Robert Skelton OBE (1929-2022) / A Summer Sojourn in Italy: Making a Chinese Qur’an

ROBERT SKELTON OBE (1929-2022)

We were very sorry to learn that Robert Skelton, the distinguished art historian and former Keeper of the Indian Department at the Victoria and Albert Museum, died on Monday, 22nd August. His deep interest in the arts of North India and the Deccan, particularly during the later medieval and Mughal periods, resulted in many publications. He was a loved and generous mentor to generations of students and will be sorely missed by all those that knew him. His infectious enthusiasm and extensive knowledge made him a magnet for colleagues and students across the globe, many of whom he welcomed to his home in Croydon. Above all, he was excellent company, happy to share anecdotes while showing genuine interest in others and their research. He was a long-standing and cherished member of the RAS and the Society sends its heartfelt condolences to his family and friends at this very sad time.

————————————————————————————————-

REINSTATE THE POST OF PROFESSOR OF BURMESE AT SOAS

It has come to our attention that the position of Professor of Burmese at SOAS is to be discontinued. In response to this decision, a petition has been organised by ANU to request that the position be reinstated.

Your support in this matter would be greatly appreciated as this means that Burmese courses will no longer be available at university level in Britain. Burmese has been part of the SOAS curriculum for over 100 years and Professor Watkins has been shouldering sole responsibility for the department since the death of John O’Kell in 2020.

The ANU petition can be accessed here Reinstate the post of Professor of Burmese at SOAS, University of London

A Summer Sojourn in Italy: Making a Chinese Qur’an

Every year, during the months of July and August, bookbinders, conservators, art historians and bibliophiles wend their way to a small town in Lazio called Montefiascone to attend bookbinding courses organised by the Montefiascone Project. This is a non-profit making organisation, set up in 1988 by Cheryl Porter (RAS fellow, book conservator) with Dr. Nicholas Barker, (formerly Head of Conservation and Deputy Keeper at the British Library) to fund the restoration of the Library of the Seminario Barbarigo.

The library was established by Marc Antonio Babarigo (1640-1706), a member of a famous Venetian family, who was elected cardinal and appointed Archbishop of Montefiascone and Corneto. The earliest inventory of the library was compiled in 1692 and it consisted mainly of theological works and books on Canon Law. However, in 1706, more books were added by Cardinal Babarigo, some dating back to the 15th century, including rare editions of the Aldine Press in Venice that had belonged to his ancestor Pierfrancesco Babarigo, an important investor in the press. Books also arrived from other libraries including some in Hebrew and Syriac as well as a rare copy of the polyglot Walton Bible printed in 6 folios and nine languages between 1654-7. The library was neglected for many years as the collection no longer provided relevant reading matter for seminarians. During the Napoleonic invasion of Italy, some of the books were even used for target practice and they still bear the scars left by the lead shot. The seminary bathrooms, positioned above the library, then flooded sometime before 1988 which had a devastating effect resulting in widespread mould and water damage. The bodies of mummified rats and birds’ nests were also found among the volumes that somehow survived these tragedies. Thanks to the work and devotion of Cheryl and those who have graciously volunteered their time during the summer for the past twenty-four years, the library has risen from the ashes. Today, the books are in pristine condition, boxed, conserved and are in the process of being catalogued.

The collection has many rare gems including volumes which contain the seminary’s accounts providing a bird’s eye view of the daily dealings and activities over the centuries. This is in essence an early file folder, as extra sheets of paper could be added each year.

Each year courses are held on different structures by conservators from all over the world. I was asked by Cheryl in 2012 to give a lecture to set the context for a Mamluk binding course and since then I have continued to play a small part in the Islamic binding series. Since I have been attending Montefiascone I have made, with a lot of help, a Mamluk binding, an Ottoman embroidered binding, an Indo-Persian stamped binding (all taught by Kristine Rose Beers, Head of Conservation at the Chester Beatty Library), a small Mudejar binding (taught by Ana Beny) and a Renaissance ‘alla islamica’ binding (taught by Jim Bloxam, formerly Head of Conservation, Cambridge University Library and Shaun Thompson, Deputy Head of Conservation, Cambridge University Library) to name but a few. Other courses address different binding traditions and structures.

Chinese Qur’ans

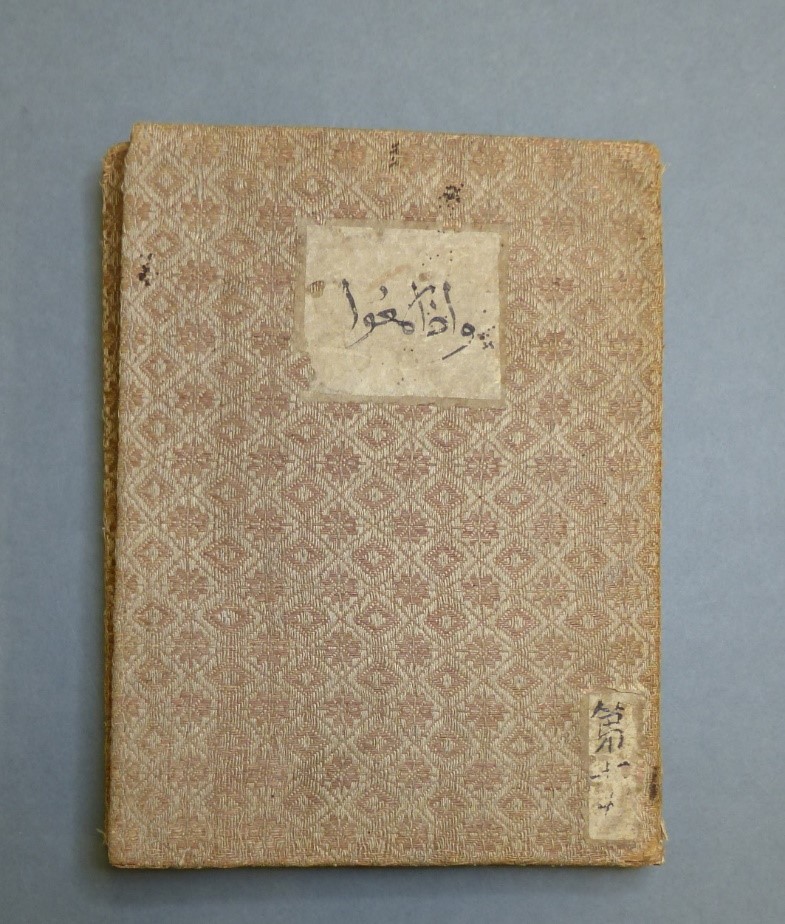

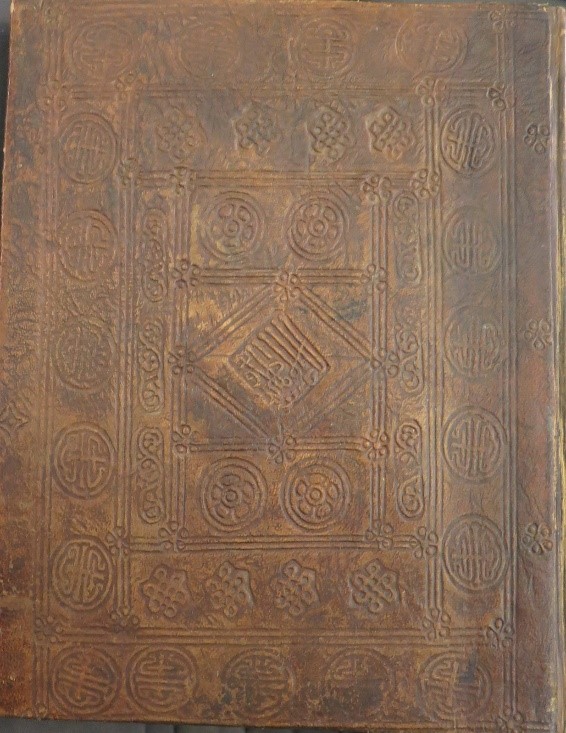

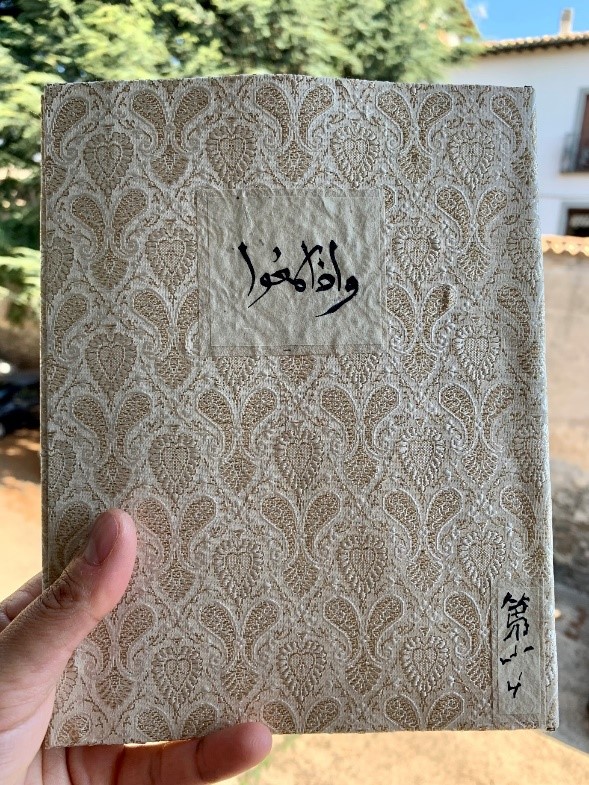

This year we produced a replica of the binding of a Juz’ (part) of a Chinese Qur’an dateable to the 19th century, the original being in the Chester Beatty Library Dublin (CBL Is 1602) The course was taught by Kristine Rose Beers aided by Cécilia Duminuco.

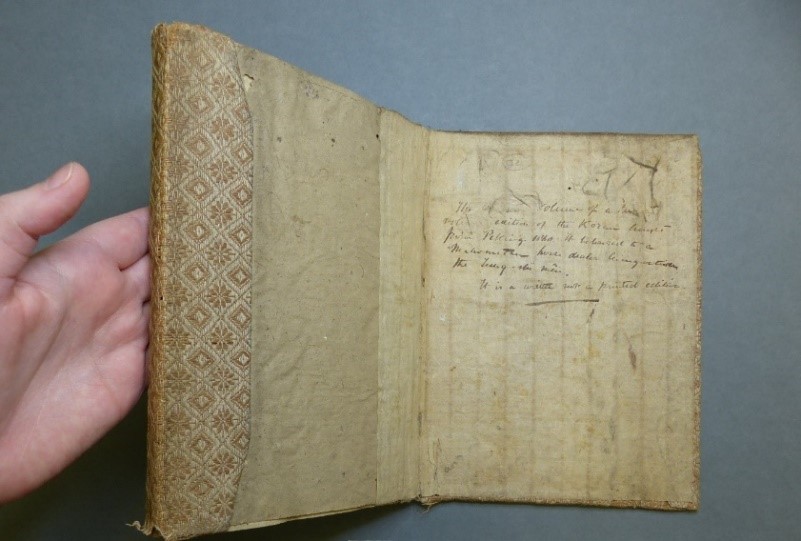

The label at the centre of the upper cover, written in Arabic, gives the first 3 words of Juz’ 7 which is taken from verse 83 of Sura al-Ma’idah. (I would like to thank Marcus Fraser and Tim Stanley for their help in deciphering this. For those who are interested, the letter sin is rendered as a diagonal stroke).

Q وَإِذَا سَمِعُوا۟ مَآ أُنزِلَ إِلَى ٱلرَّسُولِ تَرَىٰٓ أَعْيُنَهُمْ تَفِيضُ مِنَ ٱلدَّمْعِ مِمَّا عَرَفُوا۟ مِنَ ٱلْحَقِّ ۖ يَقُولُونَ رَبَّنَآ ءَامَنَّا فَٱكْتُبْنَا مَعَ ٱلشَّـٰهِدِينَ

When they listen ( These are the 3 words) to

v.83 When they listen [These are the 3 words shown on the label] to what has been revealed to the Messenger, you see their eyes overflowing with tears for recognizing the truth. They say, “Our Lord! We believe, so count us among the witnesses.

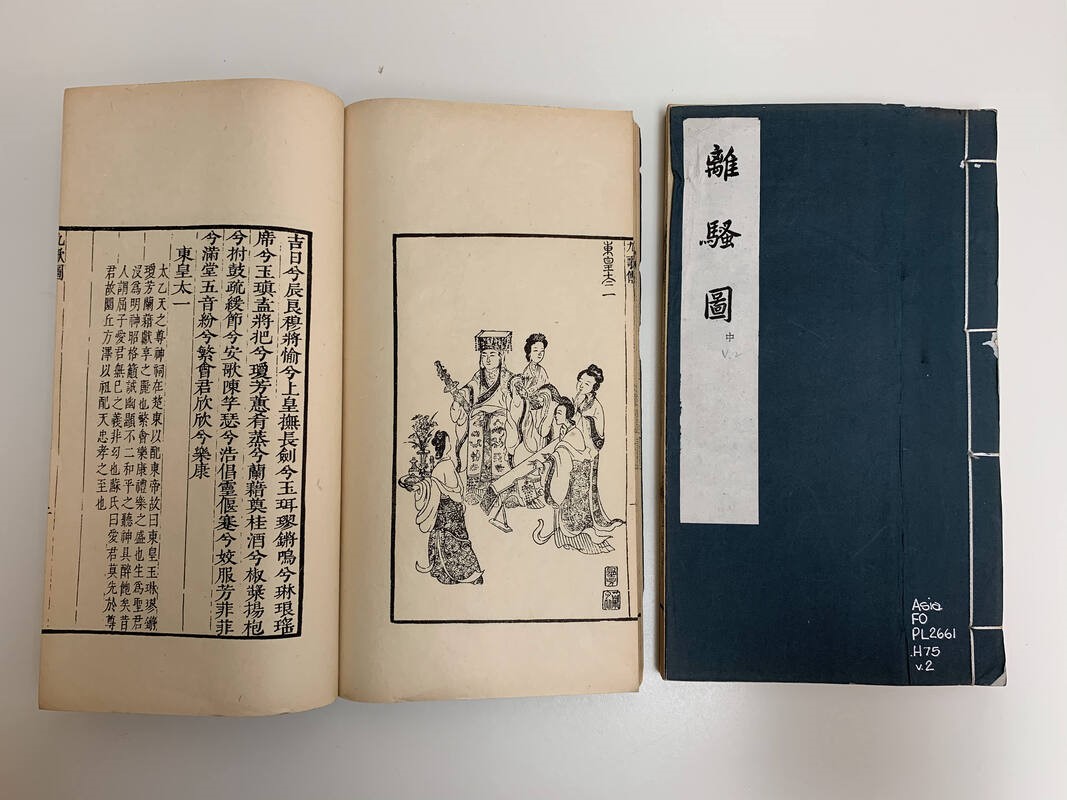

The format and structure follow that of an Islamic binding and manuscript providing a defined link with the Islamic tradition and standing in stark contrast when compared to the typical thread binding used for Chinese texts from the 14th to the early 20th centuries.

In the Chinese Qur’an, the sections of the text block are sewn using a link stitch and are then pasted into the covers according to the Islamic binding tradition. A flap protects the textblock, albeit with slightly different profile when compared to the typical envelope flap found on bindings produced in the Islamic west. The head and tail of the spine are provided with candy stripe endbands woven in silk. An inscription tells us it was bought from a horse dealer living outside Teng Shi Men in Peking in 1860.

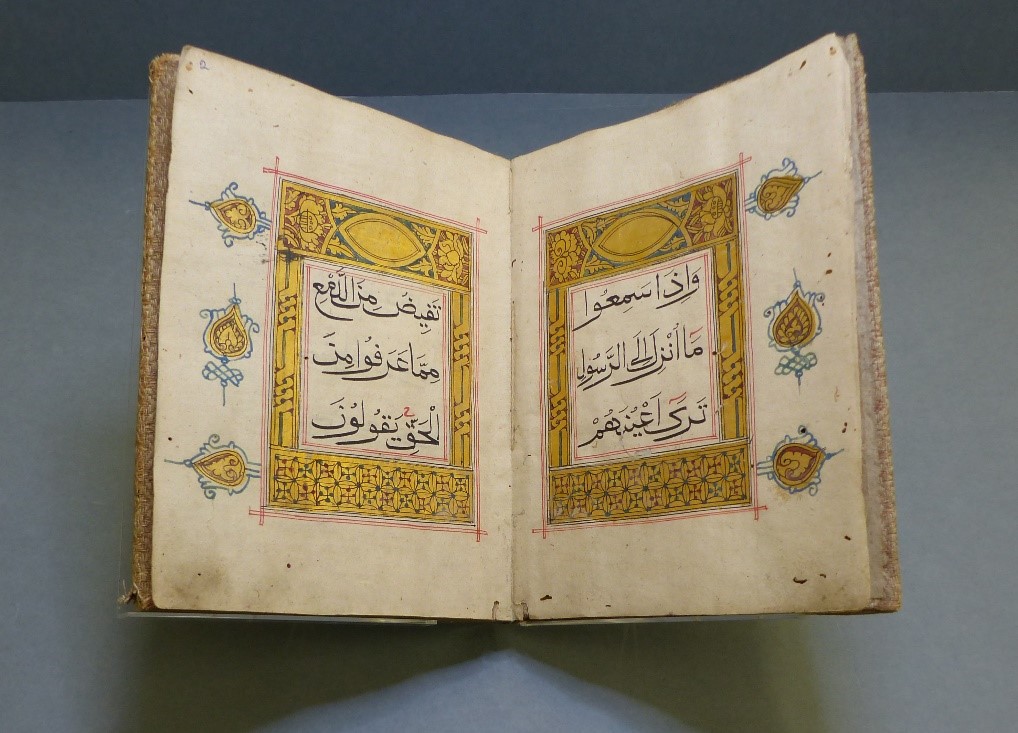

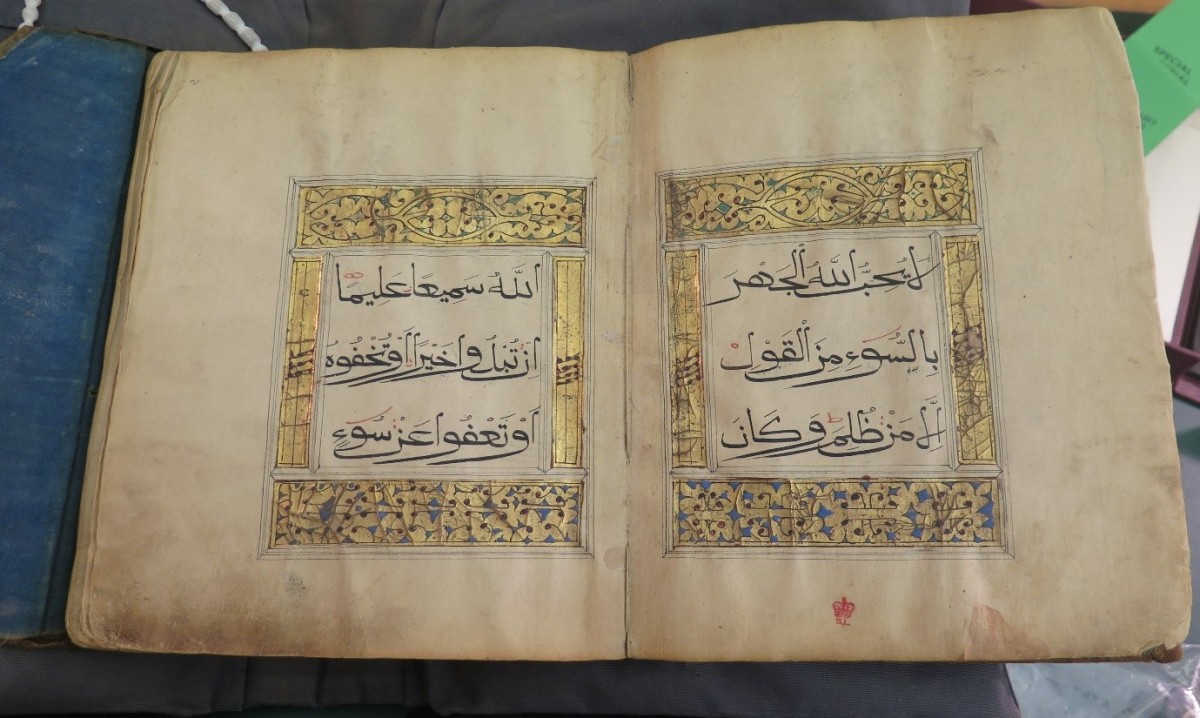

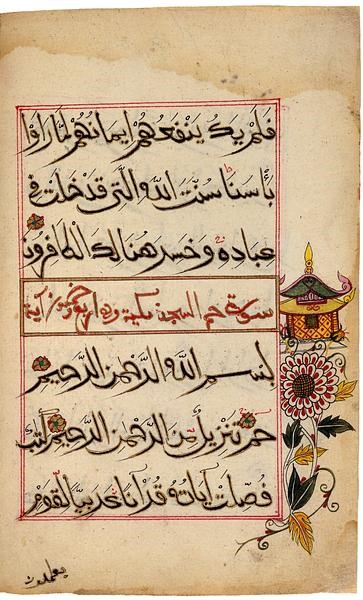

The opening and final pages are illuminated with panels containing the text. The decoration consists of rectangles divided by intersecting arcs of circles and on either side of the panel, the border is made up of, what we might term, coiled stanchions. The text is written with a reed pen using a form of muhaqqaq, a script that was commonly used for the copying of Ilkhanid and Mamluk Qur’ans. The style of script is often referred to as sīnī (Chinese in Arabic)

Marcus Fraser, in his article on Chinese Qur’ans[1], makes the point that until recently Chinese Qur’an manuscripts were relatively unknown in Western collections. The example above was acquired by Alfred Chester Beatty in 1962 from the Maggs Brothers, the rare book dealers. The only substantial studies of Chinese Qur’an manuscripts in English that exist to date are by Marcus Fraser and Tim Stanley who discussed the Qur’ans in the Khalili Collection.[2]

Muslim communities have been established in China since the 7th century. According to the historical accounts of Chinese Muslims, Islam was first brought to China by Sa’d ibn abi Waqqas, the uncle of the Prophet Muhammad who came to China for the third time at the head of an embassy sent by Uthman, the third caliph, in 651. He later died there and his tomb still exists in Guangzhou. Although scholars have not found any historical evidence that Sa`d ibn Abi Waqqas visited China, they agree that the first Muslims must have arrived in China sometime in the 7th century, and that the major trading cities, such as Guangzhou and Quanzhou probably already had their first mosques built during the Tang Dynasty (618-907), although no reliable sources attest to their actual existence.

Today, the Muslim population of China is estimated as representing 0.45% to 2.85% of the total population, with 39,000 mosques serving this congregation. The Muslim population in China is basically divided into two groups: the Uighurs, a Turkic group who live for the most part in northwestern China and the Hui whose ancestors came to China as merchants, soldiers and scholars from Persia and Central Asia who over the centuries intermarried with Han Chinese.

By the 8th century Muslim merchants were already trading in China and a community was known to have been established in Xian where a mosque was built in 742. However, the impact of Islam was not strongly felt until several centuries later during the Song (960-1279) and Yuan (1279-1368) dynasties when the network of trade routes known as the Silk Road became the conduit for the spread of religious and cultural influences as well as goods and merchandise. The origins of Islam in China remain shrouded in mystery but what can be established is that Muslim trading communities were firmly established along the coastal areas of China by the 9th century. During the Yuan period (1279-1368) Muslims were able to hold privileged positions in the bureaucracy and it is estimated that 4,000,000 Muslims were then present in China. However, when the Yuan were overthrown by the Ming, they lost these positions and many left as they were now excluded from government service.

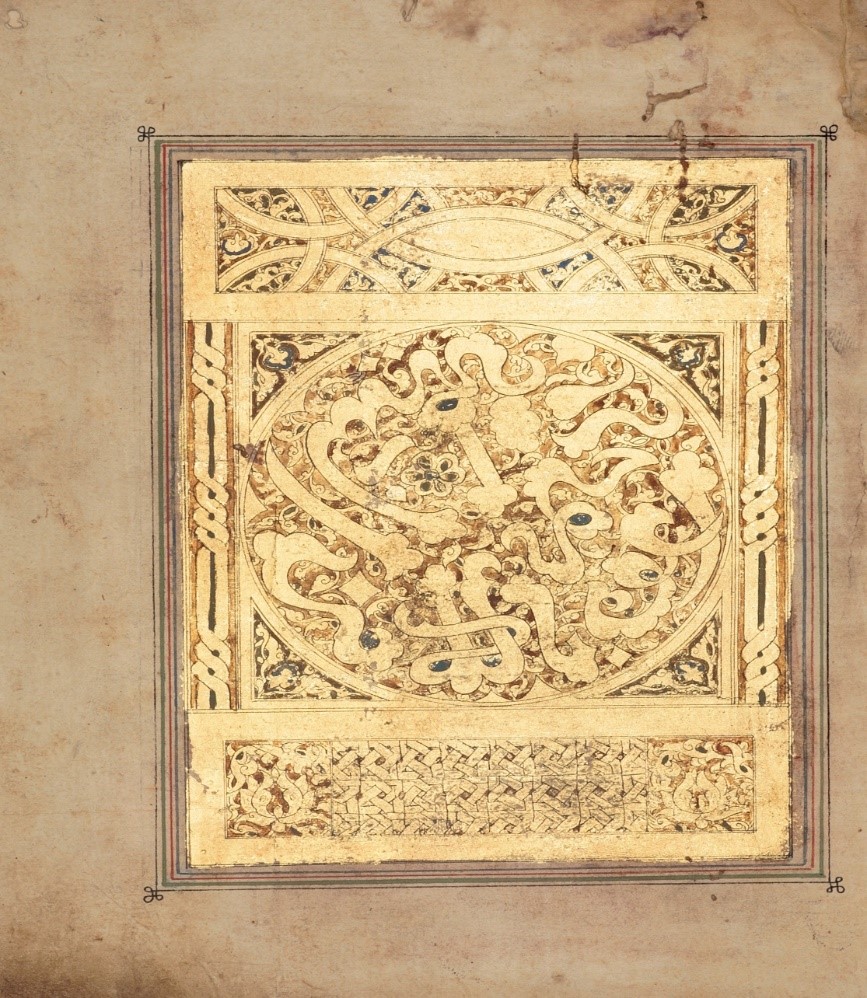

The earliest surviving Chinese Qur’ans date from the 15th century. The example below is from the Khalili Collection and was completed by Hajji Rashad ibn Ali al-Sini on the last day of Muharram in the year 804 in the Great Mosque of Khanbaliq later to become Beijing in 1421. The manuscript opens with the roundel bearing the words: أعوذُ بِٱللَّهِ مِنَ ٱلشَّيۡطَٰنِ ٱلرَّجِيمِ, (I seek refuge in God from Satan, the accursed) with the Arabic letters appearing in cloud-like forms. In this early 15th century Qur’an, the same intersecting arcs and coiled stanchions appear in the illumination as in the 19th century example from the Chester Beatty. In looking at other examples in the British Library, the same ornamental devices are used over and over again, an indication of the conservatism that imbued Qur’an production in China. Please see British Library Blog: https://blogs.bl.uk/asian-and-african/2017/08/illumination-and-decoration-in-chinese-qurans.html (I would like to thank Colin Baker and Daniel Lowe of the British Library for allowing me to take some images of the Qur’ans).

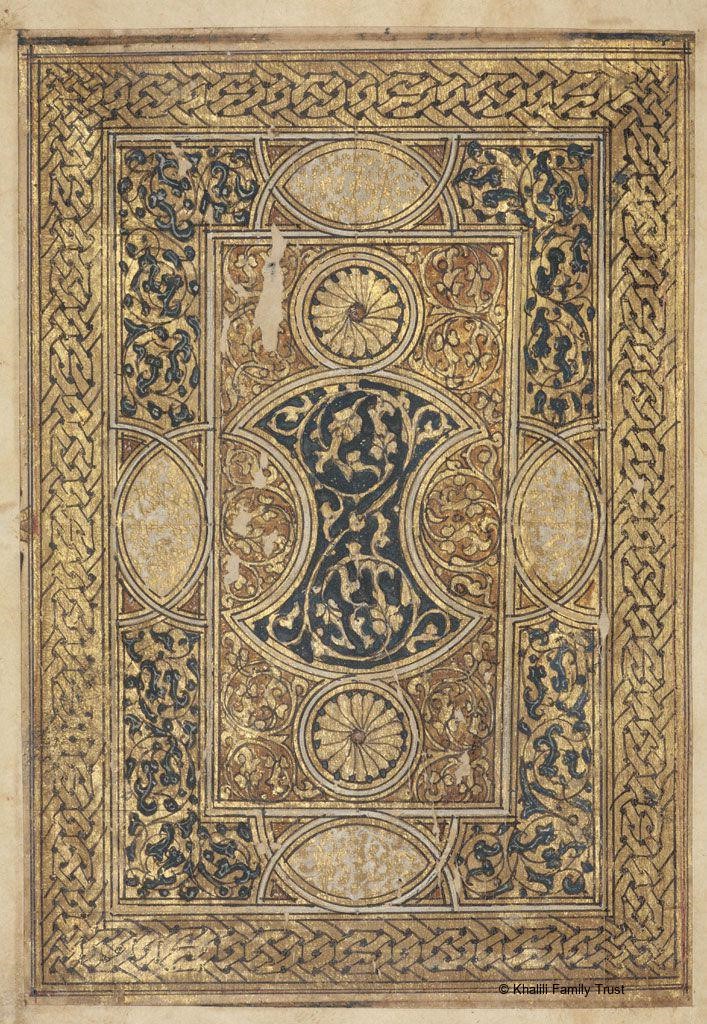

Segmented arcs were used in the illumination of Ilkhanid manuscripts as in the page of this Qur’an illustrated below copied by Yaqut al-Mustasimi (d.1298), the famous calligrapher who established the form of the 6 scripts used throughout the Islamic world from the 14th century. As Fraser points out the illumination of Chinese Qur’ans relates to Ilkhanid work and was derived from what he calls the ‘foundational’ copies that reached China in the 13th and 14th centuries. The demise of the Yuan dynasty in 1368 resulted in a decline in the Muslim population and restricted contacts with the Islamic west. In order to retain their identity, the Muslim communities in China sought to cling to their heritage retaining the format and styles of early Qur’ans in their possession.

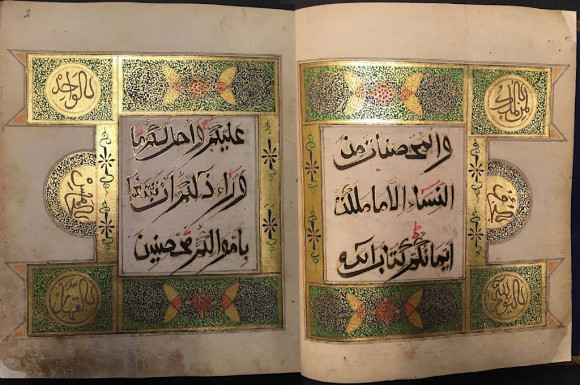

However, by the Qing dynasty (1636-1911) increased sinicisation can be noted in the decoration and format of the Qur’ans. This 18th century Qur’an in the British Library, illustrated below, is a good example. The illumination in a bright palette of red, yellow, gold and green; painted to achieve a mottled effect still betrays its Islamic origins in the formatting of the page but the ornamental elements of interlocking segments and braided stanchions have now been transformed.

Likewise, although the binding retains a flap, it has a scalloped profile and the cover with the bismillah stamped at the centre is in the form of a Chinese seal.

Another charming example is a Qur’an page from the David Collection in Copenhagen copied in Beijing by a lady calligrapher, Ama Allah Nur al-Ilm, the daughter of Rashid al- Din in 1643. The borders decorated with flowers and small pagodas show the inclusion of Chinese decorative elements.

The Course

We met every morning in the Magna Aula of the Seminary and spent until early afternoon pasting, sewing, cutting under the watchful gaze of Kristine and Cécilia along with a number of distinguished church dignitaries whose portraits are arranged around the room. This year we were joined by enthusiasts from Belgium, Canada, Egypt, Hungary, the Netherlands, Singapore, the United Kingdom and the USA. By the end of the week we had produced a book.

However, not all the time is spent bookbinding. Montefiascone soars above Lake Bolsena, the largest volcanic lake in Europe, perched on the rocky summit of Mount Falisco. Afternoons are often spent swimming, visiting other towns nearby such as Orvieto or Bagnoregio, ‘the dying city’ or the mozzarella farm where the buffalo are tended by Punjabi Sikh farmers in turbans.

We celebrated the Feast of San Lorenzo on the 10th August when shooting stars (the Perseids, small meteors from the constellation of Perseus) populate the skies. San Lorenzo is the patron saint, quite appropriately from our point of view, of librarians and booksellers (as well as pastry chefs, vermicellai, firefighters, caterers and glass workers). According to legend, the shooting stars represent the embers from the grill on which the poor saint was burned under the edict of the emperor Valerian who condemned to death all Christian bishops and deacons.

The month of August is also when Montefiascone holds its wine festival ‘Est Est, Est.’ The legend is that a German prelate, Johannes Defuk, on his way to Rome in the 11th century, sent his servant ahead to identify the best towns for food and wine. On arrival at a town, the servant was meant to record his opinion by writing ‘Est’ on the door of the chosen tavern (a shortened version of Est bona) but when he reached Montefiascone so amazed by the quality of the food and wine, he wrote ‘Est, est, est’ on the chosen tavern door. Defuk returned to Montefiascone on his way home from Rome and died, it is believed, of overindulgence. He is buried in the 11th century church of St. Flaviano just outside the town’s walls. The procession is enacted several times during the festival with the townspeople of Montefiascone playing various roles. Every night there is musical entertainment with al fresco meals arranged by the town hall accompanied by wine tastings… So, un meraviglioso soggiorno estivo in Italia.

[1] Marcus Fraser, ‘Beyond the Taklamakan: The Origins and Stylistic Development of Qur’an manuscripts in China’, in ‘Fruit of Knowledge, Wheel of learning, Essays in Honour of Robert Hillenbrand, ed. Melanie Gibson, London, 2022, pp. 180-200

[2] Tim Stanley, ‘Qur’ans of the Ming Period’, The Decorated Word, Qur’ans Manuscripts of the 17th to 19th centuries, eds Manijeh Bayani, Anna Contadini and Tim Stanley, London, 1999, pp.12-24.