Cristeena Chitrakar: Nepal Remembered (guest blog)

This week we were delighted to host a photo exhibition and talk, followed by book signing of Nepal Remembered with author Cristeena Chitrakar.

For those unable to join us on the night, the full talk can be viewed on our YouTube channel:

Cristeena also kindly agreed to write a guest post for the blog, which we hope you enjoy!

My last name Chitrakar translates to painter and I come from a family of artists. Growing up I was always asked if I would follow my ancestors footsteps as painters and photographers. However, I was more captivated by the stories behind the images. I am surrounded in my house by photographs – but they are pictures of people who were not my relatives, palaces that were not my family home, and images of culture and landscape that were changing before my eyes. I wanted to share these stories and to capture them in a way that honored my family’s legacy and what better way to record this than through a book.

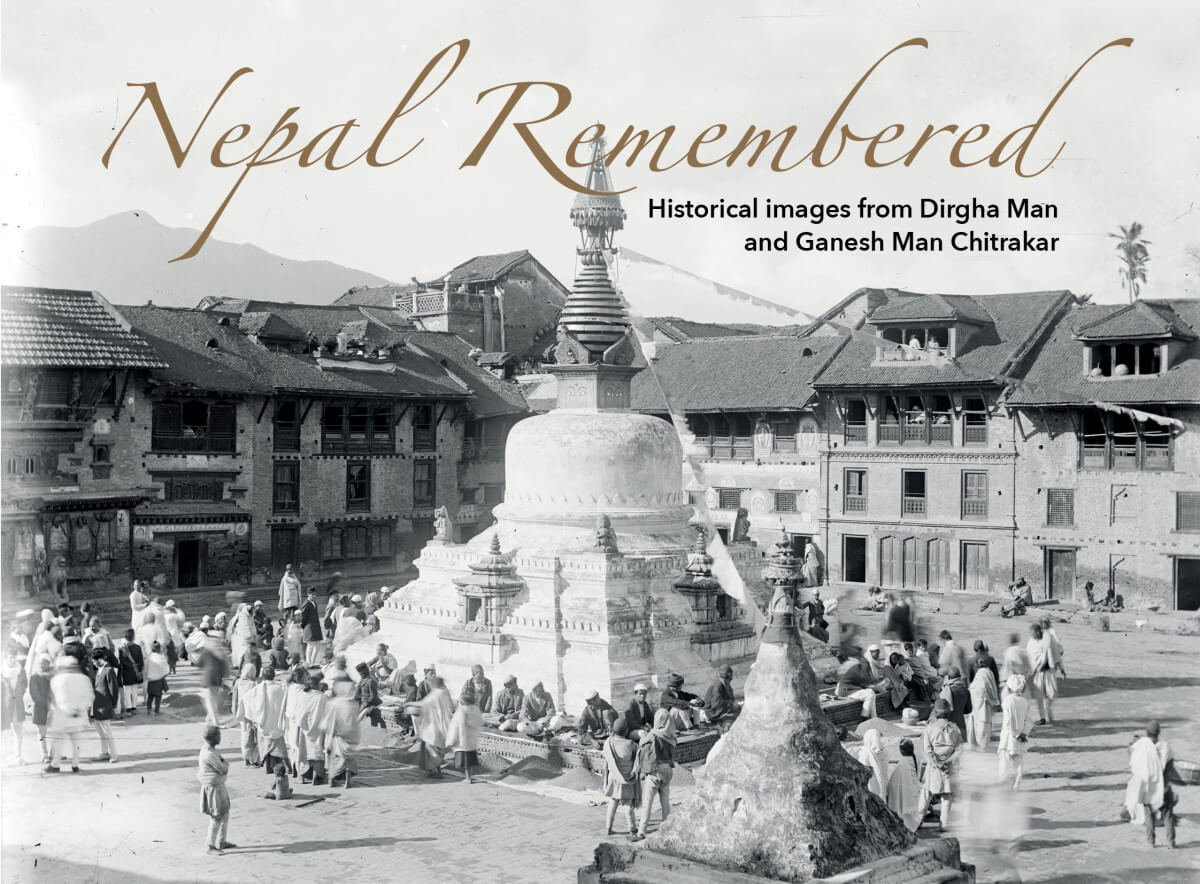

Nepal Remembered: Historical images from Dirgha Man and Ganesh Man Chitrakar is the result of their achievements. It illustrates the dialogue between the photographer and his subject and captures an era that has already gone, revealed in the photographs. Dirgha Man, my great grandfather, was known to be a very talented painter. When Prime Minister Chandra Shamsher happened to notice a medallion painted by him, he immediately hired him. When photography was introduced to Nepal in the late 1800s, Dirgha Man added it to his visual repertoire. Photography was the preferred medium as it was easier and faster to capture than paintings. He accompanied Prime Minister Chandra Shamsher in his entourage to England in 1908. From there he brought a camera which he used for the majority of his life in the palace documenting Prime Minister Chandra Shamsher and subsequent Prime Ministers, their achievements, families, ceremonies and palaces. Photography was accessible to the privileged few and besides documenting the Rana pomp and glamour, the photographs of daily ordinary life, and landscape that Dirgha Man took, give us a rare glimpse of life at that time. The proliferation of images from this era is unprecedented and many examples are included in the book.

When Dirgha Man retired around the mid 1940s, his son Ganesh Man took over his position as a court photographer. He only worked for a few years with the Ranas until 1951 when the rule ended. He then worked for USAID and UNESCO extensively documenting development work, landscape and monuments throughout Nepal. By the time Ganesh Man opened a photo studio in the 70s, photography was no longer used only by the elite. Photography was a modern medium and people expressed and captured their own ideas of what it meant to be modern citizens.

Dirgha Man and Ganesh Man’s photographs captured the shift in the use of photography. They show how it progressed from the restrictive Rana period, when access to the outside world and photography was limited to the privileged few, to the post-Rana era when photography took on a different shape in the private and public sphere. It demonstrates how the state, international agencies and the public adopted photography to tell a national story of progress. These images document the shift from portraits and political pomp, to photographs of development, the land and the people.

The Chitrakar family history is intertwined with Nepal’s political history. As painters, photographers, and cameramen through the generations, we have made important contributions. Keeping within the tradition of artists, the needs of the state, and changes in technology, my family moved from painting to photography and then to videography. My father worked as a cameraman for the national television station and is also a third-generation photographer. My brother follows in his forefathers’ footsteps as a fourth-generation photographer. Similar to the photographers preserving a heritage, I, as an art historian, continue my family’s tradition not as a visual documentarian but as a documentor of the culture around photographs. I see this as a continuing legacy. As serendipity would have it, Digha Man and Prime Minister Chandra share a common descendent – my son Samay. I’m sure the irony would not have been lost on either men had they known this future all those years ago when one was taking the photograph of the other!

After countless hours of selecting photographs out of more than 5000, the images in the book give a good glimpse of our entire collection. It goes beyond the opulence of court life, glamorous clothes and grandeur of the palaces, and reveals the non-court life as a part of history. These images span about 100 years exploring all aspects of life: from rulers to common people, official functions and public ceremonies to everyday culture and religious heritage. Each photograph has an accompanying text identifying people, places, and events. However, dating the photographs has been a challenge, particularly those of landscapes. In cases where the dates of the event cannot be corroborated, a date range is mentioned rather than a specific date. After much research I have tried my best to include as much information as I could find about each image. My hope with the book is that the unknown subjects in the photos can be identified by their contemporary relatives so we can preserve their stories too. This collection is not only my family’s heritage but also an account of Nepal’s history. I hope that Nepal Remembered will give these photographs a new life and inspire further research.

– Cristeena Chitrakar