An Ode to Ordinary People – Imperially Commissioned Illustrations of Tilling and Weaving

Every now and then I enjoy opening a random box on the shelf and get my teeth into something that is yet to be processed. Last week, as I was cataloguing some prints and drawings (more information in a previous blog post here), I found an item annotated ‘Chinese concertina book on rice and silk production) in a box labelled ‘Uncatalogued Drawings’, which immediately piqued my interest.

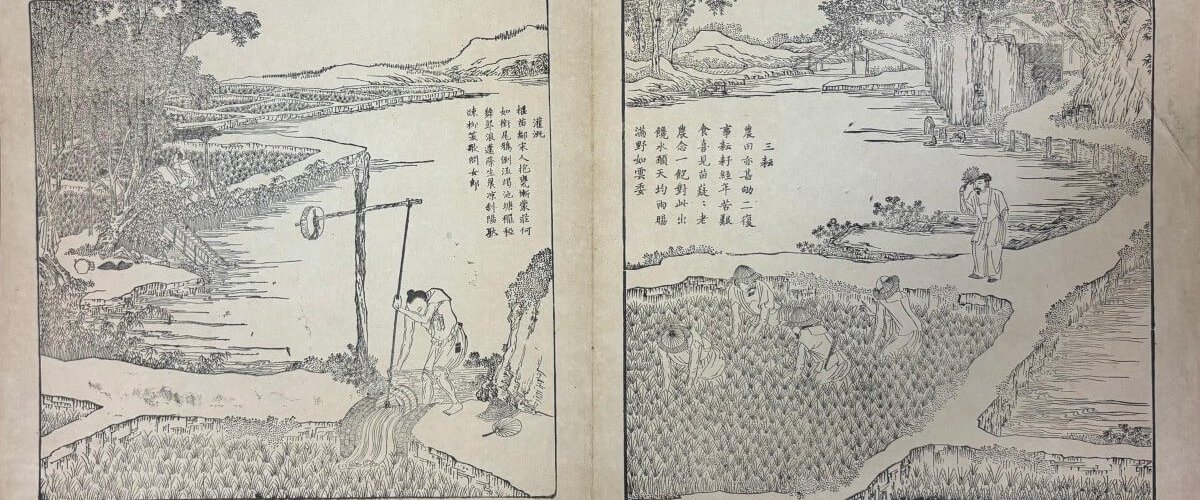

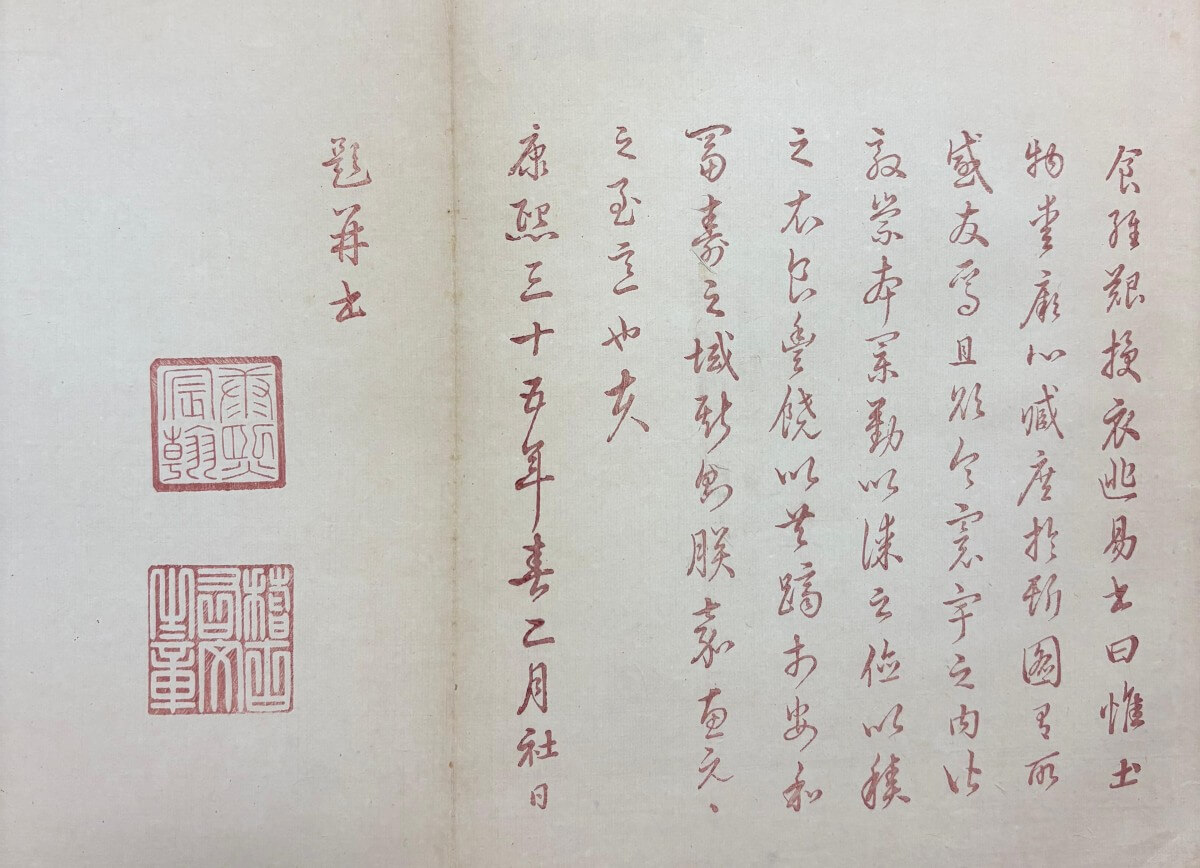

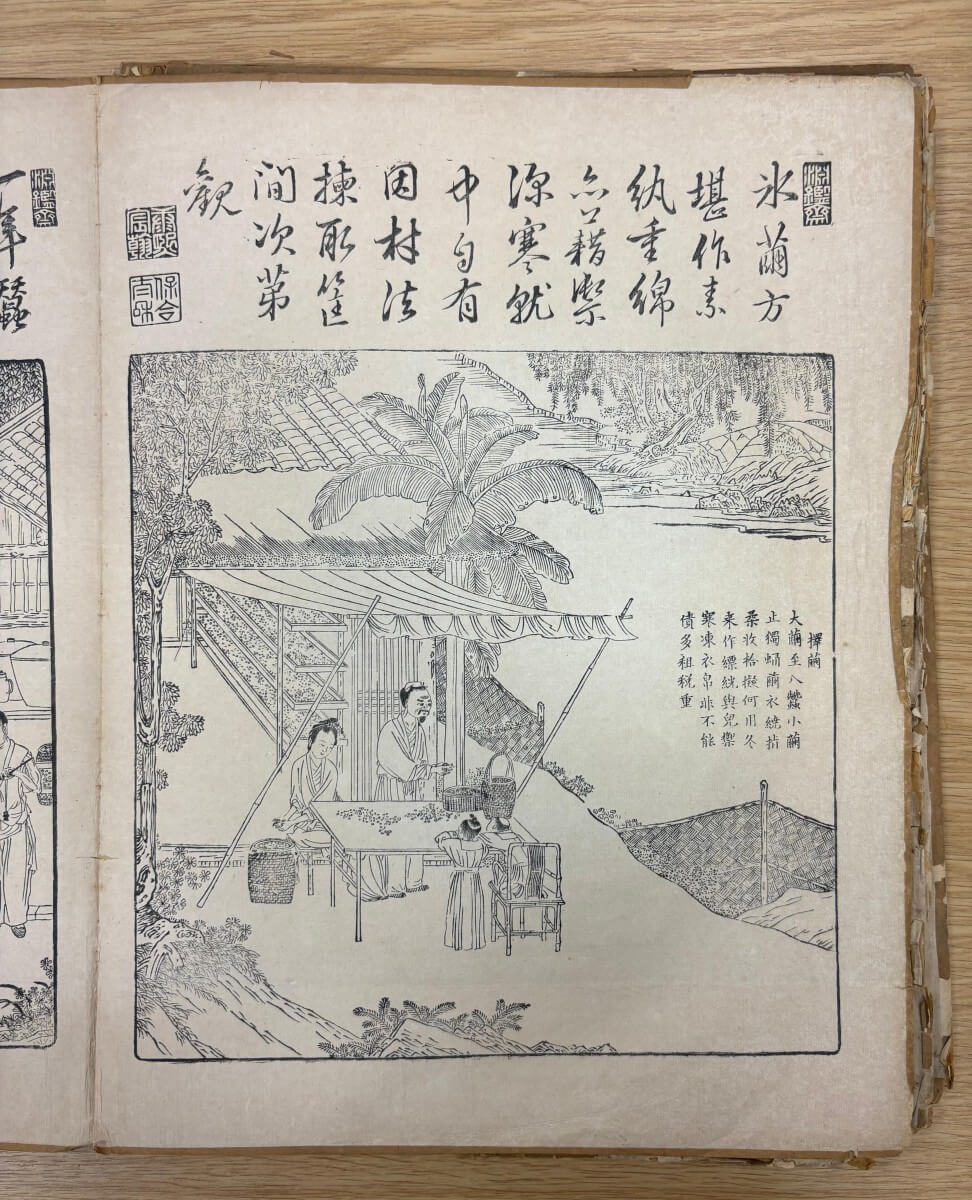

The book contains multiple woodblock-printed illustrations depicting the processes of rice growing and silk production, each accompanied by Chinese calligraphy in the upper margin. There is also a preface with text in Chinese calligraphy. The calligraphy is not immediately discernible to the untrained eye (like mine), but – based on my knowledge in the Chinese language – I was able to make out certain words in the preface, including the dating which reads ‘康熙三十五年春二月社日’. This dates the book to February of the 35th year of Emperor Kangxi’s reign of the Qing dynasty, i.e. 1696 in the Western calendar. This, combined with the subject information, was sufficient for me to conduct a desktop search about the book.

It turns out that the book is a copy of the first edition of Imperially Commissioned Illustrations of Tilling and Weaving, or ‘Yu zhi geng zhi tu 御製耕織圖’, which was printed in 1696 by order of Kangxi. These illustrations were first created in the Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279) in China, a period when particular emphasis was placed on agricultural development, resulting in a tremendous increase in productivity in rice farming, silk weaving, tea production and other trade. Since the book’s first publication, later emperors had recognised its significance as an important visual representation of agricultural practice, and multiple editions of the book were commissioned in the Yuan, Ming and Qing dynasties. In the preface of this 1696 edition, Kangxi writes that he sees food and clothing as the fundamental needs of people, and orders the book be printed to celebrate the hard work of farmers and weavers.

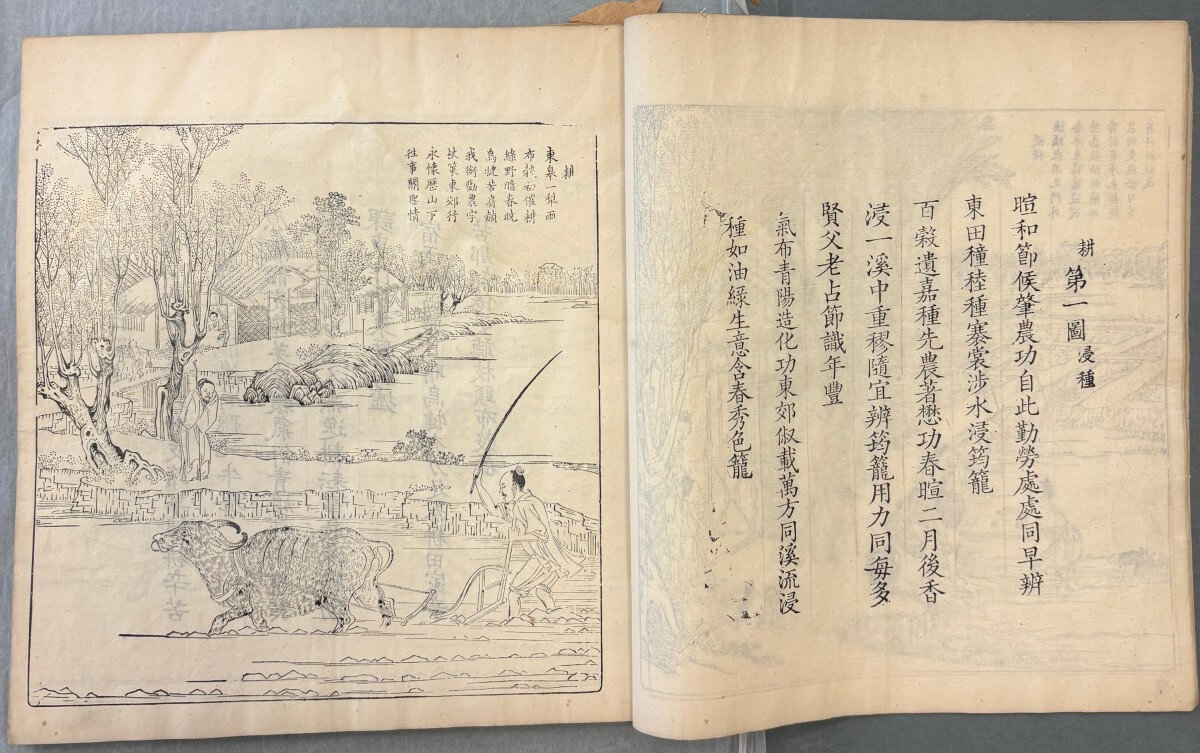

The illustrations are indeed delightful to see. Each print contains an explanatory passage, and is accompanied by poetry composed by Kangxi. They illustrate the tools, conditions and skills required in each step of the production process with fine detail. The book also strikes me as an ode to ordinary people – a testimonial of the laborious efforts that go into the production of a thread of silk and a grain of rice, which warrant respect and appreciation. Upon comparing our copy with other copies held at other institutions, I found that the first part of the preface, where the title of the book would have been written, has unfortunately gone missing. The book has also disintegrated into several sections with crumbling edges, but the prints themselves are in a reasonably good condition and are safe for consultation.

But the story does not end here. After researching for the book, the next day, in a Miscellaneous Manuscripts box, I stumbled upon another item labelled ‘Chinese book on riziculture and sericulture’. Sounds familiar, right? As I opened the package I found not a manuscript, but another copy of Imperially Commissioned Illustrations of Tilling and Weaving!

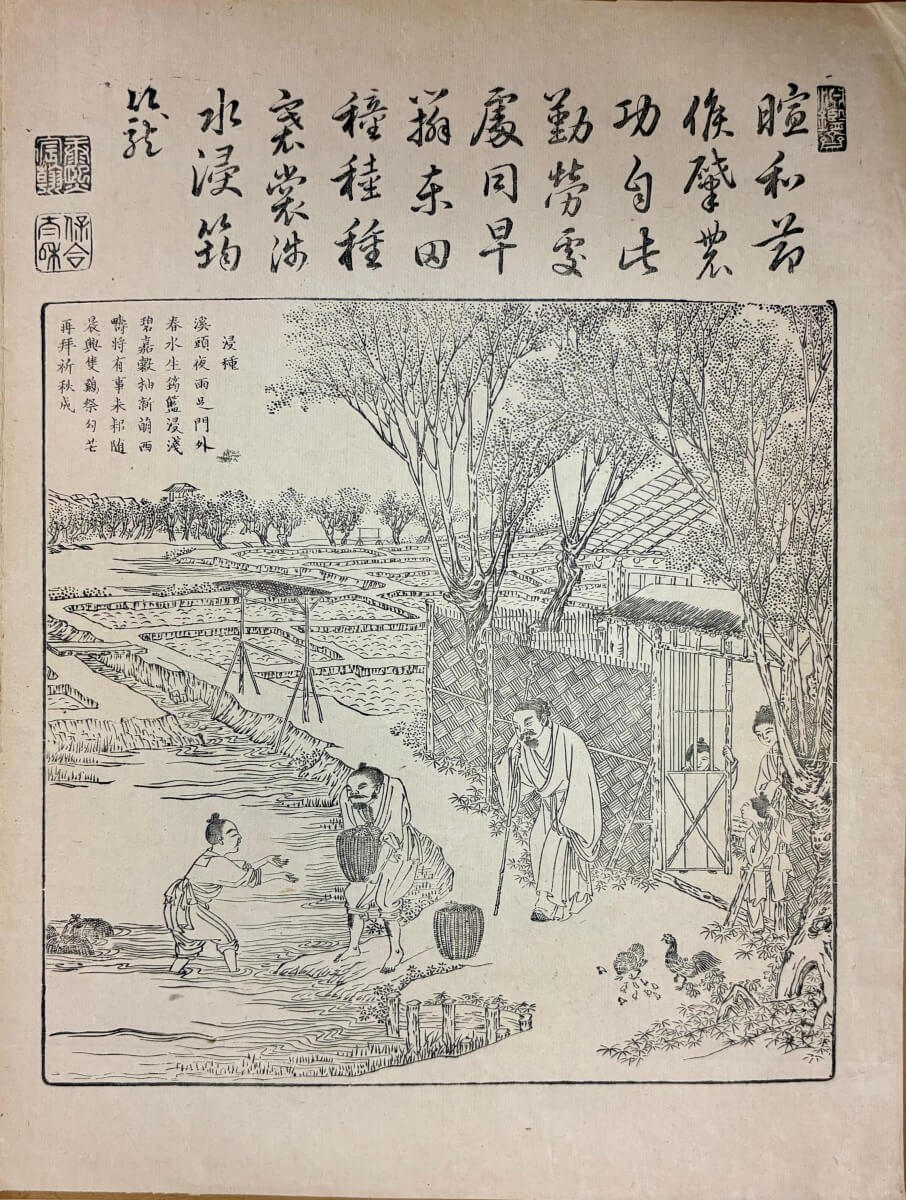

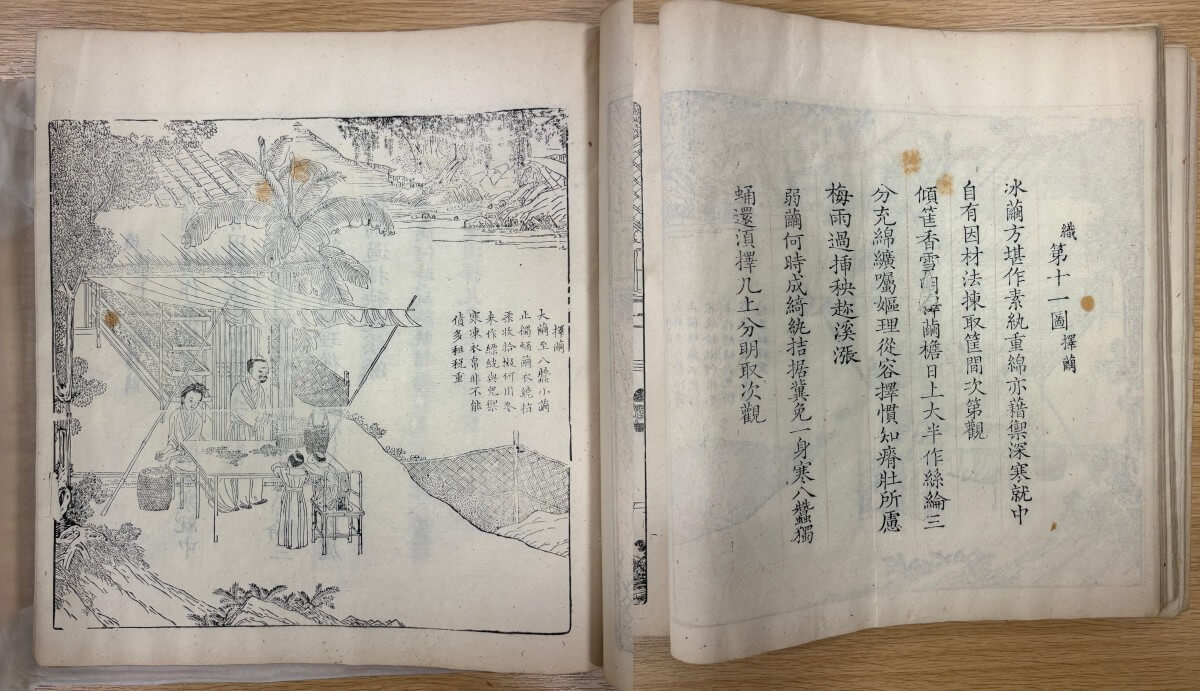

Although containing identical woodblock-printed illustrations, this second copy is in a very different format than the first one. It is longer in height but slightly shorter in width, and is in traditional thread binding. It has the same 1696 dating in its preface, which is complete but has almost lost all of its colour. The biggest difference between the two copies lies in their text: each illustration in the second copy is followed by a full page of text, which is also poetry, opening with the numbered title of the print.

Upon closer examination, I found that each passage starts with the same poetry composed by Kangxi, but is followed by additional poetry composed by his successors, emperors Yungzheng and Qianlong, the latter in honour of the original poetry by Kangxi. Both Yungzheng and Qianlong ordered reprints of the Imperially Commissioned Illustrations of Tilling and Weaving, and although no major alterations seem to have been made to the illustrations, they penned new poetry to complement the visuals. The inclusion of additional poetry in this copy suggests that it is a later edition and, therefore, is datable to the reign of Qianlong in the 18th century.

The Imperially Commissioned Illustrations of Tilling and Weaving has been widely cherished for its imperial connection and cultural significance. Multiple copies of different editions, in different formats, composition, binding and decorative styles, have survived in institutions worldwide. The British Museum, for example, holds a similar – but coloured – version to our first copy (images here), while the Library of Congress of the US has a highly decorated copy on silk in similar composition to our second copy (images here). These are all valuable sources for studying how this important title was used and perceived. I am pleased to learn that the Society’s collection contains two copies of different editions of this book and, although more humble in terms of binding and decorative styles, they are no less worthy in reflecting its enduring legacy.

So, the two copies have now been catalogued under Special Collections in our Archive catalogue, and their entry can be found here. If you are interested in finding out more about the book, The Artful Fabric of Collecting website hosted by the University of Oregon Libraries has an excellent overview of its history and evolvement, which I benefited from in my research process (link here).

James Liu