Language and Culinary Culture – Dinner Menu for International Congress of Orientalists

Some time ago, a researcher visited us to consult the papers of the International Congress of Orientalists held in our collections. Although these papers are classified as part of our institutional archives, they are external to the Society – meaning they were not produced through the Society’s own activities, but rather stem from our interactions with other learned societies and our engagement in the broader academic world.

The International Congress of Orientalists was founded in Paris in 1873 as a forum for scholars and delegates from around the globe to meet, present research and exchange ideas in the field of Asian Studies. The Congress was organised into various sessions, each focused on a specific Asian region and covering disciplines such as history, language, archaeology and more. Over its long history, the Congress convened at intervals and was hosted by different countries, with early editions predominantly held in Europe.

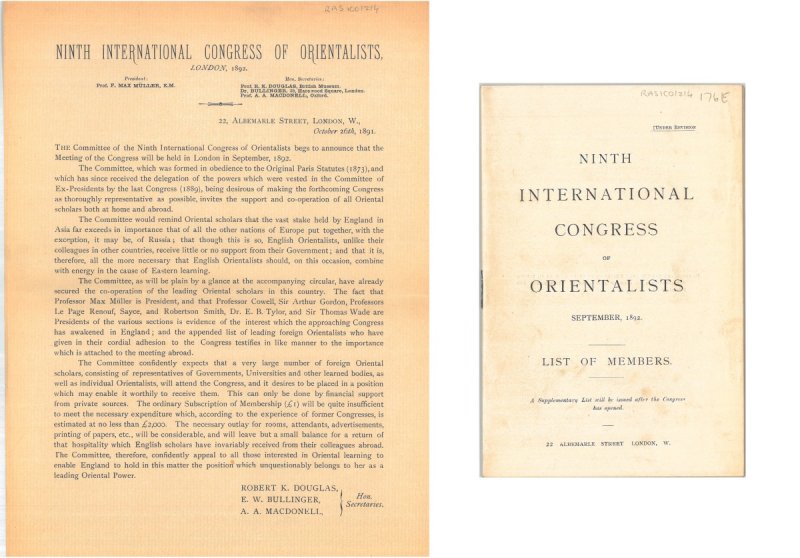

From the surviving papers in our Archives it appears that the Society was an active supporter, and a direct participant in many cases, of the early editions of the Congress. Indeed, we know that Sir Henry Creswicke Rawlinson chaired the Semitic Section for the first edition of conference as President. But the records for the Congress in our Archives only begin with the 8th edition, held in Stockholm and Christiania (now Oslo) in 1889, and cover until the 34th edition in Hong Kong in 1993. These materials include pamphlets, meeting minutes, session proceedings and related correspondence, amounting to one box of archival material. The collection is catalogued in our Archive catalogue here.

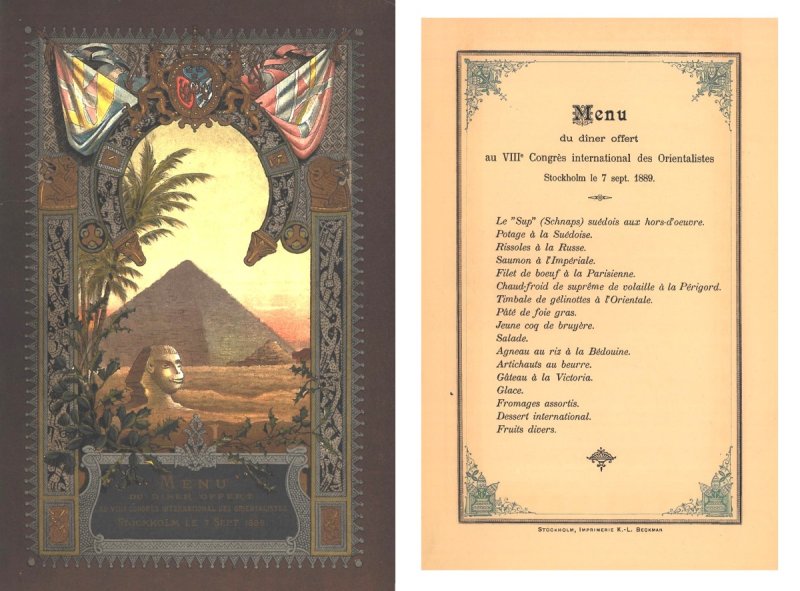

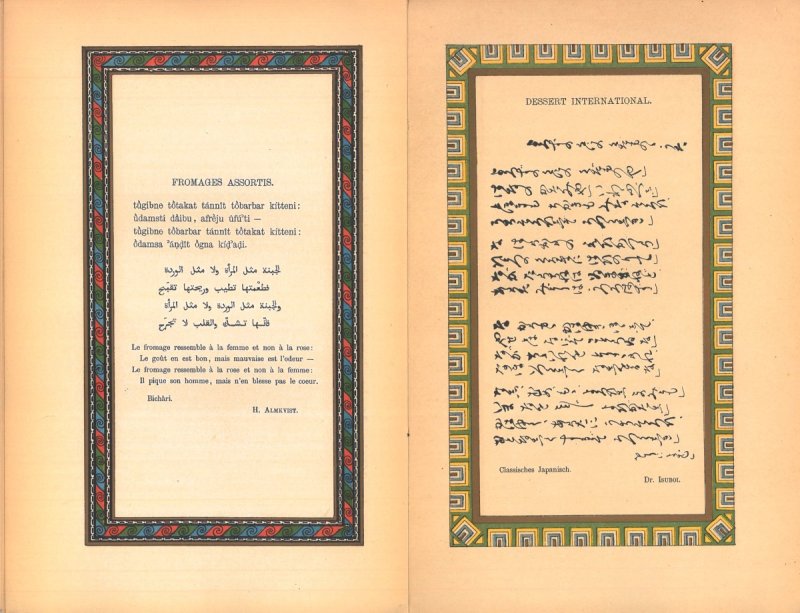

The item that caught my attention – which also prompted this blog post – is a dinner menu booklet from the 1889 Congress. Its cover design pays homage to one of the world’s oldest civilisations, featuring a pyramid and what appears to be an Egyptian sphinx, framed by decorative borders and crowned with the coat of arms of the Kingdom of Sweden and Norway. Inside, an insert lists the courses served at the dinner, and the main body – nearly 50 pages long – is a fascinating interplay of language and culinary culture. Each dish is celebrated by a poem or passage written in an Asian language, followed by a translation in either French, German or English – the designated lingua francas of the Congress.

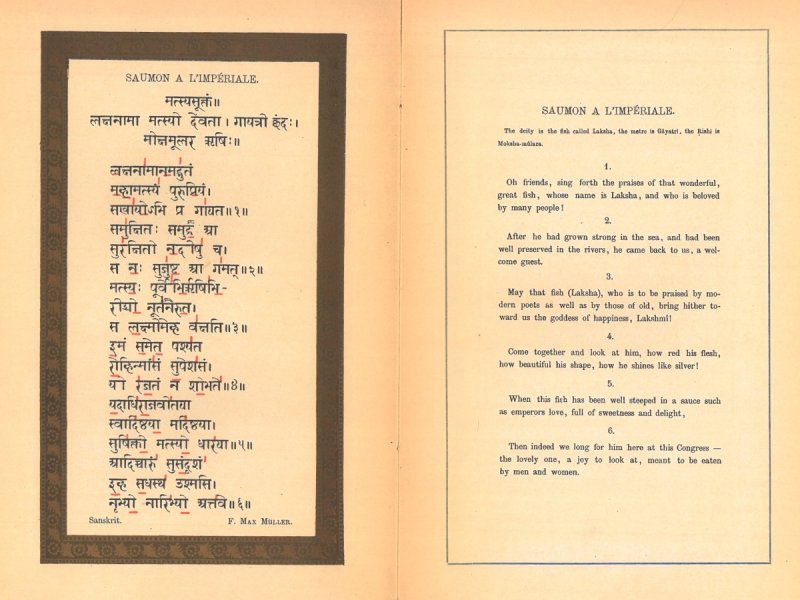

The languages featured span both ancient and modern, including Hieroglyphs, Cuneiform, Hebrew, Manchu, Malay, Javanese and many others. One dish, called ‘Imperial Salmon’, is celebrated with a Sanskrit poem signed by F. Max Müller, German-British philologist who studied Sanskrit among other languages. The poem contains references to Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth and prosperity in Hinduism, and its English translation is as follows:

Oh friends, sing forth the praises of that wonderful, great fish, whose name is Laksha, and who is beloved by many people!

After he had grown strong in the sea, and had been well preserved in the rivers, he came back to us, a welcome guest.

May that fish (Laksha), who is to be praised by modern poets as well as by those of old, bring hither toward us the goddess of happiness, Lakshmi!

Come together and look at him, how red his flesh, how beautiful his shape, how he shines liver silver!

When the fish has been well steeped in a sauce such as emperors love, full of sweetness and delight,

Then indeed we long for him here at the Congress — the lovely one, a joy to look at, meant to be eaten by men and women.

Another standout for me is a Chinese poem dedicated to the dish ‘Swedish Soup’, written in the classical seven-character verse form. It references several legendary cooks and their culinary achievements throughout Chinese history, concluding with the bold claim that none of their delicacies compare to the Swedish soup – what a praise! Sadly, the menu offers no details about the soup’s ingredients or preparation, leaving me wondering how impeccable its taste must have been.

The range of the languages featured in the menu is so wide, so it is understandable that whoever was putting together the booklet could not have mastered them all. Those who are familiar with the Japanese language, for example, could probably spot a printing error on the page for ‘International Dessert’ – the classical Japanese text is printed horizontally, when the text is supposed to be read vertically from right to left.

This menu offers a delightful glimpse into the diversity and beauty of Asian languages, presented in a convivial setting that contrasts with the more formal and scholarly tone of the Congress itself. It, in a way, also speaks to the Congress’s international character and the expansive scope of its subject matter. Due to the Congress’s unique setting and global reach, researchers have examined how early editions of the Congress can shed light on East-West dynamics and relations. How did scholars conduct and communicate research in Asian Studies? How were Asian history and cultures represented at the Congress? Was that representation accurate and respectful?

These are important questions that merit further exploration. But in my view, they don’t diminish the charm of the menu. So, I hope this short blog post has given you some food for thoughts (pun intended), and if you are intrigued by how Victoria Sponge and Foie gras were celebrated with creativity more than a century ago – do get in touch!

James Liu