appropriate routes with suitable foot and hand-holds – and muscle – training fingers and feet to grasp small spaces. There is a boulder in Snowdonia named after him, which he used to practise all these techniques. It has been suggested that he ran the first bouldering competition whilst climbing in the Himalayas.

It also appears that Eckenstein was not an easy man to get on with and that he often quarreled with other team members, particularly if they were not willing to take the risks that he wanted. He certainly was not a fan of the establishment, who at times, tried to exclude him and prevent his climbing. This may sound a familiar story… Richard Burton, too, had little time for the establishment and was always looking for ways to circumvent their rules and instructions. In a Library Talk, given by David Dean at the Royal Commonwealth Society on November 3, 1959, Dean seeks to find the connection between Eckenstein and Burton. A copy of this talk can be found in the newly catalogued Burton Papers.

The main link seems to be found through another climber, Aleister Crowley. Younger than Eckenstein, Crowley seemed to become a friend and was certainly a partner on several of Eckenstein’s climbs. Crowley is an interesting character – at times, the press dubbed him as “the wickedest man in England”. Crowley was an occultist and magician who founded the religion and philosophy of Thelema. As such, he was possibly even more of an outsider than Eckenstein. But he was brave and willing to try new techniques and this possibly bound the two men together. It is known that Crowley was an admirer of Richard Burton. It is not known whether he sparked Eckenstein’s interest, or whether it was the other way round, but in Crowley’s book, Confessions, he praises Eckenstein’s skill and also says:

“Sir Richard Burton was my hero and Eckenstein his modern representative, so far as my external life concerned” and the dedication in Volume 2 of the Confessions reads “To three immortal memories. Richard Francis Burton, the perfect pioneer of spiritual and physical adventure; Oscar Eckenstein, who trained me to follow the trail; Allan Bennett, who did what he could.”

So Crowley, certainly linked the two men. But there does no appear to be any record of how or why Eckenstein was interested in Burton. But he certainly was – in his lifetime he collected a almost complete set of books and pamphlets including rare first editions. He had articles individually leather-bound and chased down material that came on the market. But why? Did it become a necessary hobby or compulsion as his lungs became weaker and he was no longer able to climb? Or was it a life-long passion? Perhaps, at some point, more archival material will turn up somewhere, that will shed some further light. There is within our own archive two carbon-copy books of letters between Eckenstein and Norman Mosley Penzer, the orientalist and Burton authority. These letters are ostensibly about the possibility of Eckenstein selling his collection to Penzer, but a detailed reading may give some clues on the source of Eckenstein’s passion.

We at the RAS, and the many researchers who have had access to the Richard Burton materials, have much to be grateful for from the collecting habit of Oscar Eckenstein, engineer, inventor and climber.