Reading Room is Re-opening

We are pleased to announce that from Thursday 23 July our Reading Room will be re-opening for researchers to visit. Initially we will only be open one day-a-week on Thursdays from 10.30-4.30. Providing free public access to our historic collections is one of the Society’s key objectives. As such, we were keen to restore our Reading Room service as soon we possibly could. Providing access to our collections, however, had to be balanced against our responsibility to minimize risk to our users and staff. In order to maintain social distancing in our Reading Room and elsewhere in the building, we will initially limit reader numbers to three per day, by appointment only. Appointments will be allocated on a first-come, first-served basis. To make an appointment, please email the Librarian, Edward Weech, at ew(at)royalasiaticsociety(dot)org.

Readers must tell us what they would like to see when making their appointment. If you do not know exactly what you need, we can try to help you identify the right materials before your visit. It may not be possible to retrieve additional material after you have arrived and in order to allow as many people as possible to use our services, we will be limiting people to one appointment each for the time being.

For full details of how to access the collections please read this statement on our website.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

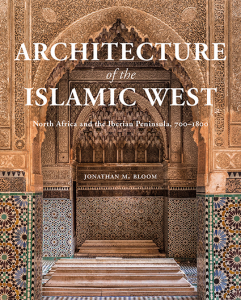

On Wednesday 1 July we were delighted to host the Zoom launch of Professor Jonathan Bloom’s new book, Architecture of the Islamic West: North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula 700-1800. Over 100 people from around the world were able to enjoy Professor Bloom’s slides of the many places he has visited in researching for the book and the tales he had to tell of his trips. He presented a survey of the book’s contents which was followed by a lively question and answer session. Despite the time differences we had participants from the USA (Professor Bloom, included) to China – one of the advantages of using an online forum. Copies of the book are available from Yale University Press.

We hope that this will be first of many such events as we head into our Lecture programme in the autumn. Our Director, Alison Ohta, is currently arranging our 2020-2021 Lecture Series which will include both online and ‘on-premises’ events.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Here is more news from the Journal:

Regular issues of the Journal are possibly more special and less ordinary than their description implies. Last week’s blog post highlighted how JRAS stand-alone articles have a very crucial role to play in the Journal’s activity. As well as contributing to key debates, they can often tackle less familiar questions and in so doing allow readers to engage with topics that may become the ‘mainstreams’ of the future. Below two authors, whose research findings appear in our most recent issue, explain how they became interested in the subjects of their recently published articles.

Sergey Minov, author of Friday Veneration among Syriac Christians: The Witness of the Story of the Holy Friday writes about his article:

I am fascinated by Syriac hagiographical texts from Late Antiquity and Middle Ages as a repository of otherwise forgotten or marginalised traditions and ideas, as in the case of the text, published in my article, which promotes an unusual, for the mainstream Christian tradition, way of venerating Friday, i.e. by complete abstaining from work on this day.” Click here to gain access to Sergey’s article.

Gagan Sood, author of Knowledge of the Art of Governance: The Mughal and Ottoman Empires in the Early Seventeenth Century writes about his article:

Are there are any South Asians in South Asia? Are there any Middle Easterners in the Middle East? The short answer is no. This is because few, if any, of the region’s inhabitants think of themselves as such. And yet these are the kind of geographies which continue to dominate our mental maps today. Many scholars have shown that current notions of a Middle East or of a South Asia are recent constructs, a century old at best. These constructs perhaps reflect, and reinforce, the geopolitical dynamics of their provenance, conceived and elaborated at various points between European colonialism and the Cold War.

My research gradually turned into a project to recapture through vernacular sources the world of ordinary but literate people living in the region in the mid-eighteenth century, who were engaged in activities, such as trade, pilgrimage and scholarship, typically marked by large distances and long silences. I found that the geography which framed their world stretched across much of India and the Islamic heartlands – al-Hind and al-Mashriq – from Sarajevo to Hyderabad, from Tihama to Crimea. That was an unexpected finding. It spurred me to carry out yet more research into the matter. This has crystallised in the form of a second project.

The new project investigates the realities of governance under the Mughal and Ottoman empires over the seventeenth century. As part of it, I am interested in the shared world of the region’s ruling elites at the time. An important source for accessing this shared world are advice-to-kings treatises. A number of these are known to exist for the Ottoman Empire, and have long been studied by scholars. In seeking additional sources for the project, I chanced across an advice-to-kings treatise for the Mughal empire, by the noted thinker ʿAbd al-Ḥaqq Dihlavī. Now that made me sit up and pay attention because the Mughals, unlike the Ottomans, are not supposed to have had a tradition of high-level policy debate. Well, as proved by this treatise they did, at least more so than has been commonly thought by specialists to date.

To try and make the most of ʿAbd al-Ḥaqq Dihlavī’s treatise, I chose to analyse it in juxtaposition with the most comparable Ottoman treatise, by the courtier and government official Koçi Bey. This in turn required me to fashion a novel approach suited to the sources and their historical context. The result of that analysis is a host of findings which shed fresh light on the heuristics of sovereign governance in the Mughal and Ottoman empires in the early seventeenth century. By extension, they provide further evidence for the existence of a regional world of significance not just for its inhabitants but also for broader developments linked to the genesis of the modern world.

Click here to gain access to Gagan Sood’s article. And for more information about the Journal you can always visit our website.