Grand-nephew of Napoléon I, Prince Roland Bonaparte (1858-1924) took a gentleman’s interest in the natural sciences. Between 1882-1889 he produced a photographic study of different ethnic groups, described as an ‘anthropological collection of human diversity’.

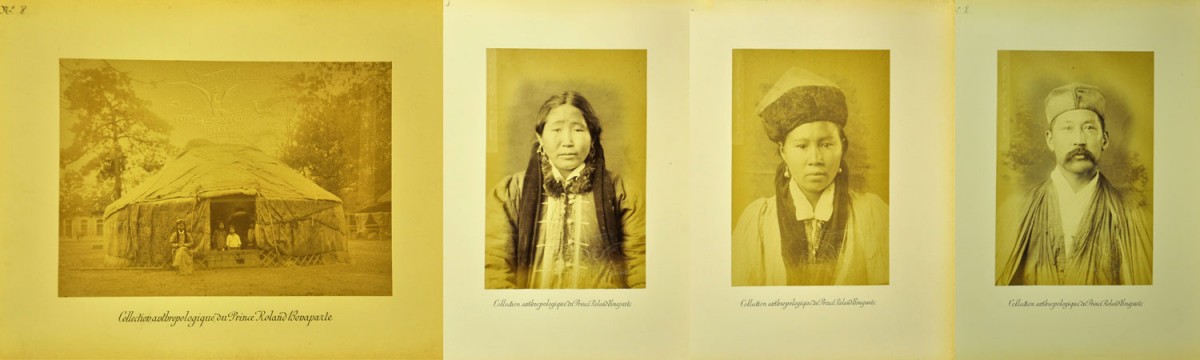

The collection consists of 165 albumen prints mounted on pasteboards and stored in portfolios organized by ethnicity, including ‘Hindous,’ ‘Atchinois’, ‘Dahoméens’, ‘Hottentots’, ‘Bushmen’, ‘Néo Calédoniens’, ‘Australiens’ and ‘Peaux Rouges’.

As was common during the period, Bonaparte used photography as a scientific tool for collecting data. Having received training from Paul Broca, his work reflects the anthropology of the time, which focused on the documentation of physical characteristics as a means of establishing relations between the human races. Accordingly, the subjects are represented in full-face and profile torso portraits, and frontal, profile and back full-length portraits. Group photographs and views of typical dwellings are also included.

The Royal Asiatic Society houses one such portfolio in its Photographic Collection. Donated by Prince Bonaparte in 1883, the portfolio contains studies of the Kalmyk people.

The ancestors of the Kalmyks, the Oirats, were a group of the Mongols who migrated from the steppes of southern Siberia to the Lower Volga region. Today, the Republic of Kalmykia is a federal subject of Russia and is the only region in Europe where Buddhism is practiced by the majority of the population.

It is unlikely, however, that Bonaparte travelled to Russia have these photographs taken. In late-nineteenth century Europe, it was not considered degrading or racist to exhibit humans in ethnographic displays. The 1883 Colonial Exposition in Amsterdam, for example, featured a reconstructed Javanese-style settlement with ‘natives’. A major attraction of the 1889 Paris World’s Fair was a ‘village’ containing 400 indigenous people whose native counties had been colonised by Europe. The majority of Bonaparte’s portraits were taken at temporary exhibitions such as these.

A document accompanying Bonaparte’s study of the Kalmyk people suggests that the photographs were taken at the Jardin Zoologique d’Acclimatation in Paris. Established in 1860 by a society dedicated to the study of animals and plants for the benefit of France and its colonies, towards the end of the century the Jardin also featured temporary ethnographic displays. These highly popular exhibits situated ethnic groups in surroundings designed to resemble their native environments. In 1883, the year that Bonaparte donated the portfolio housed by the RAS, the Jardin staged a display of Native Americans and Kalmyks.

Closed in the early twentieth-century, the site of the Jardin d’Acclimation is now a children’s amusement park. Today, the Collection Anthropologique du Prince Roland Bonaparte: Kalmouks serves as an important document of Europe’s colonial history.

To locate this collection on our Library catalogue, search for Photo.49. This collection of photographs has also been digitised and can be viewed in our Digital Library here.

Bibliography

EAP207/4: Collection anthropologique du Prince Roland Bonaparte [c 1883 – 1889], Endangered Archives, British Library (2016) http://eap.bl.uk/database/overview_item.a4d?catId=142094;r=12316 [accessed 15 June 2016]

Gindhart, Maria, ‘Ethnographic Exoticism: Charles-Arthur Bourgeois’s Snake Charmer’, Material Culture Review, No. 79 (Spring 2014), pp.7-24.