William Carey and the Serampore Trio

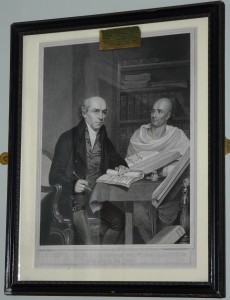

Today, 9th June, marks the anniversary of the death of William Carey. Born in 1761, he died on this day in 1834. Having spent most of my childhood in Northamptonshire, Carey was an important part of my local history. But it was only when I joined the RAS as the archivist, I discovered more of his contribution to the study of Asian culture and language. In our Lecture Hall we have an engraving of Carey with his pundit, Mritunjaya, by W. Worthington from a portrait by R. Home.

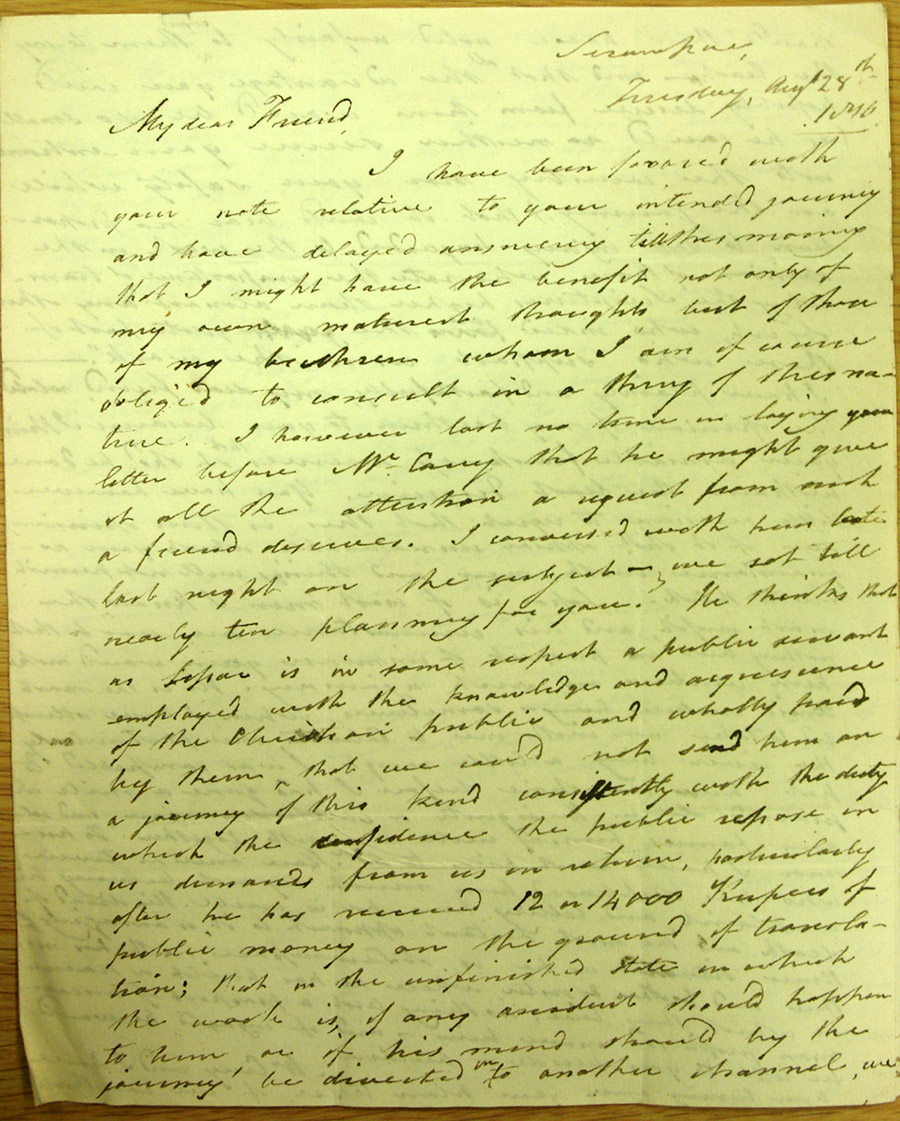

Along with William Ward and Joshua Marshman, William Carey comprised the “Serampore Trio”, three Baptist missionaries based in the town of Serampore, near Calcutta, in the early nineteenth century. The three men were British, but they resided in Serampore, a Danish colony, because at that time the East India Company prohibited British missionary work in the regions under its influence. One of the main objectives of the Serampore Trio was to translate the Bible into vernacular languages, so that scripture could be more easily accessed by people in India and elsewhere in Asia. Below, the Society’s Librarian, Edward Weech, describes some of Joshua Marshman’s correspondence, which can be found in the RAS Archives:

“In 1810, the English scholar Thomas Manning arrived in Calcutta, hoping to enter China from India. At that time, Europeans were strictly prohibited from entering the Chinese empire by its Qing government. Manning eventually tried to enter China via Tibet, getting as far as its capital, Lhasa. Manning was the first Englishman to visit Lhasa and, while he was there, he was lucky enough to have several meetings with the young Dalai Lama.

But before he left India for Tibet, Manning became acquainted with Joshua Marshman, who was at that time trying to translate the Bible into Chinese. In the early 1800s, hardly anyone in Britain knew anything about the Chinese language, and so the arrival of Manning – who had studied Chinese, albeit briefly, in Canton (Guangzhou) – in Calcutta was a major event, providing a great opportunity for Marshman. Marshman therefore solicited Manning’s help with his translations, and his requests for help and advice are contained in the series of letters to Manning which can now be found in the Society’s archives. These have been digitized and are available to view online, via the RAS Digital Library (RAS TM 5/19).

The relationship was not all one-way, however, and Manning sought Marshman’s help, too. For his Chinese translation work, Marshman relied on the assistance of an Armenian man, Johannes Lassar, who had been born in the Portuguese colony of Macao. There, Lassar would have learned to speak Cantonese, and judging by his literary work he must also have learned at least some written Chinese. Marshman’s letters show that Manning enquired whether he might recruit Lassar as an assistant for his own journey to China. In the end, Manning instead recruited a Chinese Catholic, Zhao Jinxiu, who was working in a wine shop in Calcutta, to accompany him into Tibet as his assistant. But that is a story for another day!

Marshman’s letters to Manning make for interesting reading. Today, it can be hard for people to relate to what missionaries like the “Serampore Trio” were trying to achieve. But Marshman’s letters provide evidence not only of his religious devotion and scholarly erudition; they testify as well to his humility, self-awareness, and even humour. When Manning floated the idea of trying to enter China through Burma, Marshman cautioned him against it, on account of the landscape and its natural hazards: “a great part of the country which you pass is complete jungle, and they (the tygers) discover no partiality to literary men.” Marshman continued:

I only add if I had Pacolet’s wooden horse I would take you up and put you down in the midst of Pekin, and after staying with you a month or two turn the pin and remain at Serampore till your talisman reminded me you were ready for your return, when I w[oul]d fetch you hither with all imaginable safety.

“Pacolet’s horse” is a now-obscure reference to a magic horse that featured in the early French romance Valentine and Orson, which could transport its owner anywhere he wanted to go. It was referred to by the Elizabethan poet Sir Philip Sydney in his Defense of Poesy, and this is perhaps the likeliest source for Marshman’s own use of the image. Manning – who personally knew major English Romantic writers including Samuel Taylor Coleridge, William Wordsworth, and Charles Lamb – was, like other Romantics, an enthusiast for English Renaissance literature. As well as the works of Shakespeare, this genre encompassed the poetry of Sidney and Edmund Spenser, as well as the plays of Christopher Marlowe, Beaumont and Fletcher, and many others. Marshman’s use of this image gives us a hint as to the kind of thing that might have informed their conversation during their occasional meetings in Calcutta; that is, whenever Marshman could restrain himself from asking Manning’s advice about his translations into Chinese!”

My thanks go to Edward for providing these fascinating insights into these gentlemen based in Serampore. It is obvious from Marshman’s letters that he respected Carey and valued his opinion and advice. For those of you interested in finding out more about the Serampore Trio, within our Library Collections is a copy of “The life and times of Carey, Marshman and Ward: embracing the history of the Serampore mission” by John Clark Marshman. This is also available on the website of the William Carey University.

It’s International Archives Week this week, so it is with great pleasure that I can also write that the latest blog post on the Explore Your Archives website is by Edward and is an informative read about our own Digital Library and about digitisation in general. Do take time to read more of his insights.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

In other news we would like to advertise this event being held by RAS Beijing:

Prof. Ezra Vogel on China-Japan Relations: How did we get here, and where do we go from here?

RAS Beijing Zoom talk, 10 June 9pm (Beijing Standard Time)