Commemorating John Drew Bate

This Sunday, 26 January, marks the 102nd anniversary of the death of the missionary John Drew Bate. He died on the 26th January 1923. In the 1923 Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, George A. Grierson paid tribute to Bate:

‘The Rev. John Drew Bate was born in Plymouth in the year 1836, and by his death at a ripe old age the Society has lost one of its oldest and valued members. He was sent to India by the Baptist Missionary Society in 1886, and after a short stay in Western Bengal, was posted to Allahabad (now Prayagraj), where, earning the respect and affection of all classes of the community, he laboured for nearly thirty years before his retirement in 1897. He became a member of the Asiatic Society of Bengal (now Asiatic Society, Kolkata – see last week’s blog) in 1873 and of this Society in 1881. This is not the place for describing his evangelistic work as a missionary, but a tribute must be paid in the pages of our Journal to his great knowledge of the people amongst whom he lived and of their language. With the latter he acquired an intimate familiarity, ripened by a sympathetic scholarship, and by his share in the translation of the Scriptures and by his other linguistic work he successfully carried on the tradition of learning which had been founded by his great predecessors in the same Missionary Society, Carey, Ward, and Marshman.

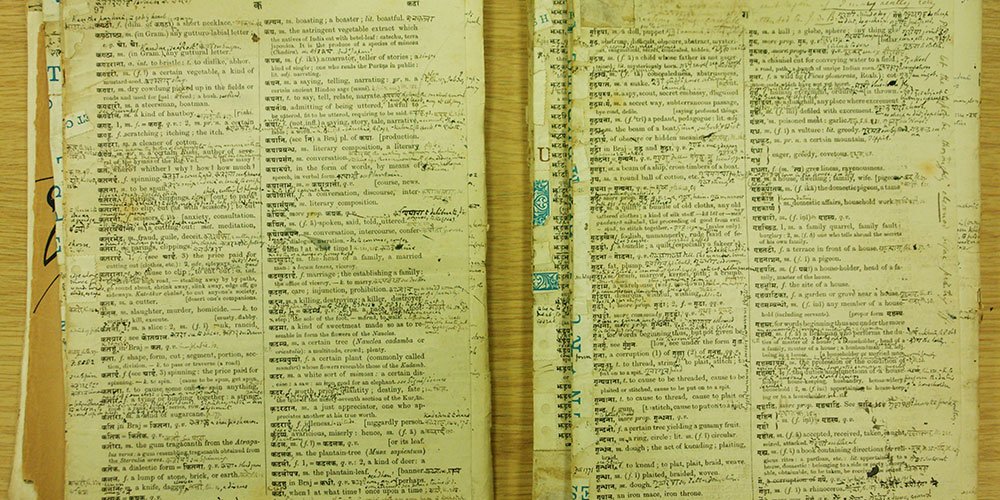

‘He is best known to Orientalists as the author of the Hindi Dictionary published in 1875, which is still the standard work on the language (as of 1923) and has lately passed through a second edition. Some idea of the extent of his researches in connexion with this valuable work may be gathered from the fact that through his reading alone he was able to add no fewer than twenty-five thousand new words and forms of words that had not hitherto been explained. In regard to the width of his attainments, which were by no means confined to the language of the dictionary of which made him famous, I take the liberty of quoting the remarks of a most competent scholar who sat at his feet in Allahabad and who knew him well. In the Missionary Herald for March, 1923, the Rev, G.J. Dann writes:-

“His knowledge of the classical as well as the vernacular literature of India was great especially of Muhammedanism (Islam), in which his learning was encyclopaedic. Only one of the many volumes he wrote on this subject – Studies in Islam – was ever published…”

‘His later years were clouded by ill-health, which prevented him from taking an active part in our proceedings, and he passed peacefully away on the 26th January of this year. The only son who lived to man’s estate became one of the sacrifices of the war, and every member of the Society – especially those whose lot was cast in northern India – will extend their liveliest sympathy to his widow and her daughters in their latest bereavement.’

Though this obituary is couched in the language of its time, it reveals a man dedicated to learning and facilitating others in their research and knowledge. It is hard for us, with Google and the growing use of AI, to imagine one man painstakingly working through the literature of an area to create a dictionary from scratch. This dictionary, after publication, was subsequently used in Hindi-speaking schools in India.

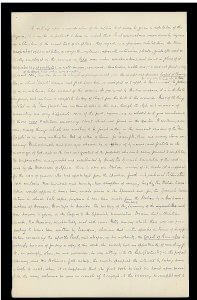

As I have written before, the Papers of John Drew Bate were the first set of papers I catalogued at the Society, back in 2015. When I wrote that previous post, in 2024, I was in the process of creating our bespoke archive catalogue to which I was transferring the completed 250 catalogues. A year on, the catalogue is up and running and researchers can now access 290 catalogues. These range from single items to complex sets of personal papers, special collections and institutional records, and represent a significant percentage of the Society’s archival holdings. Currently two more catalogues are in preparation and hopefully will be added in the next few weeks. I am working on the institutional collections records specifically those that represent engagement with the collections in a variety of ways including research-led information, articles, correspondence giving further information about our collections, and a bound volume listing the names of people who visited the Society’s museum between 1832-1840. The early correspondence includes a letter from Michael Faraday, at the Royal Institution, concerning the constitution of a bowl from Java which was made from an alloy of copper and tin.

One of our volunteers, meanwhile, is working on the Papers of Reginald Campbell Thompson, an archaeologist. This is a very new acquisition of notebooks from his early career which is a welcome edition to his glass slides in the collection and the film of his Excavations in Iraq.