A Voyage to the Southern Seas

This week I went to the “James Cook: The Voyages” Exhibition at the British Library – in fact it was a family affair as I met up with my two sisters and we visited the exhibition together. It is a bit late for me to recommend it, though I do, as the exhibition closes on the 28th August. But if you have some time over the Bank Holiday Weekend and are in London, then you could avail yourself of the “bounty” of the exhibition. I learnt a lot about the voyages that Cook undertook, and something about their consequences in our global history. And I was intrigued to learn a little bit more. That is when it is advantageous to be working in a place such as the Royal Asiatic Society with its many Collections. So, although, the Southern Seas cannot be classified as Asia, I did find in our Collectioons, “A Missionary Voyage to the Southern Pacific Ocean performed in the Years 1796, 1797, 1798…”

The book was rebound in 1928 funded by a Carnegie U.K. Trust Grant, and therefore not with its original 1799 binding; it does still contain all the original text and plates, which reveal much of the journey and the purpose for it.

I am not going to enter into the discussion concerning the rights and wrongs of missionary ventures or European colonisation. Despite some of the devastating consequences, what still impresses me about some of these men and women was their willingness to travel into the almost unknown, with considerable risk that they would not return, and if they did, their great desire to share the knowledge they had gleaned, however imperfect we may deem it now. This book, according to its “Advertisement” was put together in great haste: “The impatience of our brethren to gratify the curiosity of the public, must plead our excuse that the following are arranged in a less lucid order than we could have wished. In collecting from the public and private journals, we have desired to preserve the language of the relator, which, if not the most polished, may not-withstanding be the most affecting.”

The ship they travelled on was called the Duff under the command of Captain James Wilson. There were 22 crew members including the captain. The list of missionaries included 4 ordained ministers, but then a further twenty-six men including a hatter. a weaver, a bricklayer, cabinet-maker, shoemaker and surgeon. There were also 6 women in the group, and 3 children, the wives and family of some of the men. They left Woolwich on 10 August 1796 but then got held up at Portsmouth waiting for the East India fleet with which they were going to sail. They finally set sail on their mission on 24th September, arriving at the port of Rio de Janeiro in November.

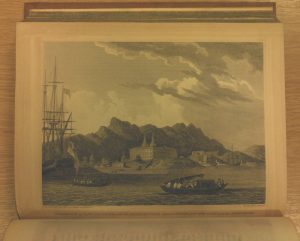

William Wilson was the first mate on the ship, and nephew of the Captain. He was obviously also a competent artist, providing sketches for all the plates in the book. The missionaries were shown around Rio de Janeiro: “The streets were full of shops of every kind: the druggists and the silversmiths’ made the noblest appearance. We observed a large reservoir of water, with three fountains discharging into it, very sweet and convenient for the shipping…”

They left Rio de Janeiro, travelling round Cape Horn, and hit bad weather which weakened both crew and passengers. Therefore the captain decided to travel via the “Eastern passage” On the 1st January 1797 it was recorded, “We have now sailed twelve thousand miles” and on 21st February, “Ninety-seven days had now passed since we left Rio de Janeiro, and except one vessel which we met with a week after our departure, we had not in all this time seen either ship or shore, and had sailed, by our log, thirteen thousand eight hundred and twenty miles, a greater distance probably than was ever before run without touching at any place for refreshment, or seeing land.”

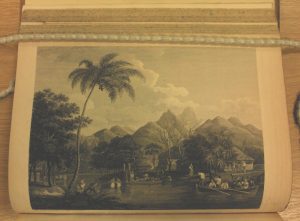

But that day, they saw “Toobouai” (Tubuai or Tupua’i ). The captain did not intend to go near the island, “he thought it not prudent to land on account of the natives being prejudiced against the English through the mutineers of the ship Bounty, who had destroyed near a hundred of them.” But they sailed near enough for the passengers to feast on the sight of land and headed for “Otaheite” (Tahiti). The missionaries, during their journey had prayed and deliberated upon which islands they wished to disembark, and lists were drawn up for Otaheite, Tonga Taboo (Tongatabu, Tasmania), and Santa Christina. Having left the waters near Tubuai, they again hit bad weather but finally reached Tahiti on 5 March 1797.

Some settled in Tahiti, and records of their early conversation with the island people are included. The ship sailed on to the Friendly Isles (Tonga). None of the ordained ministers had chosen to remain here so Seth Kelso (weaver) and John Harris (cooper) were ordained for the task.

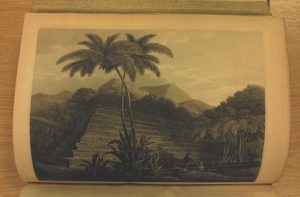

They made a short trip to the island of “Eimeo” before setting sail for “Tongataboo”, where several more of the missionaries were left.

On 23rd May, they spotted land, previously unknown. The wind was light so they failed to reach it before nightfall. The next morning, “we hove the ship to, and putting two seamen in the jolly-boat, Mr Wm. Wilson and Mr Falconer, with Peter and Otaheitean Tom…rowed towards the shore, intending to land if the natives ere friendly…But on our approach they collected themselves in a body to oppose our landing. As they walked along the shore, the women followed with spears…”A decision was made not to land but the island was named “Crescent island, on account of its form; it is six of seven miles in circumference, and lies in lat. 23º 22’S. long. 225º 30’E.” This first discovery was followed by finding several more islands which were grouped together and named Gambier’s Islands, “in compliment to the worthy admiral of that name, who, in his department, countenanced our equipment”.

They sailed on to the Marquesas Islands were two more missionaries were left before the ship returned to Tahiti where further exploration and interaction with the island people took place.

Exploration around the South Sea Islands continued until September 1797 when the Duff began its voyage towards China, stopping at the “Pelew Islands” in November, arriving at the “Macao road” on 20th November. They needed a chop to gain permission to travel further so Captain Wilson went ahead in the Britannia to try to gain the necessary permissions. There they were to pick up a cargo to return to England. By 31st December they were fully-laden and joined others to begin the journey home. taking until the 11th July the following year, to anchor in the Thames. An epic voyage in which: “We have not lost a single individual in all our extended voyage: we hardly ever had a sick list: we landed every missionary in perfect health: and every seaman returned to England as well as n the day he embarked at Blackwell.” If that is to be believed, that was an incredible achievement. The book runs to 420 pages, so I have only been able to touch on a brief amount of the information contained within it. However anyone is welcome to come and view it within our Reading Room, and learn more about this venture.