The History of (Lap)dogs in China – post by 2023 Staunton Prize winner Dr Kelsey Granger

The Society is delighted to award the 2023 Sir George Staunton Prize for outstanding article to Dr Kelsey Granger for her submission entitled From Tomb-Keeper to Tomb-Occupant: The Changing Conceptualisation of Dogs in Early China, which was published in the JRAS earlier this year (Vol. 3, Issue 33). The article is Open Access and so is also available to non-subscribers here.

Dr. Kelsey Granger is an Alexander von Humboldt Foundation Postdoctoral Fellow affiliated with Ludwig-Maximilian University, Munich. In this role, she is researching the social significance of horses in early Chinese postal stations like Xuanquan alongside Prof. Armin Selbitschka. Her doctoral project, completed at the University of Cambridge in 2022, centred on the phenomenon of lapdog-keeping among Tang and Song elites (i.e., c. 600–1200) as well as the practice’s remarkable Silk Road connections. Related canine research has been published in the Bulletin of SOAS.

Dr Granger will be giving a talk to the Society early next year. In the meantime she has kindly produced the following post to pique your interest and introduce some of the main themes of her research.

The History of (Lap)dogs in China

Dr. Kelsey Granger, Ludwig-Maximilian University Munich

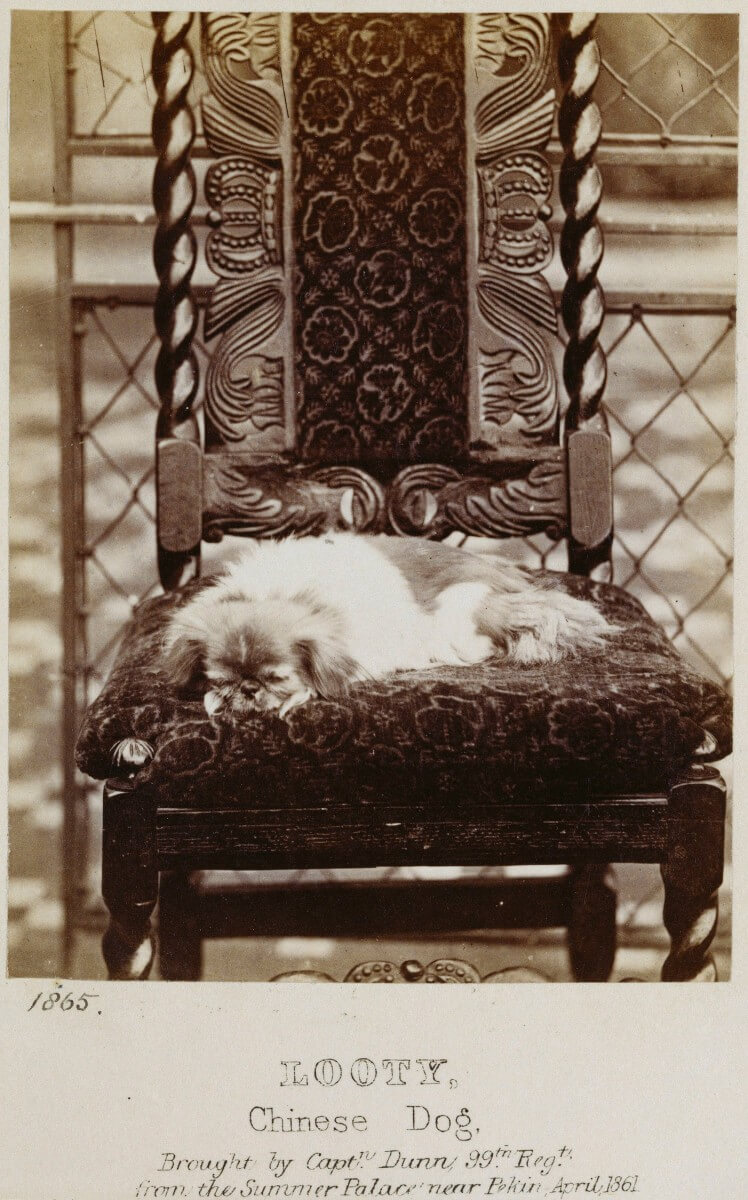

Whenever I introduce my doctoral project, completed at the University of Cambridge in 2022, to fellow Sinologists, it never fails to raise eyebrows. The history of lapdogs is, surprisingly, an understudied phenomenon in Chinese animal studies. That is not to say that attempts have not been made, with Victorian British dog-fanciers producing reams of well-meaning, though terribly inaccurate, histories tracing the lineage of the modern-day Pekingese back into the distant past. Much like Queen Victoria and her Pekingese dog Looty, purportedly stolen from the ransacked Summer Palace, emperors from time immemorial all had their ‘palace dogs’, and the dogs have not changed an iota in the millennia since! In the realm of Sinology, scholars like Edward Schafer and Berthold Laufer were more cautious, believing that lapdogs entered the scene in the Tang 唐 dynasty (618–907). In the twenty-first century, Chinese Sinologists have only just begun to write cursory articles about the many Tang poems, paintings, and ceramics featuring these small, aesthetic dogs. Despite this, the wider history and social significance of Chinese lapdogs and lapdog-keeping remains just as vague and just as vaunted as in the early 1900s.

I myself became intensely curious about lapdogs in Chinese history when watching the annual Cruft’s Dog Show with my own beloved lapdog Birdie, a Japanese Chin. Cruft’s official breed information stated that these dogs were traded between Japanese and Chinese princesses during the Tang dynasty. This struck me on two levels: first, that lapdogs were considered to be prestige goods during this zenith of Silk Road exchange, and second that women were primarily engaged with lapdog-keeping. During my M.A. at SOAS, London in 2017–2018, I wrote a short paper on lapdogs in the famed silk painting ‘Zanhua shinü tu’ 簪花仕女圖 (Picture of Ladies Wearing Flowers in their Hair), wherein two lapdogs frolic among elegantly-dressed court ladies, but this ultimately left me with more questions than answers. Why were lapdogs included in this garden scene? How come the association between lapdogs and women was decidedly positive, when women being connected with other animals was so often negative (consider the seductive fox-woman and weretiger)? And what did the lapdog ultimately mean in literature and art from this period? After a four-year Ph.D. studying lapdog-keeping in the Tang and Song 宋 (960–1279) dynasties, I feel I can finally answer some of these questions (and many others that arose along the way). And yet even still, the social and economic relevance of medieval Chinese lapdog-keeping continues to astound me.

Much as Laufer and Schafer suggested, lapdogs arrived suddenly in China sometime in the mid seventh century, when official records state that the oasis kingdom of Turfan gifted a pair of small dogs that could perform tricks to the Tang court. Elite women were the primary keepers of lapdogs during the Tang period, being described as coddling and toying with them in their chambers. It was in these female-occupied areas of the house that young boys and adolescent girls encountered the diminutive dogs, often at risk of being bitten (in one story, a boy even loses his penis to a vicious lapdog!). The reality of lapdogs being so inextricably tied to female bodies and spaces was translated into a number of paintings, ceramics, stories, and poems. This even extended, perhaps not surprisingly, to erotic Tang poetry and paintings, wherein the lapdog was a scintillating marker of private female chambers and implied sexual intimacy.

To prove that these diminutive, playful creatures really were the first lapdogs in the Chinese textual and artistic record, I had to delve much further back into the past than I had initially anticipated. Dogs in a general sense appear time and again across the full range of Chinese history, most often in association with guarding, hunting, and – perhaps surprisingly for non-Sinologists – graves. Scouring archaeological reports and anomaly tales alike for lapdogs drew my attention to a much more widely-studied aspect of Chinese canine history: dogs in pre-imperial Chinese tombs. My initial findings were published as a video essay with Trinity College, Dublin, available on YouTube here:

As my more recent article with the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (‘From Tomb-keeper to Tomb-occupant: The Changing Conceptualisation of Dogs in Early China’) discusses, the motivation behind placing dead dogs in pre-imperial Chinese tomb pits and, most especially, yaokeng 腰坑 (pit directly below the deceased’s waist) remains open to interpretation. The theory of yaokeng dogs being companions-in-death can largely be challenged by the extremely juvenile age of the buried dogs, suggestive of an industry raising puppies for imminent sacrifice. These yaokeng death attendants instead may have had geomantic, protective, or weather-appeasing ritual significance. What remains certain is that these dogs acted as ritual furniture in the tomb, being sacrificed and buried in the yaokeng during the construction of the tomb.

Keeping dogs as ‘companions’ is not particularly evident in pre-imperial or early Chinese sources. Nonetheless, the social significance of prestige hunting hounds may have motivated the burial of certain dogs in coffins within the tomb chamber, wherein the dogs wear golden necklaces and other accessories. Again, it is highly doubtful that these dogs were ‘beloved pets’, given that these atypical burials instead mirror other luxury, prestige goods. Instead, these dogs were likely socially-significant hunting hounds, perhaps even acquired from afar.

Guarding, too, was increasing relevant in the Eastern Han 東漢 (25 CE–220 CE) period, during which time the size of estates grew. Tombs from this period often feature ceramic houses, granaries, and farmsteads which were thought to provide the deceased with income and sustenance. The gradual trend towards figurines replacing sacrificed bodies and items in tombs even extended to dogs, with Eastern Han tombs being replete with barking, harnessed ceramic dogs among these domestic scenes. Since these ceramic dogs were positioned similarly to living guard-dogs, they may have been protecting the property of the deceased rather than the ritual space of the tomb. This new interpretation of ceramic dogs in tombs highlights how representations and bodies of dogs were altered in tomb iconography to mirror changing attitudes to what tombs were and what items within tombs meant. Here, in particular, hunting and guard-dogs reflect the increasing relevance of dominion, property, and ownership in the Eastern Han period.

Dogs, however, were by and large not supposed to have their own tombs. Han dynasty texts suggest that dogs and horses alike could be buried after their death given that they labour for humans much like servants do for their masters. However, such burials ought to be frugal – as Confucius supposedly advocated. Nonetheless, the discovery of a Xin 新 dynasty (9 CE–25 CE) dog’s tomb replete with many ceramic figurines suggests that these burials were perhaps not as economical as Confucius suggested. Nevertheless, these luxuries are more reflective of the human’s social status than any kind of affection for the dog itself.

Emotionally-motivated dog burials came later, at least as far as textual sources indicate, alongside a growing trope for loyal dog narratives. During the chaotic post-Han period, dogs were simultaneously vilified and commended in anomaly accounts – being both sinister figures that could transform into humans to do evil and loyal companions willing to do anything to rescue their beloved masters. Should the dog die while performing an impressive feat of bravery, they were to be buried in lavish, humanised burials that far exceeded the frugal admonishments of Confucius. While no dog burials have yet been found from this timeframe, texts certainly suggest that burying dogs in a tomb of their own reflected a growing appreciation for anthropomorphised canine morality. Returning to the Tang period, the death of one Madam Lü’s beloved lapdog prompted an even more emotionally-laden burial. After many supernatural hijinks in the underworld, Madam Lü buries her lapdog Patches (Huazi 花子) with the rites of a child – something that would perhaps not be amiss in today’s pet culture!